Progress Of Total Return Legislation

By Lyman W. Welch

Sidley Austin Brown & Wood, Chicago

The trend in evolution of total return legislation suggests that safe harbors and procedural limitations are advisable to protect the trustee from liability arising from important new powers.

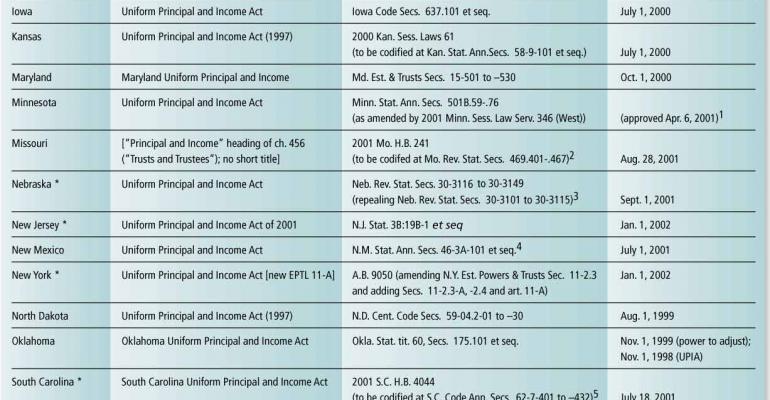

Almost half the states enacted Total Return Legislation in the past three years. (See Exhibit) Why? Trust income has fallen. A portfolio invested 60 percent in large cap stocks and 40 percent in intermediate corporate bonds yields about 2.5 percent compared to 5.5 percent ten years ago. Without Total Return Legislation, trustees of income trusts are forced to consider investing larger portions of trust funds in bonds that cannot grow in value over time, to the long-term detriment of both current and future trust beneficiaries. Also, there is pressure to tilt equity investments toward income stocks, increasing risk by overconcentrating investments in these sectors. Conflict results: how a trustee would invest to achieve the best total return too often conflicts with how a trustee would invest to achieve fair or necessary income distributions. This increases litigation risk and disputes, calling out for a solution.

What is Total Return Legislation? It frees trustees of income trusts to make investment decisions as the trustee thinks best without being captive to cashflow needs.

Two forms of Total Return Legislation have evolved. One approach grants trustees power to adjust distributable income by transferring principal to income (or vice versa) to the extent the trustee believes necessary to satisfy the trustee’s duty to be fair to both current and future beneficiaries. A second approach grants trustees power to convert an income trust to a unitrust. A few hybrids combine these two approaches.

Power to Adjust

The power to adjust was first adopted by the Uniform Commissioners on State Laws in 1997 as part of its revised version of the Uniform Principal and Income Act ("UPIA"). This revised act includes in Sec. 104 the power to adjust described above. Three years later, on August 3, 2000, the Uniform Commissioners approved an amendment to UPIA adding Sec. 105 to limit trustee exposure to liability in exercising or omitting to exercise this power to adjust.

UPIA Sec. 104 has three conditions before a trustee can exercise the power to adjust.

• The prudent investor rule applies, either by governing law, governing trust instrument or court order.

• The trust makes income a determining factor in the amount distributable.

• The trustee determines that the duty of impartiality requires an adjustment between income and principal.

In the 23 jurisdictions that have adopted UPIA Sec. 104, if the trustee’s investment decisions reduce income distributable to the current beneficiary below the level the trustee believes appropriate, the trustee has power to make an equitable adjustment, by transferring a compensating amount from principal to income.

Unitrust Conversion

A unitrust is a different solution to the same problem. A unitrust directs or permits the trustee to pay out a specific percentage of the trust, recalculated annually. The consequence is that current and future beneficiaries share as partners in the total investment results, and the trustee is freed to invest solely for total return unconstrained by cashflow requirements. The unitrust is increasingly popular among estate planners, and now three states have adopted Total Return Legislation permitting trustees to convert income trusts to a statutory unitrust.

Variations on a Theme

The rapid advance of Total Return Legislation sends a loud and clear message that there is a need. The patterns of variation in the Total Return Legislation enacted to date by 24 different jurisdictions shows evolution in search of the best solution.

Limits on payout discretion. Five of the states adopting total return legislation have put limits on the trustee’s discretion to adjust the payout percentage. Louisiana adopted UPIA Sec. 104 without adopting UPIA itself. Louisiana grants trustees discretion to adjust income and principal on the trustee’s own authority, provided that if a proposed transfer from principal to income would increase net income for the year above 5 percent of the fair market value of trust assets at the beginning of the year, then a court order is required. Louisiana also requires a court order if a proposed transfer from income to principal would reduce net income for the year below 5 percent of the fair market value of trust assets at the beginning of the year. New Jersey creates a safe harbor for the payout percentage, providing that a trustee’s decision to increase distributions to an amount not in excess of 4 percent or to decrease distributions to an amount not less than 6 percent of the net fair market value of trust assets at the beginning of the year shall be presumed fair and reasonable to all beneficiaries.

