(Bloomberg View) --A confluence of remarkable events is facing the issuance side of the Treasury market in the coming years. It has been heightened, at least in rhetorical terms, by words from various Fed officials, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and, not surprisingly, President Donald Trump.

The Fed is the easiest and the most immediate place to start. The last couple of weeks have enhanced the "odds" of a rate increase in March to more than 90 percent from just 38 percent. That’s ample enough to salve any Fed concerns over surprising the market and we can move on from there. A discussion about two, three or more hikes in this so-far sedate cycle is beside the point. The new thing is how the Fed handles any reduction in its balance sheet.

Any reduction is the flip side of quantitative easing, which took securities out of the market. In this cycle, there is a real threat of monetary policy not only impacting the front end but the balance of the curve via asset sales.

To the extent that happens, this cycle could change the yield curve’s behavior (bear steepening, relative to bear flattening seen in the past), and that will make forecasting the next recession dicey as we might not see an inverted curve. The balance sheet may prove to be a more permanent tool for the Fed rather than being strictly limited to this recovery.

That issue with the curve has been tremendously enhanced by the Trump administration, of course. Mnuchin said that ultra-long bonds should be taken seriously and I’d argue that there’s really no other choice. Here's how to look at Trump’s fiscal spending plans. Let’s keep it simple: $1 trillion over the next 10 years. We have that much more issuance to deal with when the budget deficit was bound to explode anyway: Well before the election, the Congressional Budget Office warned that federal debt held by the public would rise to 86 percent of gross domestic product by 2026. It’s about 76 percent today.

At the risk of provoking a call from Sean Spicer, the White House press secretary, let alone an angry tweet from the president, it’s fair to say that the numbers Trump is proposing would inflate that last figure more than 86 percent. Assumptions about growth are far too optimistic, which in turn challenges how much actual fiscal spending will occur. But this sort of musing is academic. That point is that whether the administration gets $1 trillion in new spending or zero, the deficit has to be financed. And that financing won’t be a short-lived phenomenon. That means more bonds, likely very long bonds, and thus at least relative pressure on the long end of the yield curve.

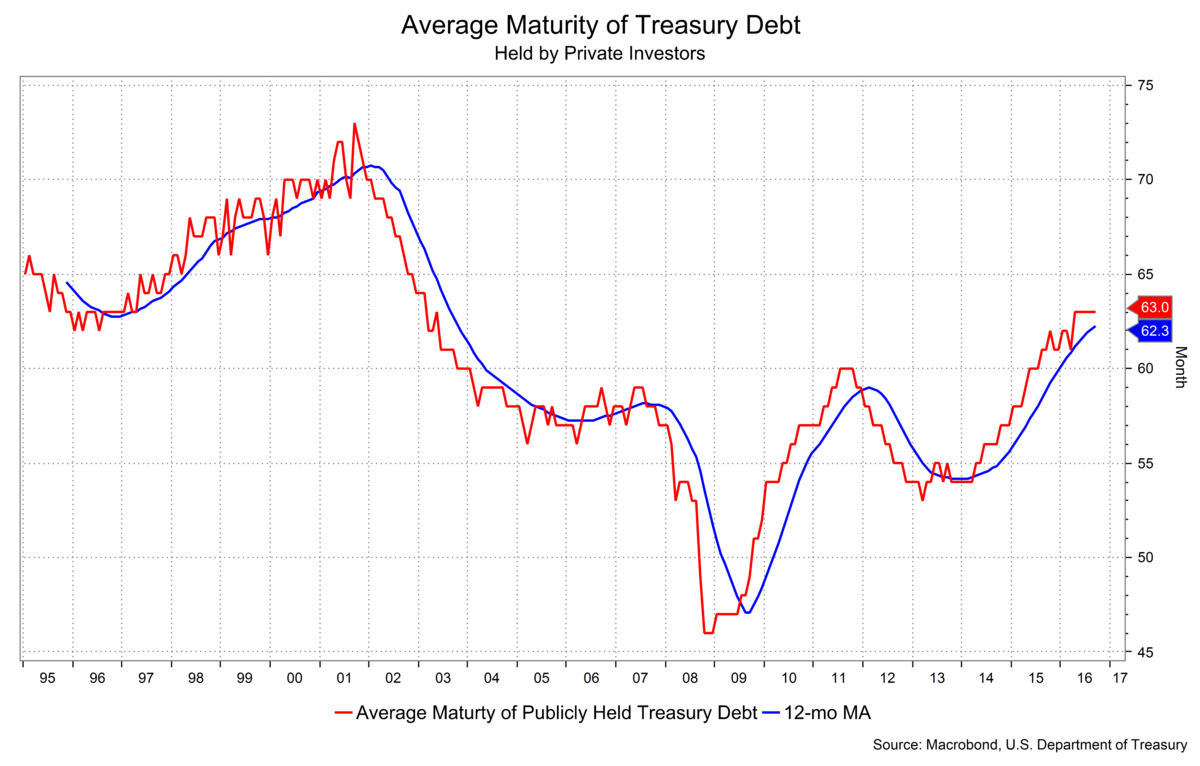

A sideshow is what it means for the maturity of outstanding Treasury debt. That’s now at 63 months, having risen steadily after QE ended, and is going to rise further. It peaked at near 73 months in 2001.

The twist I offer is what it will mean to bond-indexed portfolios -- to borrow from "Field of Dreams," “if you issue it, they’ll buy.” We’ll probably see Treasuries grow in terms of their weighting in that asset class, driving a forced need from investors managing around the benchmarks. It also means a likely increase in the incremental duration of such benchmarks and thus a need for duration. In other words, though I’m emphasizing some bearish considerations with new long issuance, that’s a lot about curve behavior. All that duration will go into the bond indexes and actually force a need to keep up with benchmarks.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence. For further information, please see: https://financialintelligence.informa.com/

This column first appeared on Bloomberg View.