By Claire Boston

(Bloomberg) --A little-noticed element of Republicans’ planned tax reform could slash the size of the U.S. corporate bond market by as much as a third, according to one bank’s estimate.

President-elect Donald Trump and congressmen from his party have both suggested cutting corporate tax rates. To pay for those reductions, the House Republicans’ plan calls for eliminating a key tax benefit associated with companies’ borrowing, namely the right to deduct interest payments from income.

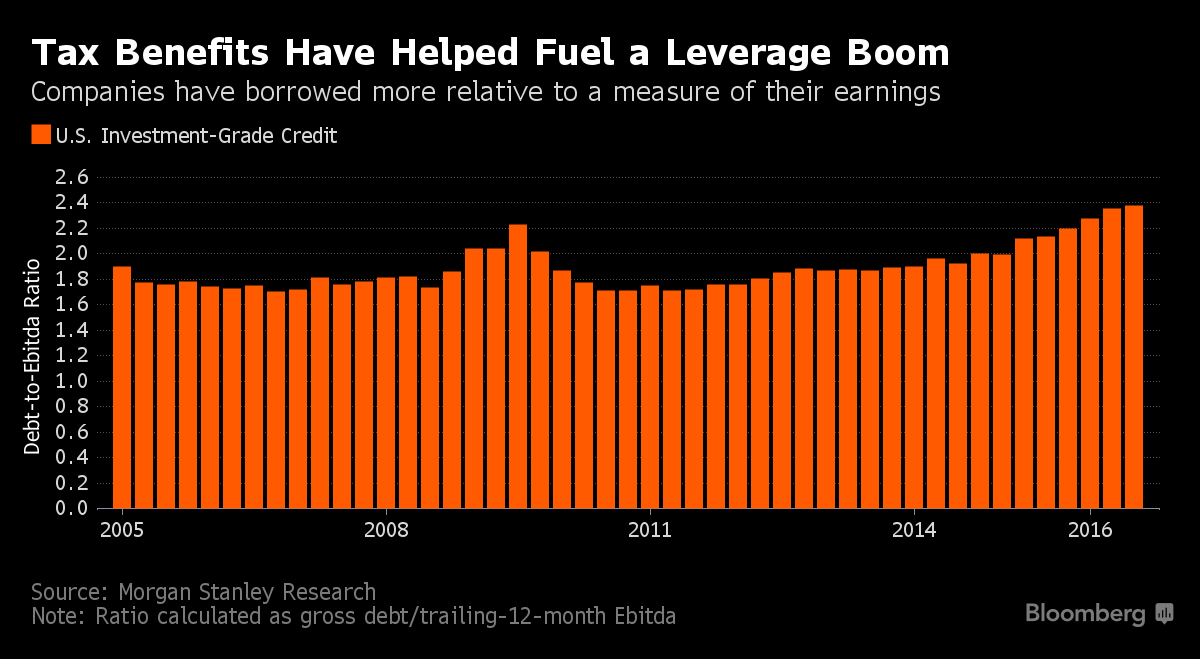

That tax deduction has helped the investment-grade corporate bond market grow to $4.87 trillion of debt outstanding. Ending that benefit could eventually slash that figure by around 30 percent, according to Bank of America Corp. analysts that considered data from the International Monetary Fund. When lawmakers eliminated deductions for consumers for most types of interest as part of sweeping tax reform in 1986, credit card borrowings plunged.

Companies have been able to deduct at least part of their interest expenses against their income for more than a century. Eliminating that benefit would likely raise about $1.1 trillion of U.S. tax over the next decade, according to the Tax Foundation, a think tank.

That would help offset another part of the House Republicans’ tax plan: companies would be allowed to deduct their expenses from capital expenditure in the year in which they occurred, instead of spreading them out over a longer period of time. Allowing that change gives businesses an incentive to invest in factories and other assets, without necessarily encouraging them to favor debt over equity financing. The Tax Foundation estimates that switching to immediate deduction will result in $2.2 trillion of lost revenue.

An Alternative

The House plan would hurt companies that fund themselves heavily with debt, such as banks and commercial real estate firms, by increasing their tax bills and decreasing their profit. Donald Trump’s plan offers an alternative solution: companies can choose to give up the interest deduction in exchange for being allowed to immediately deduct their capital expenditures.

Given Trump’s background as a commercial real estate developer and owner, he may be more inclined to support policies that are friendly to that industry, said Edward Mills, a financial policy analyst at FBR Capital Markets.

“Whenever you have someone who has a particular background in an area, you assume that they are not going to do something that would disproportionately negatively impact that industry,” Mills said. Trump’s transition team did not have an immediate comment.

However the plan ends up looking, tax reform is a priority for Trump’s administration, said Stephen Schwarzman, chief executive of Blackstone Group LP and chairman of a group of business heads that will advise Trump starting in February. He was speaking at an industry conference earlier this month.

Less Incentive

Even if lawmakers just reduce the corporate tax rate next year, companies will have less of an incentive to borrow, because with lower tax rates, a company gets less of a benefit from using deductions, Bank of America analysts wrote in a note. That alone could lower debt issuance volume.

For investment-grade companies, eliminating the deduction for interest expenses while cutting tax rates to 20 percent, the level that the House Republican plan calls for, would boost net income by an average of about 11 percent, according to Morgan Stanley estimates. For junk companies, which pay higher interest rates and therefore have higher deductions, the increase is just 2 percent.

Take the rate down to 15 percent, which was Trump’s proposal, and investment-grade companies’ income increases by an average of about 19 percent, while junk-rated companies jump 12.8 percent, Morgan Stanley said.

Results for different companies and industries will vary. For banks for example, earnings could fall by 3 percent if tax rates are cut to 20 percent and interest deductions are eliminated completely, the analysts said in a note.

Bond Underwriting

For big banks, the tax change would sting in at least one other way: debt underwriting would likely become a smaller business. Wall Street banks have generated some $10.3 billion in fees in a record year for U.S. bond sales, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, a figure that stands to slide with reduced issuance.

If companies fund their business with more equity, then stock underwriting businesses might see a surge. Companies are often reluctant to issue more common stock and dilute current shareholders, and might look to sell preferred stock instead, said Laurence Crouch, a tax attorney at Shearman & Sterling LLP.

“Preferred stock has the same benefit as debt in not diluting common shareholders,” Crouch said. Preferred dividends tend to be higher than unsecured corporate bond interest, which could offset some of the benefits to companies of having less debt.

Forecasting the precise impact of any tax code changes on businesses is difficult because there are so many unknowns, and it’s unclear how company behavior would change. For example, if tax rates are lower, projects and other capital expenditure that might previously have been unprofitable could become profitable, which could lead to a rise in investment, at least some of which would likely be financed with debt, according to Bank of America strategists.

But long term, if the tax incentive to issue bonds starts to disappear, issuance is likely to follow and outstanding debt levels will likely drop, said Hans Mikkelsen, head of high-grade credit strategy at Bank of America.

“It’s going to be very difficult to get bonds,” Mikkelsen said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Claire Boston in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at [email protected] Dan Wilchins