It will be a long time before it's clear exactly how the F word will apply to broker/dealers, brokers and financial advisors. Congress continues to debate reform legislation, with distinctly different bills being considered in the House and Senate. Final action is unlikely until at least the spring. (See “The Word on Reform” for a summary of legislation, below.) Meanwhile, new amendments can always slip in under the wire, and even after legislation is passed, regulators may be left to iron out the details.

Still, the outlines of the future have already been drawn. For one thing, it will become more difficult for an advisor to wear two hats: fiduciary and broker. Blurry divisions between those who provide investment advice, and those who only execute trades or sell products, will sharpen, say fiduciary experts and analysts. Advisors may also be required to provide simpler and more explicit disclosures describing the nature of their relationships with clients, including potential conflicts of interest — the sale of in-house IPOs and structured products, the sale of fixed-income offerings for which the broker/dealer conducts trades, as well as revenue sharing agreements and incentive compensation for different products. Today most of these disclosures are on firm websites or buried in account agreements.

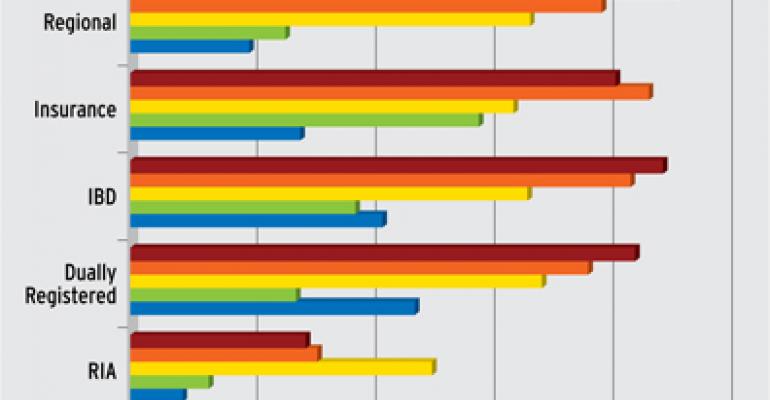

“This legislation is going to result in the bifurcation of the broker community,” says Don Trone, president and founder of the Foundation for Fiduciary Studies, a consultancy to firms interested in setting up a fiduciary process. Trone has provided testimony to Congress on the fiduciary debate. “The vast majority of brokers today are a little bit of this and a little bit of that — part-time broker and part-time investment advisor. The legislation is going to force advisors to make a choice, and firms, too.” Indeed, dual registration is popular these days: According to Cerulli Associates data, 85 percent of brokers and 30 percent of registered investment advisories (RIAs) are dually registered as both Series 7 registered reps, and Investment Adviser Act of 1940 investment advisor reps (IARs). “You may find some boutique b/ds emerge that only intend to remain broker/dealers, and vice versa. Some b/ds will evolve into RIA firms,” says Trone.

One big gray area is how b/ds will address the non-discretionary advisory account, a wrap account that brokerages created to replace the now defunct fee-based brokerage account. (Regulators banned fee-based brokerage accounts in the fall of 2007.) Collectively, non-discretionary wrap accounts hold $300 billion or more in assets. Today, when a brokerage FA creates a comprehensive financial plan for a client inside one of these accounts, the FA is subject to a fiduciary standard and must hold a Series 65 or 66 license. But typically, the fiduciary relationship terminates when the plan is delivered, and does not extend to implementation of the financial plan, or to other, existing brokerage accounts, according to disclosures on most brokerage firm websites.

In addition, under temporary rule 206(3)-3T, firms can conduct principal trades within non-discretionary advisory accounts for some securities as long as they have “blanket” client consent (rather than trade-by-trade). The rule expires in December of this year, but is expected to be renewed.

Only advisors who have full discretion over a client's account are required by law to act as fiduciaries throughout the advisory and investment selection process. And FAs with discretion probably represent at most 10 percent of advisors at firms like, say, Merrill Lynch or Morgan Stanley Smith Barney, say analysts, because the firms feel the legal liability is just too great. Training additional advisors to become fiduciaries in every step of the process, and training their branch managers to monitor them, is a big job, and it could take a lot of time and money, say executives and consultants.

“It's not good news for the traditional model of the retail brokers, and it probably makes the job substantially less fun,” says Brad Hintz, Sanford & Bernstein analyst and former CFO of Lehman, speaking of proposed reforms. “Because, if your job is to bring in assets, you're going to be very limited in your ability to provide advice to clients. The beauty of being a retail broker was the freedom he had to serve clients, serve as the trusted advisor. But the large bureaucratic organizations are going to be very careful about it. ”

Big Business

Firms may be reluctant to turn too many advisors into fiduciaries for other reasons, as well: Sales of proprietary products, principal transactions and selling agreements with third-party managers are all big business for most broker/dealer firms. Exactly how big varies firm by firm, but, for example, a Merrill earnings report shows that principal transactions alone accounted for nearly one quarter of revenues in the third quarter of this year. And in a June 25 research report on Morgan Stanley Smith Barney, Banc of America Securities-Merrill Lynch analyst Guy Moszkowski projected that a uniform fiduciary standard would squeeze returns on assets for big brokerage firms. “FAs will be expected to take into account not just whether a product or investment is suitable for the client, but also whether it is priced favorably relative to available alternatives, even though this could compromise the revenue the FA and company could realize. We expect this to exert downward pressure on revenue,” he wrote.

The fiduciary standard that currently applies to RIAs and IARs under the Investment Adviser Act of 1940 doesn't prohibit a broker/dealer or advisor from selling proprietary or commission-based products. It simply requires that any conflicts be disclosed to investors, and that a prudent process can be demonstrated for the selection of each investment.

“But then you get to the practical effect,” says Fred Reish, of law firm Reish & Reicher. “Some people might find certain disclosures distasteful — customers, broker/dealers or RIAs — and because of that some common practices will be changed. If you as a b/d went to the client, and said, ‘If you buy this thing we are going to make a ton of money off you,’ that just might not be palatable.”

Some b/d executives and industry lobbyists are pushing for carveouts for activities that do not include an advisory component — so the standard to be applied would depend on the particular service being sold, possibly in three tiers or more. A fiduciary standard would not apply, for example, where the relationship with the client was purely transactional. “If you're holding yourself out in the advice business you have to be giving them advice,” says Chet Helk, Raymond James Financial COO. “If you are holding yourself out as a product purveyor then you just have to make that clear to them. We don't want to force product manufacturers out of business. We just don't want them to misrepresent themselves,” Helk says.

These days most broker/dealer firms have selling agreements with product manufacturers, like mutual fund management companies, that explicitly state things like, “And you agree, b/d, to use your best efforts to sell our product,” says John Simmers, former chairman and CEO of ING Advisors Network. “As a fiduciary, what do you do when your b/d accounts for 10 percent of the sales of a particular product, and you're getting record-keeping fees, and other stuff. How does that turn out?” he asks. “It depends on carveouts and case law.”

Despite the lack of certainty about what new rules will take shape, some mid-sized dually registered firms are already preparing for the new regime, says Jason Roberts, a partner in the law firm of Reish & Reicher who specializes in employee benefits and securities regulation, and is the co-chair of the Financial Services Practice Group. His firm has been working with six large dually registered broker/dealer firms to identify potential conflicts of interest, create policies and procedures to mitigate those conflicts, levelize compensation, draft new client service agreements and investment policy statements and revise disclosure documents. In some cases, firms he is working with are even getting rid of revenue sharing agreements.

“Our general guidance is until we know enough about where the lines will be drawn, it's time to start thinking about a clear separation of product and advice,” says Roberts.