The Department of Labor’s final fiduciary rule, released Wednesday, differed enough from the proposed version that the DOL felt compelled to publish a lengthy chart detailing where the two diverged.

Mostly, commentators focused on changes to the so-called “best interest contract exemption,” or the hoops an advisor will have to jump through to continue getting paid in ways that might be considered unworkable in a true fiduciary arrangement, like sales commissions or revenue-sharing arrangements.

By the Labor department’s own admission, those hurdles were lowered, making it easier for a retirement advisor to work under the exemption. Detailed analysis of the impact of fees, considered by some an essential component for transparency, were largely curtailed in favor of “streamlined” disclosures of potential conflicts. Details will be available if the client requests them.

To continue working with retirement investors, advisors still need to make decisions in a client’s best interest, fees can’t be egregious and conflicts must be disclosed, but in the final rule an advisor is free to engage in any compensation structure to sell virtually any investment product available. That includes products with reputations for being very much not aligned with a retirement saver’s best interests, like variable annuities, non-traded REITs and listed options.

But some industry observers think the DOL took the adjustments too far.

“Wall Street Dodges a Bullet,” wrote Joshua Brown, CEO of Ritholtz Wealth Management in New York, on Fortune.com, noting that virtually all the products brokers sell will still be allowed as long as additional disclosures of conflicted business arrangements are made. “This will be no trouble at all: Just picture the speed with which you click “Agree” every time iTunes does a software update.”

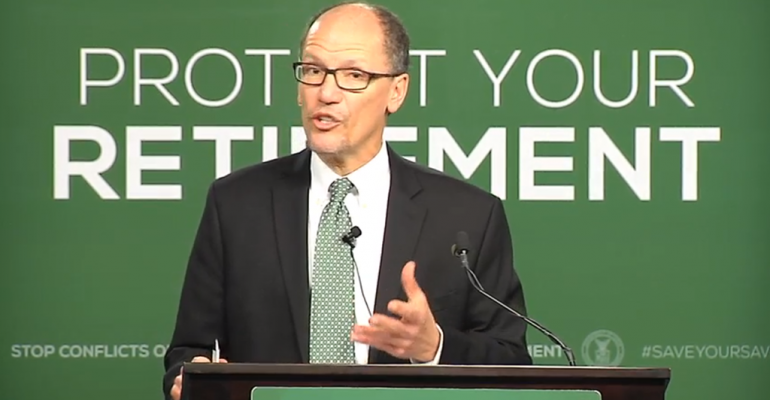

Thomas Perez, secretary of the Dept. of Labor, said “extensive feedback” from industry stakeholders led to the changes, including from the brokerage firms that will be most impacted.

That impact was most immediately felt in the stock market. Prices for brokerage firms like Primerica and Ameriprise jumped immediately after the rule was published. LPL, the largest independent broker/dealer in the country, was at one point up 7 percent. According to a Morgan Stanley analyst, the Department of Labor “meaningfully softened” the rule, and “that’s good news for those companies."

Knut Rostad, head of the Institute for the Fiduciary Standard, said “from Wall Street reactions, it appears we are aligned agreeing the final rule has been significantly softened. The difference is Wall Street likes it and I don’t.”

Andrew Stoltmann, a Chicago securities attorney, says that on the whole, the rule is a positive one for investors, but “it’s a watered-down version of what many of us thought would be a stringent fiduciary duty. There are carve-outs and holes in this rule that you could drive a pretty big Mack truck through.”

“Any fiduciary duty that can be discharged by disclosure is problematic,” he said. “They go in the trash just like the prospectus does. As a fiduciary, I can’t rely on disclosure.”

The best-interest contract exemptions that allow for the sale of investments like variable annuities, non-traded REITs and listed options, as long as the conflicts are disclosed and fees are not unreasonable, requires advisors to still commit to putting their clients interests first by mitigating the harm of those conflicts.

“To argue in, any instance, that a variable annuity in an IRA is the best option for any investor just doesn’t pass the red-face test,” Stoltmann said.

But some commentators suggested the DOL is taking a longer-term view by giving opponents a handful of concessions, while keeping intact what Perez repeatedly called the “North Star” of the rule, that advisors, regardless of context and regardless of investment product, put client interests ahead of their own.

In other words, though it is theoretically permissible under the contract exemptions, it is unlikely advisors will have any client for whom there is no better option for their retirement savings than a non-traded REIT or complex annuity.

“If we are setting ourselves up to lead with the exemptions, then we are going to fail,” said John Anderson, head of practice management for SEI Advisor Network. “We are starting from a position for the client that is a no-win.”

“The perceived conflict is still there. You are still going to have to explain your conflict. You are going to have to explain what your fees are,” he said. “I think they are trying to sell this first to the manufacturers. But this is the first shoe to drop. This is a first step and they’re taking it a little softer than they were originally proposing. Five years from now, it will be dramatically different than it is today.”

“There is no question they have scaled back disclosure requirements,” says Barbara Roper, the director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America. Still, she praised the rule for “closing the loopholes” so advisors “can no longer evade their obligation to serve their customers’ best interest.”

The rule demands firms with advisors working under the best-interest exemption “must have policies and procedures designed to mitigate harmful impacts of conflicts of interest,” according to the DOL. Mitigation should eliminate many of the “toxic conflicts that pervade the brokerage and insurance model,” Roper said.

By mitigating the harm of conflicts, firms will find they can no longer justify them, Roper said. Advisors could still be paid in commissions or other sales-based compensation structures, but firms won’t be allowed to incentivize one product over another. “Paying an advisor more to sell one fund over another? That won’t be allowed. Setting sales quotas won’t be allowed. A ratcheted payout grid? That should be gone,” under the terms of the DOL rule, Roper says.

“Hopefully this will put pressure on product sponsors to create products that can compete,” she said. “There is no reason that variable annuities have to be so costly. If you want to stay competitive with this market, revise the product so it can be sold in a best-interest standard.”