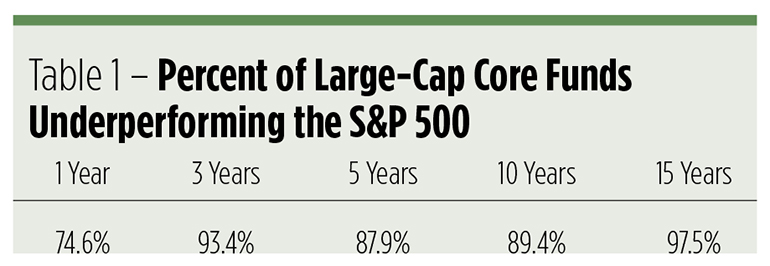

Alpha is hard to come by. Correction: Positive alpha is rare, negative alpha is plentiful. Just look at the latest SPIVA, the S&P Index Versus Active Scorecard. Over the past decade, barely 11 percent of large-cap core mutual funds beat the S&P 500 Index. Now, many investors and financial advisors equate outperformance with alpha but that isn’t necessarily so. Alpha is actually the return earned over that of a fund’s beta-adjusted benchmark — it’s a higher bar.

Let’s say a few funds earn 2 percent more than their common benchmark. One is more volatile than the market and exhibits a beta of 1.15. The other is less volatile and posts a .90 coefficient. The high-beta fund’s alpha will be lower than that of the less volatile portfolio. In fact, the high-beta fund’s alpha reading may actually be negative. Volatility is the handicap in the alpha derby.

Alpha is what you earn — above (or below) the market return — for investing idiosyncratically. Timing and security selection are the means by which active managers attempt to produce market-beating returns and, hopefully, alpha. Alpha is desirable because it’s a portfolio diversifier. If you can consistently snag alpha, you’re less vulnerable to the market’s twists and turns.

With that in mind, you might think that equity investors had an embarrassment of riches over the past eight years. A relentless bull market has certainly bestowed ample opportunities to play for beta. With an average annual gain of 17 percent in the S&P 500, the second-longest bull market of the post-war era has certainly been a boon for passive investors. We have to wonder, though, if the bull market made it easier or harder for investors to put a chalk mark on the positive side of the alpha ledger. How did actively managed portfolios fare?

To answer that question, we tapped the Morningstar database for large-cap core funds currently credited with positive alpha. We restricted our universe to funds that can be bought without brokerage transaction fees, but stretched the alpha requirement from the three-year Morningstar threshold back to the bull market’s inception in March 2009. We found only seven portfolios that met our additional criterion of self-identified benchmarking to the S&P 500 — little more than two percent of our universe.

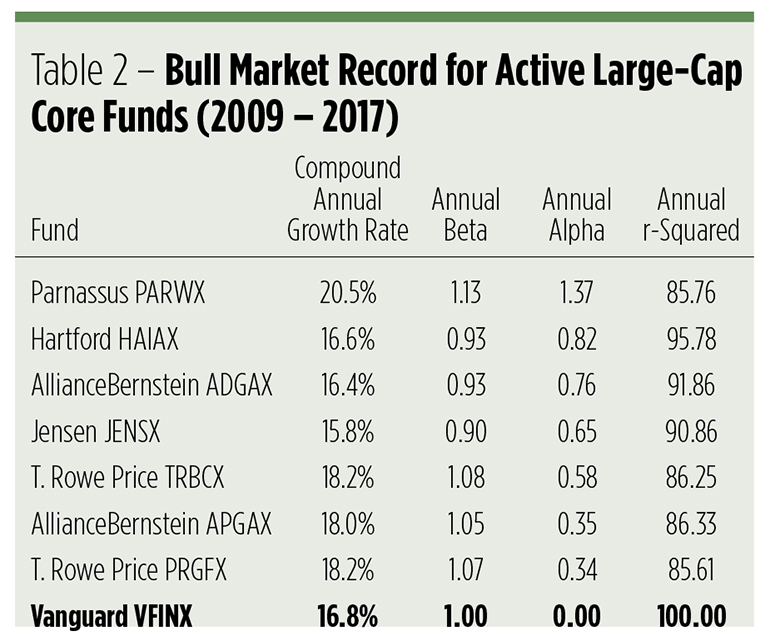

When you look at Table 2, you’ll notice that only four funds produced annualized returns higher than the Vanguard 500 Index Fund (OTC: VFINX), our investable proxy for the large-cap core market. Even so, those three “laggards” pulled out positive alpha. Remember, outsized gains don’t necessarily signal positive alpha; neither does underperformance correlate to negative alpha. You’ve got to do the math.

You’ll also see r-squared coefficients displayed for each fund. This metric reveals the degree to which movements in the benchmark explain each fund’s trajectory. Think of it as a more granular measure of correlation. An r-squared of 100 means there’s a perfect fit with VFINX; any fund with a reading close to 100 is essentially an index tracker. That’s an important consideration. Beta (at least a 1.00 beta) is cheap. After all, VFINX costs only 14 basis points (0.14 percent) to hold annually. You’d expect to pay up for alpha, and so you do. The average r-squared coefficient for the funds in our table is 89 and the mean expense ratio is 90 basis points.

