By Komal Sri-Kumar

(Bloomberg Prophets) --This month marks the 10th anniversary of the beginning of the global financial crisis that set off the Great Recession. What the then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke had characterized as a mere “$50 billion problem” morphed into a plunge in equity values with investors losing trillions of dollars, and a recession that caused unemployment to peak at 10 percent in October 2009.

What have we learned a decade later? We found that as the Fed increased its holdings of bonds to $4.5 trillion -- more than five times the level at the onset of the financial crisis -- the additional liquidity boosted the financial markets to new heights. The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, which bottomed out at an intraday low of 667 in March 2009, now trades at about 2,445. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, which some analysts had repeatedly predicted would surge to as much as 4 percent, is still well below the 2.5 percent mark. Equity multiples have risen with stock prices. For example, the S&P 500, which traded in November 2008 at just 11 times its trailing 12-month earnings, now trades at about 21 times.

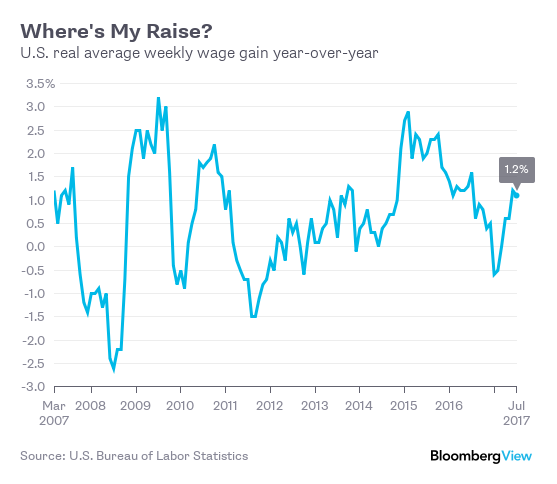

The euphoria in the equities market isn't matched by the real economy. Gross domestic product growth has been lackluster -- very different from the strong recovery that followed the 1981-82 recession. Labor force participation rates are below pre-recession levels of 2007 rather than increasing as they have in past recoveries. The weakness of the recovery is especially evident in real wages. After falling sharply during the financial crisis, the pickup in real average weekly earnings has been weaker than normal, rising just 1.2 percent year over year.

The marked divergence between the performance of financial markets and the broader economy provides a window into the impact of economic and regulatory policies. The response to the economic crisis since 2008 has been focused on monetary easing to the almost total exclusion of tax reform, structural adjustments and measures to deregulate. Investors used the liquidity supplied by the Fed to bet on increases in equity prices and falling bond yields, while households sought out riskier assets such as high-yield bonds to escape the zero rates on bank deposits. There was little to aid the real economy.

Now, with the elevated values of financial assets, it may be time to pay the piper. The Fed appears to recognize its role in the speculative run-up in financial asset prices based on Chair Janet Yellen’s reference in June to “somewhat rich” valuations. The Fed has increased interest rates four times since December 2015, three of them since last December. Now there is a plan afoot to gradually pare the Fed’s $4.5 trillion balance sheet by not reinvesting some of the maturing bonds. This process could begin as early as October.

With the shift in Fed policy, investors face a dilemma. Although surging corporate earnings this year have provided support for the continued rise in share prices, a steady tightening of monetary policy would be a headwind. And if other measures -- on the fiscal, structural and regulatory fronts -- don't offset the negative impact of a restrictive monetary policy, those lofty equities valuations may no longer be justifiable, touching off a sharp correction. That, in turn, could push the economy into recession, once again increasing unemployment.

President Donald Trump is proud of the stock-market rally during the first few months of his administration, and he also wants to push GDP growth to 3 percent or more. For the rally to continue and for him to achieve the growth objective, his administration needs to focus on two major areas.

The first is deregulation. Although markets need regulations to function, in excess they get in the way of economic efficiency. Unfortunately, the Obama administration added thousands of pages of rules governing even simple transactions toward the end of its term. The Trump administration has reversed some of the more burdensome rules, though there is still a way to go.

Deregulation would boost share prices of companies in energy and finance. For example, allowing more drilling on federal land will increase oil and gas production and create jobs. The financial sector could also continue to rally with well-designed rule changes. Although some of the post-financial crisis regulations to limit leverage were clearly justified, the pendulum has swung too far the other way, limiting bank lending to the private sector.

The second is taxes. Lowering corporate taxes to encourage investment spending, and offering employment tax credits to promote hiring, are other areas to focus on.

As the Fed reduces its asset holdings and keeps hiking rates, whether the rally persists will depend on the measures the administration does, or doesn't, implement in coming months.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Komal Sri-Kumar is the president and founder of Sri-Kumar Global Strategies, and the former chief global strategist of Trust Company of the West.

To contact the author of this story: Komal Sri-Kumar at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view