(Bloomberg) --Let’s say you and I are neighbors. You’re an emergency room doctor, and I don’t work, thanks to a pile of money my grandparents left me.

You spend your days and nights stitching up gunshot wounds and helping children survive asthma attacks. I’ve gotten really good at World of Warcraft, winning EBay auctions, and frying shishito peppers to just the right crispiness.

Let’s also say we both report $300,000 in income to the Internal Revenue Service this year. Who pays more in taxes?

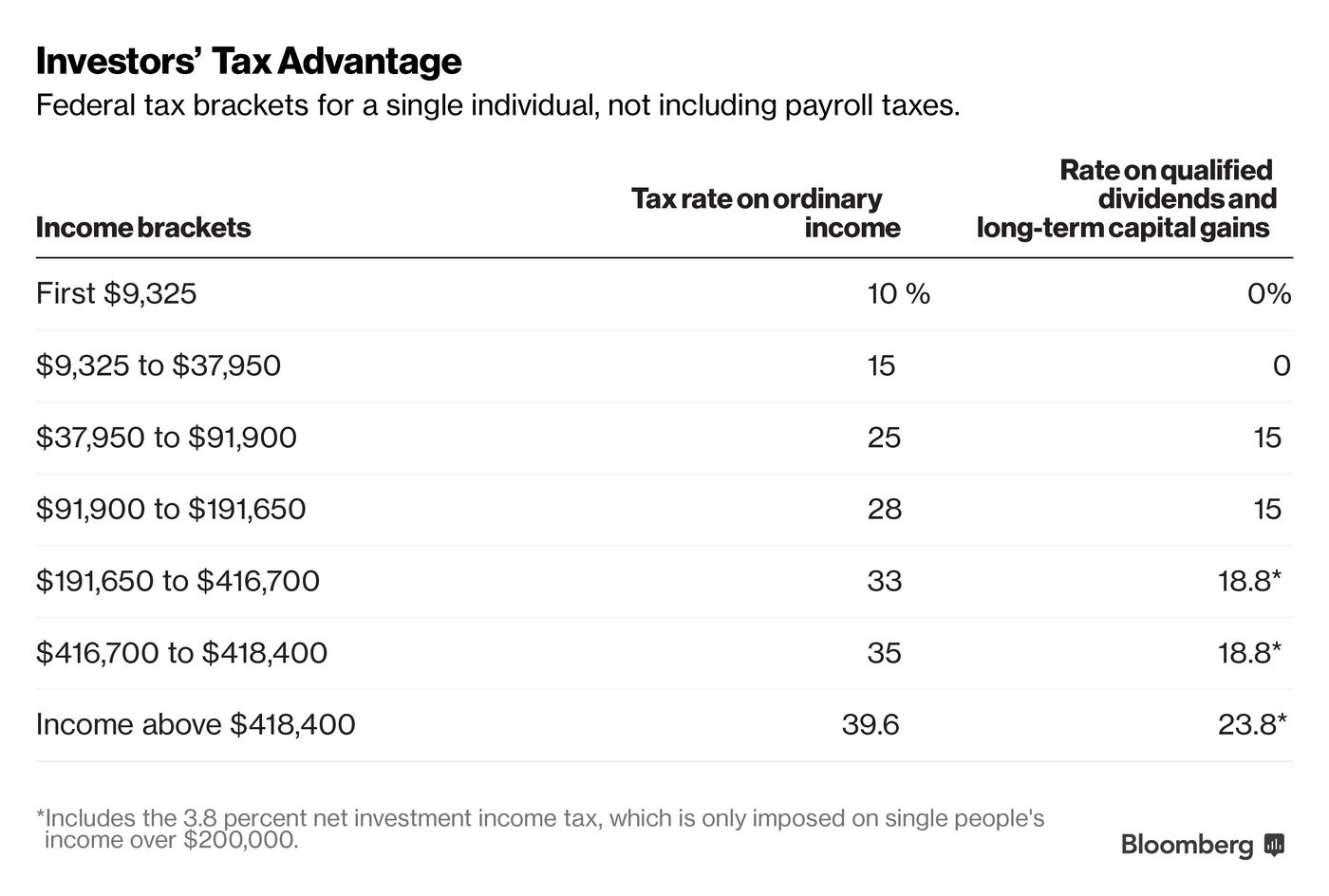

You do, by a lot. You owe the IRS about $38,500 more, assuming each of us pays the maximum with no special deductions. I also have more flexibility to lower my burden with tax planning strategies and other tricks, and I get to skip about $24,000 in payroll taxes that you and your employer must fork over each year.

This isn’t some quirk of the U.S. tax code. Politicians have intentionally set tax rates on wages much higher than those on long-term investment returns. The U.S. has a progressive tax system in the sense that well-paid workers sacrifice much more than poor workers on their “ordinary income.” But Americans with so-called unearned income—qualified dividends and long-term capital gains—get a break. A billionaire investor can pay about the same marginal rate as a $40,000-a-year worker, a fact Warren Buffett has famously lamented.