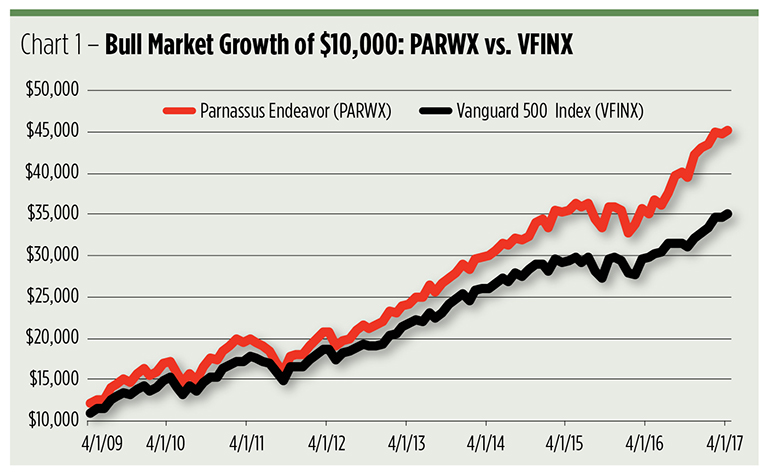

At the top of the table is the Parnassus Endeavor Fund (OTC: PARWX), a portfolio that invests in companies with strong competitive advantages and high ESG (environmental, social and governance) values.

As you can see, the Endeavor fund stands out because of its outsized returns as well as its significantly higher beta and alpha coefficients. The fund’s r-squared value, on the other hand, is one of the table’s lowest.

Even so, Endeavor’s r-squared is north of 85, implying that just 14 percent of its price movement has been idiosyncratic. That doesn’t mean, however, that 14 percent of the fund’s portfolio is actively managed.

Active Share and Cost

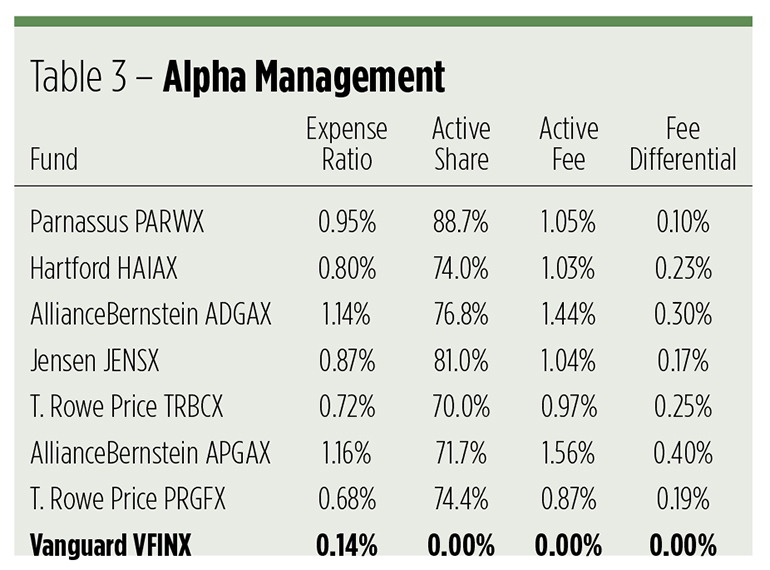

If you look into the Endeavor fund’s portfolio and compare its holdings with that of the S&P 500, you’ll see little overlap. According the Active Share methodology, devised by Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto, just 11 percent of PARWX’s portfolio weight is held in common with VFINX. It’s that portion that nominally provides market beta but no alpha. If we could unbundle the risk factors and costs, we’d expect to pay just 14 basis points for this share of the portfolio.

Holistically, 89 percent of the PARWX portfolio is the active share and 11 percent is the benchmark. The sizable active share gives this fund a lot of maneuvering room to earn its alpha. In fact, the Endeavor fund has the highest active share of all the portfolios examined here (see Table 3).

An actively managed portfolio must earn the benchmark return plus the added cost of the active share to justify an investment. That said, funds with smaller active shares have to work harder to generate alpha. Take, for example, the T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth Fund (OTC: TRBCX) which has a 30 percent overlap with the S&P 500. Its active share — just four-fifths the size of Endeavor’s — must still generate enough gain to overcome its cost as well as that for the passive return.

So what’s the actual cost of active management? Cremers and Petajisto supply the algebra that allows us to come up with the costs shown in Table 3.

As you can see, the Parnassus Endeavor Fund isn’t cheap. At 95 basis points, its expense ratio, while not the priciest, is still above average. But, because of its high active share and the skill of its managers, the incremental cost for alpha is modest — just 10 basis points more than the fund’s stated expense. Investors in the T. Rowe Price Blue Chip Growth Fund, in contrast, pay 25 basis points above the published rate for active management.

By any measure, the Parnassus Endeavor Fund has been, pound-for-pound, the most cost-efficient alpha engine among large-cap core portfolios. Over the past eight years, it’s cranked out 1.37 points of alpha at an annual cost of 1.05 points — a 1.3-to-1 ratio. The AllianceBernstein Large-Cap Growth Fund (OTC: APGAX), with a 0.2-to-1 ratio, has been the least efficient portfolio.

Takeaways

In light of the foregoing analysis, a few points stand out. First, a fund’s stated expense ratio doesn’t convey its true cost — unless it’s explicitly an index tracker. Second, a fund with a high active fee can still be an efficient alpha producer.

Let’s put all this in perspective, though. We’ve looked back at the behavior of just one segment of active mutual funds since the inception of the bull market. A question remains: are these the large-cap core funds to own for the rest of the bull run? Perhaps, but no one can know for sure. Neither can we know how long a run that might be.

Still, Sam Stovall, chief equity strategist at CFRA offers this trenchant observation: "Bull markets don’t die of old age, they die of fright. And what they are most afraid of is recession."

Currently, recession expectations are low though they have been on an upward track this year. ‘Nuf said.