By John Gittelsohn

(Bloomberg) --Scott Minerd wadded up another piece of paper and looked out at the Pacific Ocean from his Santa Monica, Calif., office. He needed a better blueprint for his organization—a foundation for his investing process that could support consistent performance—and his ballpoint drawings still weren’t right. So Minerd kept sketching: boxes, arrows, words, whatever came to mind. When he found himself swimming in “spaghetti” doodles again, he’d ball up the paper and start anew.

Minerd had dealt in bonds, structured securities, currencies, and derivatives during highflying stints at Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and Credit Suisse First Boston in the 1980s and ’90s, running desks for bosses such as John Mack and Bob Diamond; the work burned him out at the ripe old age of 37. “I walked away from extremely large offers on Wall Street,” he says today. “I realized this wasn’t a dress rehearsal for life, this was it.”

He’d been away from the business for two years when Mark Walter, a former client who ran the investment firm Liberty Hampshire, came to lure him out of early retirement in 1998. Minerd had two conditions: He would retain his autonomy and remain in California, his home since walking away from trading. Soon, Liberty merged with the family office of 19th century mining baron Meyer Guggenheim’s heirs, transforming the little-known investment house into Guggenheim Partners, a boutique asset manager.

By 2002, Minerd realized he needed to be systematic to make Guggenheim a force, hence his ballpoint attempts at a new blueprint. Eventually, a concept from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations—about how the division of labor leads to higher productivity—popped into his head. “The idea is if you segregate duties, you get greater efficiency and better results,” Minerd says. Inspired, he drew four boxes inside a wheel. For Minerd, each box represented a specific part of the investing process: macroeconomic analysis, security selection, portfolio construction, and portfolio management. The simple structure let “the data talk,” he immediately realized. Managing money could be a coolheaded, calculated process with scalable, replicable results, “not me just sitting in a room saying, ‘We need to do mortgage-backed securities.’ ”

It’s common for money managers to break investing into specialties, but Guggenheim, which today oversees an impressive $260 billion, shows how structure can drive results. “Scott is methodical and patient,” says Walter, the firm’s chief executive officer. “He was a prime architect of Guggenheim Partners’ disciplined investment process—a process we have inculcated throughout our asset management business.”