The last time Congress passed comprehensive tax reform, in 1986, it eliminated the gap between workers’ and investors’ taxes. Their rates didn’t start diverging again until the early ’90s, when Congresses controlled by Democrats boosted taxes on wealthy Americans’ wages more than on their investments. Republican-controlled Congresses widened the gap further by slashing rates on rich investors in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

A 1986-style rebalancing is unlikely to happen this fall, however, as President Trump and his fellow Republicans in Congress attempt to tackle tax reform. The gap may even widen further.

A key goal is to “simplify the [tax] code so much that you can fill out your taxes on a postcard,” House Speaker Paul Ryan said on CNN on Aug. 21. While other details of proposed tax reform remain fuzzy, Ryan and other Republicans have been promoting a draft of that postcard on social media.

The first line asks filers to write down their previous year’s wages. For you—the ER doctor in the fictional scenario above—that would be $300,000. The second line asks filers to add just half of their investment income. For me, that would be $150,000.

The form’s simplicity makes its priorities clear: No matter what rates are applied or which deductions or credits are allowed, a worker would end up paying twice as much in taxes as an investor with the same income.

Americans in the top 1 percent, and especially the top 0.1 percent, have seen their wealth and income multiply in recent decades as the rest of the country’s share of the economic pie shrank. Since 2000, a recent study found, the top 1 percent have made those gains almost entirely on income from capital, especially corporate stock—not on labor income. One reason may be the financial options of the wealthy: Business owners can lower their tax bills by paying themselves in dividends rather than in salary, for example.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Treasury is expected to run a 2017 deficit of $693 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s latest estimate, some $108 billion more than in the 2016 fiscal year. As baby boomers retire and health-care costs rise over the next few decades, the government’s fiscal situation is expected to worsen.

The argument in favor of lower taxes on investors—and on corporations, another GOP priority—is an economic one.

“We want a tax code built for growth,” Speaker Ryan said. “We want a tax code that raises wages, keeps American companies in America, gives us faster economic growth.”

Trump, Ryan, and other Republicans in Congress are wrangling over a variety of competing goals for reform. The most aspirational is a tectonic simplification of the tax code that really would allow everyone to file using a postcard. But more realistic legislative targets are lowering tax rates on individuals and corporations as well as eliminating the estate tax and alternative minimum tax. They may also try again to kill the Affordable Care Act taxes—including those on all that investment income raked in by the wealthy.

By taxing investors less, some economists argue, you give taxpayers more of an incentive to save. The more savings in the economy, the more capital that companies and entrepreneurs can invest in ways that expand the economy and make workers more productive. Everyone, including workers, wins, according to this theory.

But there are potential negative consequences to such a policy. By lowering taxes on investors, you shift more of the tax burden to well-paid workers. This may give highly skilled and creative people a disincentive to work hard or improve their skills so they can earn more money, while also giving children of wealthy parents another reason not to work at all.

The most famous economic boom in U.S. history occurred when top tax rates on dividends were as much as 90 percent

And why do people need a special tax break to motivate them to save? Aren’t there already powerful incentives to be thrifty? Invested well, money can compound and multiply over time in extraordinary ways. Wealth also provides security, status, and power—including the means to make campaign donations to politicians.

Economists have answers to some of these questions, if you trust their theoretical models. An often-cited 1999 Federal Reserve study used dozens of algebraic equations to divine the ideally efficient tax system. It concluded that the optimal tax rate on investment income is “zero.” That’s contradicted, however, by another theoretical model, published in the American Economic Review in 2009, that found the best rate is more like 36 percent.

Nevertheless, given economic theory’s recent track record, it may be better to stick to real-world data.

There’s evidence, for example, that investors feel influenced by taxes far more than workers do. If you worry about tax incentives distorting the economy, taxes on workers should worry you less: People tend to keep going to work everyday no matter what. Most economists agree that men in the prime of their careers “are not particularly responsive to the tax rate,” said University of Michigan economics professor Joel Slemrod. Similarly situated women are only “responsive at the margins.”

Investors, by contrast, are much more sensitive—at least in the short term. It’s happening now: If taxes on the wealthy drop next year, as many tax planners assume they will, then rich people have an incentive to wait until 2018 to recognize investment income by selling stocks or businesses they own. And that seems to be what they’re doing; revenue to the U.S. Treasury dipped this year even as the economy remains strong.

In other words, governments should tax workers more because they can get away with it. However unfair it might be, the disparity doesn’t affect economic behavior as much.

