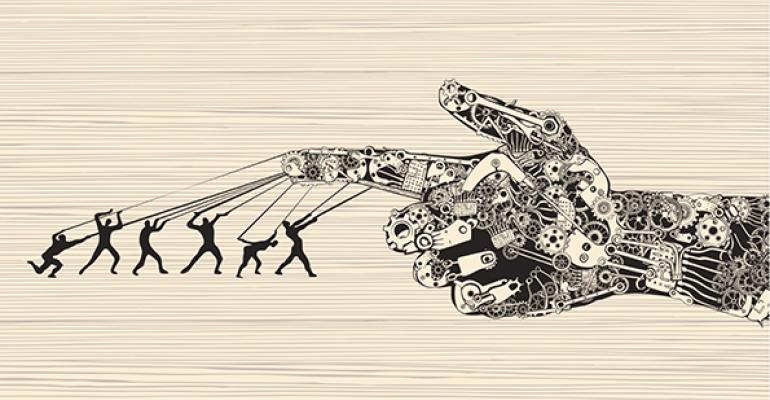

(Bloomberg) -- Machines may be taking over the world, but in at least one corner of the markets humans are beating back the robots.

Sales traders like Citigroup Inc.’s Samantha Huggins are in demand because they are proving more adept than computer programs at trading big chunks of stock, dubbed block trades. While finding a buyer or seller and completing a transaction by phone is more expensive up front, Huggins says her 18 years spent navigating the markets gives her an edge in avoiding the pitfalls of letting some software slice the trade into tiny tranches over hours or an entire day.

“Ultimately sales trading reduces their trading costs,” Huggins, a managing director at the bank, said in a conference room on Citigroup’s Canary Wharf trading floor. “If it didn’t reduce investors’ trading costs, we’d be a bunch of dinosaurs.”

So far, their niche is resurging amid an onslaught of technological evolution. In Europe, sales-trader execution of single stocks rose to about 51 percent -- the first increase this decade, according to Greenwich Associates. In the U.S., the number is 55 percent. And their ranks are swelling. Banks have been ramping up hiring of high touch sales traders in the last six to eight months, says recruitment firm Armstrong International. That’s especially notable when banks in the U.S. and across Europe have slashed tens of thousands of jobs in the last few years alone.

Not for Everyone

The bespoke service isn’t for everyone. At banks like Citigroup, the biggest clients are the ones pining for the human touch. That’s because they’re only getting bigger and so hold ever larger positions. For example, assets under management at global investment firms have been rising since the depths of the crisis, and gained 8 percent to a record $74 trillion in 2014, according to data from Boston Consulting Group.

Handling a mammoth trade presents hazards. Algorithmic trading programs try to avoid detection by drizzling out trades little by little, but traders have become adept at sniffing out those patterns and will drive prices the other way. Another risk is that news could break, whipsawing the value of the stock before the transaction is completed. Those risks are why big investors would prefer to avoid expensive mistakes and are willing to pay higher fees to make a trade in one big swoop.

So called “high touch” sales traders like Huggins specialize in those transactions, and they’re expected to know all about their customers, including what’s in their portfolios, how they like to transact and what kind of news is important to them.

Finding Counterparties

Top-tier brokers also know where to find counterparties. Global concerns such as Brexit have spooked portfolio managers into withdrawing from the market at levels not seen in more than 14 years. An algorithm can’t find them, but an astute trader might be able to.

“A sales trader can do some very creative things,” said Rob Boardman, chief executive officer for Europe of Investment Technology Group Inc., an electronic broker and dark-pool operator. The firm employs sales traders and also develops buying and selling algorithms -- dubbed algos. “An algo is not going to make a phone call to the top five holders of a stock. It’s not going to call the CIO of a large institutional investor and say, ‘Do you fancy getting out of this?”’

Small-batch, lightning-fast trading isn’t necessarily attractive to big institutional firms, says Simon Steward, head of European equity trading for Los Angeles-based Capital Group Cos., which oversees about $1.4 trillion. It uses humans for more than two-thirds of its European stock trades.

Difficult to Trade

Another concern is the boom in passive funds, which traders say dry up trade opportunities. Some index funds primarily transact in closing auctions, which can make it more difficult to trade during the rest of the day. About 20 percent of the day’s volume happens at the close in Europe, compared with 14 percent in 2009, according to data compiled by Citigroup.

“There’s a place for algos, but it’s not the only solution,” said Nick Wills, Citigroup’s Europe, Middle East and Africa head of equity platform sales. “We’re most interested in where this equilibrium goes.”

Deutsche Asset Management, which oversees $842 billion, takes pride in its electronic operation, but says about 65 percent of the firm’s trades by value still go through humans.

The firm traded more big block trades in 2014 than in the combined prior five years, said Mike Bellaro, Deutsche Asset’s head of equity trading. Block trading grew by another $15 billion last year and the company had its best trading execution ever, he said.

On a Quest

“The last five years we’ve been on a quest to bring back, if you will, block trading to the marketplace,” Bellaro said.

For customers, the commissions from a robot trader can be lower, and some estimates put it at as little as 3 basis points. A sales trader may charge commissions of 7 basis points or more. For a $250 million order, that could be a difference in commission fees of $100,000.

Another way some dealers have tried to boost profitability is by moving away from customers who don’t trade as much, Greenwich Associates says. While big clients can access premium services like research, top-performing sales traders and corporate introductions, smaller firms may be left with automated, self-service options or lower-tier dealers.

“The world is different if you’re a massive asset manager that pays the street a lot of money -- you will get very high quality sales trading coverage,” said ITG’s Boardman. “For a mid-size asset manager with $40 billion who pays the street 10 times less, whether you can really command as much quality sales-trading coverage isn’t quite so clear.”

--With assistance from Will Hadfield. To contact the reporter on this story: John Detrixhe in London at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Trista Kelley at [email protected] James Hertling