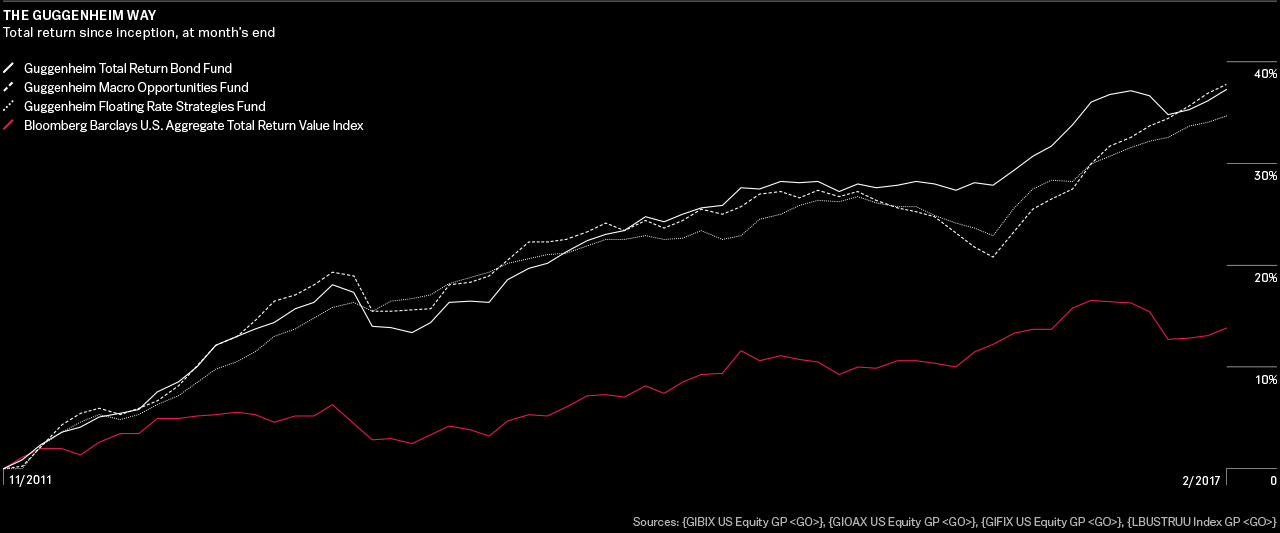

In fixed income, in particular, Minerd has racked up a prolonged hot streak. According to data compiled by Bloomberg, the $5.7 billion flagship Guggenheim Total Return Bond Fund has beaten 97 percent of its peers over the past five years, chalking up a better record than similar funds headed by fixed-income gurus such as Jeffrey Gundlach, Bill Gross, and Dan Fuss. Assets doubled over the past 12 months, as more investors discovered the fund, which celebrated its five-year anniversary in November.

“I let the data talk to me and try to keep the emotion out of it,” says the 58-year-old Minerd, who’s barrel-chested from years of bodybuilding. His $5 billion Guggenheim Macro Opportunities Fund—a credit-focused fund that invests in a range of equities, commodities, and alternative investments, as well as bonds—has returned an average 5.6 percent over the five-year stretch, beating 95 percent of its peers. The $3.5 billion Guggenheim Floating Rate Strategies Fund, which focuses on bank loans and other adjustable-rate debt, has bested 96 percent of its peers over five years. About 57 percent of Guggenheim’s assets are separate accounts for insurance companies, endowments, and other institutional investors who don’t publicly disclose their results.

“I have never met anyone who’s a better judge of credit or structurer of transactions than Scott Minerd,” says Jim Dunn, CEO of Verger Capital Management, which oversees $1.5 billion for nonprofits, including Wake Forest University’s endowment. “We call him the bond savant.”

A built-in benefit of Guggenheim’s structure, Minerd says, is a system that slows decision-making, preventing traders and portfolio managers from making hair-trigger moves based on fear, greed, or personal biases. “If you want to do emotional investing and call all the shots, Guggenheim is not the place for you to work,” he says. “If you don’t allow one person to make all the decisions, it really slows the process, resulting in better decisions.”

Slow decision-making dovetails with research by Daniel Kahneman, a behavioral economist, 2002 Nobel Prize winner, and subject of Michael Lewis’s 2016 book The Undoing Project. In 2006, Kahneman helped Guggenheim develop and trademark individualized profiles for high-net-worth clients called “Riskometry,” which matches return expectations and risk appetite. It provides a framework for thinking slow in the fast and furious field of investing, an approach Minerd says has paid dividends in bear and bull markets.

Over breakfast at an outdoor cafe in Santa Monica, Minerd recalls panicky clients phoning him during the 2008 financial crisis. Sell everything, they’d say. It was classic fear-driven decision-making, he says. To calm the investors, he’d retrieve their Riskometry assessments and ask two questions: Had performance met or exceeded expectations in the event of a market downturn? And had the investments stayed within risk guidelines? In every case, Minerd says, the answers were “yes.” “We’re really only left with one conclusion,” he would tell his jittery customers. “We should increase your risk.”

Minerd pauses to let the thought sink in. His pointy-eared rescue dog, Grace, stretches at his feet under the cafe table. “Virtually every client agreed to increase risk,” he continues. “The financial crisis was the best thing that ever happened to us.”