“Taxing investors less is really not what the U.S. needs now”

There’s a big flaw, though, in the argument that lower taxes on the rich stimulate longer-term investment, and thus jobs, famously labeled as “trickle-down economics.” While tax rates might affect the timing of some investor decisions in the medium term, it’s much harder to see how they affect long-term behavior. No matter the tax rate, investors ultimately look for opportunities to get richer.

“There is little empirical evidence showing that taxing investors less stimulates savings and growth,” said Emmanuel Saez, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley.

Supply-side economists disagree, and can point to tax cuts in the 1980s that seemed to spur the U.S. and U.K. economies. But there’s little evidence of a relationship between economic growth and investment taxes over the long term.

The most famous economic boom in U.S. history, right after World War II, occurred when the top rates on dividends were between 70 and 90 percent. Rapid growth also followed tax hikes on wealthy investors in the late 1980s and early ’90s. And more than a decade later, the Great Recession swamped any conceivable benefits from then-President George W. Bush’s tax cuts, which dropped the top rate on dividends by half.

Democrats, including former President Barack Obama, have proposed higher taxes on investment income. For example, the so-called Buffett Rule would have imposed a minimum rate of 30 percent on all taxpayers with income of $1 million or more, no matter where the money came from. That didn’t pass, but Congress did bump up the rate on capital gains and dividends from 15 percent to 20 percent. And it imposed the net investment income tax, or NIIT, a 3.8 percent levy on wealthy investors, to help fund the Affordable Care Act.

Efforts to kill the NIIT stalled in the Senate along with bids to repeal the ACA, but some House Republicans aren’t giving up. The NIIT is “incredibly anti-growth,” House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady, a Texas Republican, said in July. Last month he acknowledged, however, that getting a repeal bill past the Senate could be “a challenge.” The Tax Foundation, a conservative think tank that relies on its own models, estimates repealing the NIIT would boost the U.S. economy by 0.7 percent over the next 10 years.

Even if you believe low investment taxes can spur economic growth, you might question whether lowering taxes further will have much of an effect these days. The vast majority of wealth held by the middle class is held in homes and retirement accounts. Tapping a retirement account never triggers a capital gains tax, and selling a home only does if the gain is more than $250,000 for a single person and $500,000 for a couple. If you have less than $38,000 in investment income, you already pay a tax rate of zero.

Eliminating the NIIT or lowering other investment taxes is then, at its core, about stimulating the economy by getting the wealthy to save and invest more. But the rich are already saving—a lot. Saez and his Berkeley colleague Gabriel Zucman calculate the top 1 percent of America by wealth have consistently saved more than 30 percent of their income since at least the 1970s.

Meanwhile, the bottom 99 percent has been saving less and less—a factor contributing to growing inequality along with stagnant middle-class wages and rising debt levels.

While retailers complain there’s not enough consumer spending, trillions of dollars are sitting in investment accounts. Banks have a glut of deposits, stock market valuations are high, corporations are flush with cash, and prominent investors have more money than they know what to do with. Buffett’s cash pile is just shy of $100 billion. The median U.S. worker from age 55 to 64, however, has just $15,000 saved in retirement accounts, according to a recent study by New School for Social Research’s Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis.

“Taxing investors less is really not what the U.S. needs now,” Saez said. “Instead, we should focus on trying to rebuild middle-class wealth” by encouraging families to save for retirement and pay down mortgages.

Never mind the arguments over what’s best for the economy, though. There’s that ultimate American question about taxation we’re forgetting: What’s fair?

It’s not right, some conservatives argue, to tax investments at all. It’s “double taxation” to take a bite out of money flowing from assets that were taxed when first earned. (Technically, it’s dividends and gains that are taxed, not the original amount that’s saved, but the IRS makes no provision for inflation.)

Taxing workers more than investors is fair, conservatives also argue, because investors and workers are really the same people at different stages of their lives. When you’re young, you save and pay high tax rates on your wages. When you’re old, you get to enjoy the lightly taxed proceeds of that invested income.

The wrench in these arguments is the massive jump in inherited American wealth—driven by rising income inequality and loose tax laws. In practice, the person who successfully accumulates assets is often not the person who spends them. Affluent retirees are increasingly reluctant to even touch their nest eggs. A huge and disproportionate share of the nation’s largest fortunes is in the hands of people in their 80s and 90s. And the estate tax, already very easy for the wealthy to avoid, is targeted for elimination by the Trump administration.

As a result, an unprecedented amount of wealth may soon be inherited. The generation on the receiving end of this familial largesse will get a tax break every time they cash in on the fruits of others’ labor.

Yes, many of these lucky heirs and heiresses go to work anyway, or contribute in other ways. Still, it’s hard to argue that productive members of society—people like our ER doctor—should pay twice as much in taxes as people who sit around playing video games. But that’s the choice that underlies America’s tax code—and one that will figure in the debate over how, or whether, to rewrite it.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at [email protected]