The latest blow in the fight for international financial transparency fell Thursday, as a new cache of leaked offshore corporate documents, this time from the Bahamas, was made public.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, alongside German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners—the same group that broke the Panama Papers scandal earlier this year—just released documents containing information about 175,000 Bahamian companies registered between 1990 and 2016. The documents are collected in a free, searchable online database alongside the Panama Papers leaks in what is quickly becoming one of the largest public databases of information on offshore entities ever collated.

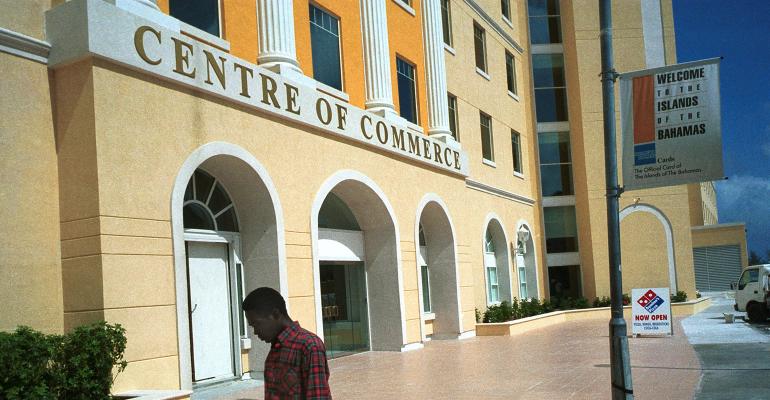

This round of leaks is somewhat less thrilling than those from Mossack Fonseca’s operations in Panama (although their name does come up) because the data uncovered is largely corporate registries, which contain only the basic components of offshore companies—name, date of creation, addresses in the Bahamas and, occasionally, the names of company directors. Indeed, much this information is available in person in Nassau, the Bahamas’ capital. But, those records are largely less complete than those in the leak and searching them incurs a $10 fee per company, which is a strong disincentive when dealing with large-scale inquiries.

Just because the information is a bit more basic than earlier leaks doesn’t mean it’s less enlightening. The simple details available reveal previously unknown, or at least underreported, links between offshore companies and prime ministers, cabinet officials, princes and, everyone’s favorite, convicted felons. The most notable name involved this time around is former EU commissioner Neelie Kroes. Additionally, and likely more importantly for authorities looking for leads as to any wrongdoing, the documents also include the names of 539 registered agents (including Mossack Fonseca) who act as corporate intermediaries between the Bahamian authorities and potential offshore customers.

“Corporate registries are incredibly important,” said Debra LaPrevotte, a former U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation special agent, when asked for comment by ICIJ. “Offshore companies are often used as intermediaries to facilitate money laundering and, frequently, the companies are only used to open bank accounts; thus the corporate registry documents, which might identify the beneficial owners, are part of the evidence.”

While it’s important to note that there’s nothing inherently illegal about being involved with an offshore company, and that most are legitimate businesses or have legitimate business reasons for existing, they are still commonly used vehicles for obfuscating financial shenanigans. And, at the very least, public officials should disclose their interests in any offshore companies in the interest of transparency and mitigating conflicts of interest.