Delaware did not adopt UPIA Sec. 104 and instead adopted a liberal unitrust conversion statute, which gives discretion to the trustee to set the payout percentage between 3 percent and 5 percent, as well as discretion over a broad range of administrative policies, such as how to value assets and whether to average values over multiple years.

New York and Missouri both adopted UPIA Sec. 104 supplemented by a separate unitrust conversion statute. The Missouri unitrust conversion statute gives the trustee discretion to set the payout percentage at 3 percent or greater, with 3 percent as the default if no percentage is specified. New York fixes the unitrust payout percentage at 4 percent. Both Missouri and New York provide that trust assets be valued annually during the first three years and thereafter on a three-year average basis. By using a three-year rolling average of asset values to determine the payment amount, the distributions stream becomes more regular and smoothed.

Proposed Regulations were issued by the Treasury Department in February to revise the definition of income under Sec. 643(b) of the Internal Revenue Code to take into account changes in the definition of trust accounting income under state laws adopting Total Return Legislation. Importantly, these regulations specify that state laws providing payment to an income beneficiary of a unitrust amount of between 3 percent and 5 percent of the annual value of the trust is a reasonable apportionment of the total return of the trust, and rule that unitrusts and equitable adjustment trusts qualify as marital trusts and grandfathered GST trusts, but only in states adopting Total Return Legislation.

Procedural safe harbors. California, followed by a number of other states, modified UPIA Sec. 104 by adding procedures to safeguard the trustee from liability. For example, California added a provision that a trustee is not liable for not considering whether to make an adjustment or for choosing not to make an adjustment. Similar language was adopted by Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Minnesota, Nebraska, Tennessee, West Virginia and Wyoming.

California also adopted procedures for a trustee to give notice to beneficiaries of a proposed adjustment, and if no beneficiary objects in writing, the trustee may not be held liable for the adjustment. Similar language was adopted by Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Minnesota, Nebraska, Tennessee, West Virginia and Wyoming.

California also provides that the sole remedy in a proceeding contesting a trustee’s exercise or nonexercise of the power to adjust is for the court to direct, deny or revise the adjustment. Similar language was adopted by Colorado, Hawaii, Minnesota and Tennessee.

Seven states have adopted UPIA Sec. 105 on "Judicial Control of Discretionary Powers," which was added to UPIA by amendment in August 2000. This provision protects a trustee’s decision to exercise or not exercise the power to adjust by mandating that the trustee’s decision is final unless a court finds the decision was an abuse of the trustee’s discretion. Further, Sec. 105 provides that if an abuse of discretion in the exercise or nonexercise of the power to adjust is found, the remedy is to require make-up adjustments from or to the trust fund. Only as a last resort, if the court is unable to restore the beneficiaries or the trust, may the court surcharge the trustee personally. UPIA Sec. 105 was adopted by Arizona, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina and Wyoming. The New York version adds language that the court may not require the trustee to personally pay damages unless the court finds that the trustee was dishonest or arbitrary and capricious.

Effective date limits. Most total return legislation applies both to pre-existing trusts and to newly created trusts unless the governing trust instrument specifically directs otherwise. However, a few states have limited effective dates. Alabama provides that UPIA Sec. 104 applies only if the trustee or any beneficiary obtains court approval to be governed prospectively by it, or if the written consent of all current income beneficiaries and presumptive remaindermen is obtained. Louisiana’s UPIA Sec. 104 applies to trusts created after January 1, 2002 and, as to pre-existing trusts, is not effective until January 1, 2004 unless all current beneficiaries or the governing instrument designates an earlier effective date. Missouri’s unitrust conversion statute applies to trusts created after August 28, 2001 unless the governing instrument clearly directs otherwise, and further applies to pre-existing trusts if the trustee elects to convert to a unitrust by an August 28, 2003 deadline. The New York unitrust conversion statute permits trusts created after January 1, 2002 to convert only within two years of funding, and pre-existing trusts may be converted only on or before a December 31, 2005 deadline.

Conclusion

Total return legislation is needed, as demonstrated by its adoption in almost half the states. It is needed to grant trustees discretion to solve the total return versus income trust conflict by disconnecting investments from cashflow requirements. The trend in evolution of total return legislation suggests that safe harbors and procedural limitations are advisable to protect the trustee from liability from the good faith exercise or nonexercise of these important new powers.u

Lyman W. Welch is a partner in the Chicago office of Sidley Austin Brown & Wood who concentrates in all phases of trust and estate work, with special interest in estate planning for executives and family business owners. He serves as counsel to bank trust departments, closely held corporations and charitable organizations.