Minerd, the son of an insurance salesman, grew up in southwestern Pennsylvania on land his family settled before the Revolutionary War. He quit high school a year early to follow a girlfriend to Philadelphia, where he persuaded the University of Pennsylvania to allow him to take courses at the Wharton School. After earning a degree in economics from Penn in 1980, he took classes at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and then worked as an accountant for Price Waterhouse. He switched to investing, which paid better, and started climbing Wall Street’s ranks for the better part of a decade. “He’s a hard-charging guy, and he doesn’t suffer fools,” says Mack, who supervised Minerd at Morgan Stanley. “That’s what you need in this business.”

In 1992, Minerd generated a big win for Morgan Stanley by trading Swedish bonds after the country raised its interest rate to 500 percent to defend its currency. The next year he orchestrated a debt restructuring for Italy that helped stave off a bailout by the International Monetary Fund. He left Morgan Stanley for CSFB in 1994, running the fixed-income credit trading group under Diamond, who two years later jumped to Barclays Plc. Minerd was shuttling between New York, London, and European capitals, facing second-guessers and corporate intrigue. He followed Diamond out the door, only in a different direction—west to California for the sun, the food, and the fitness.

“People thought I was crazy when I moved out here,” Minerd later says over lunch at the Firehouse, a Venice Beach restaurant frequented by bodybuilders. He bought a waterfront home and devoted himself to lifting weights at Gold’s Gym in Venice, an institution for bodybuilders such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, but eventually changed venues because people were constantly interrupting to ask about money management. “I couldn’t get in a good workout,” he says.

At his peak, the 300-pound Minerd could bench-press 495 pounds 20 times and even competed in the Super Heavyweight and over-40 divisions at Los Angeles bodybuilding championships. “I don’t like to do things halfway,” he says, tucking into a Bob Bowl, a 12-ounce steak with sautéed red peppers and onions over rice. “Bodybuilding is 24/7,” he says. “It’s everything that goes into your mouth. It’s if you get enough sleep. It’s how you manage your stress.” Minerd remains disciplined in the gym—hence his Popeye arms. He tries to clock a two-hour workout five days a week in the window between the time markets close in New York and open in Asia.

“If I was ever going to say ‘no’ to him, it would be by phone,” jokes Guggenheim Executive Chairman Alan Schwartz about Minerd looking so physically intimidating. “But I can tell you that his heart and brain are bigger than his body.”

Minerd presided over a December meeting of his macro team in Guggenheim’s Manhattan office in a glass-walled conference room overlooking Grand Central Terminal. Maria Giraldo, a research analyst, explained how his demands for data spurred her to reexamine her biases about the risks of credit investing. “I have this instinctively bearish view based on the length of the business cycle,” she says.

At Minerd’s urging, Giraldo read reports written before the 2008 financial crisis in search of early trouble signs, such as deals being pulled and credit spreads widening. The red flags that showed up a decade ago weren’t happening in late 2016. By contrast, recent company earnings were better than expected, leading Giraldo to revise her forecasts for the current credit cycle to continue at least until 2019. “It could push it out even further,” she says.

Minerd concedes that his investing process can test his clients’ patience. “I tend to be early to sell, and I tend to be early to buy,” he says. “If you’re going to be early, you tend to have periods of underperformance.” In late 2014 he began selling most of Guggenheim’s energy-related debt after his economists predicted a long-term plunge in oil prices. Then, in late 2015, he began buying collateralized loan obligations, months before oil prices hit bottom. “Going into January and February, we were having a tough time,” he says. “But those investments turned out to be a home run.”

The CLOs included mezzanine debt tranches with 15 percent yields, acquired at 40 cents on the dollar. Other money managers shun Mezz CLOs, which can fall to zero in a default, because they don’t have Guggenheim’s resources, Minerd says, including a team of in-house lawyers who pore over indentures in search of claims priorities under different stress scenarios. “You can make money two ways,” he says. “You can take risk or you can work. We do work.”

Guggenheim’s edge, according to Minerd, comes in part from handpicking debt products outside benchmarks such as the 10,000-security Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which determines allocations for passive investors. He currently likes portfolios shaped like a barbell, with low-risk, low-yield securities, such as Treasuries, at one end balanced with esoteric asset-backed securities or collateralized mortgage obligations on the other end. He looks for relative value, rotating sectors or changing asset allocations as opportunities come and go. “About 80 percent of our securities aren’t in the index,” he says, noting that the benchmark aggregate represents a minority share of more than $40 trillion in the U.S. bond market. “Why limit yourself?”

The Guggenheim Total Return Bond Fund institutional class earns five stars, the highest possible rating, based on performance, low volatility, and relatively low fees, says Todd Rosenbluth, director of fund research for CFRA. But its 14 percent stake in unrated securities as well as ABS and CLO holdings poses a downside if the fund ever faces large redemptions because of their lack of liquidity, he says. “It’s a risk that investors perhaps need to be mindful of,” Rosenbluth says. “This fund has experienced strong inflows in its life. If and when that reverses, unrated securities would be harder to sell.”

Another concern is Guggenheim’s lack of senior talent and tenure below Minerd, especially on the credit desk, according to Eric Jacobson, a Morningstar Inc. fixed-income analyst, who visited Guggenheim’s Santa Monica offices in February to begin preparing a formal review of the funds. “You’d expect to see more of that in a team that has so much responsibility for getting securities into the Total Return portfolio, for example, where they have such a huge focus on structured credit and because it’s considered such a core competency,” he says.

Guggenheim paid a $20 million fine in August 2015 to settle Securities and Exchange Commission charges that it breached its fiduciary duty by failing to disclose a $50 million loan that an unnamed executive received from a client in 2010. The SEC also found Guggenheim charged a client fees for assets that weren’t under its management and failed to enforce its code of ethics that restricted taking flights on clients’ private airplanes. Guggenheim directed questions to the SEC order and a statement issued at the time of the settlement, which said the executive implicated in the scandal left Guggenheim and that the firm had implemented more comprehensive compliance policies and procedures. “We are fully mindful of—and deeply committed to—our fiduciary responsibilities to our clients,” the statement reads. “Any failure to perform to the highest level is not acceptable.”

In December, Minerd shared a Manhattan banquet stage with then-Vice President Joe Biden and Starbucks Corp. CEO Howard Schultz as the three men each received a Robert F. Kennedy Ripple of Hope Award. Minerd was recognized for his involvement in charities, such as a Los Angeles family planning clinic, a homeless mission, and a sanctuary in Uganda for persecuted gay, lesbian, and transgender people. “I don’t feel entirely worthy,” he said in his acceptance speech. “The acts were meant to be private, motivated by conscience and love in a secret place in my soul.”

Minerd credits Scripture as his guide, and often recites passages from memory. He describes his leadership style by quoting Matthew 8:9, about the Roman centurion whose faith was a marvel to Jesus: “For I myself am a man under authority, with soldiers under me.” He recalls how his dog, a mixed breed stray, was slated to be euthanized in a shelter before her rescue. When a friend suggested naming the dog Grace, Minerd says, a letter from the Apostle Paul sprang to mind, including the passage: “For by grace you were saved, and that is not of yourself but a gift from God.” Minerd brings the dog to his office; she even joins him when he flies cross-country on the company jet. “I realized that Grace was saved by grace, a gift from God,” Minerd says as he scratches her between the ears after breakfast in Santa Monica. The two make an odd couple—the knee-high mutt and the muscular Minerd. He’s the master investor, but in some ways she’s the boss, the one who gives his life structure and purpose. “We’ve been here too long,” Minerd says, as if reading Grace’s mind. “There’s squirrels to be seen.”

The two walk out, slowly.

Gittelsohn covers investing for Bloomberg News in Los Angeles. This story appears in the April/May issue of Bloomberg Markets.

To contact the author of this story: John Gittelsohn in Los Angeles at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Joel Weber at [email protected]