Casey Kasem died on June 15, 2014 in hospice care in Seattle. Born in 1932, Kasem, a legendary disc jockey, originator and long-time host of American Top 40 and voice of “Shaggy” Rogers in the Scooby-Doo cartoon series, was highly successful. By all accounts, he lived a full and fulfilling life–up to his last few years, however.

In 2007, Kasem was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, although later his family said he suffered from Lewy body dementia, a progressive disease of the brain that exhibits symptoms very similar to those of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s dementia. Shortly thereafter, in 2007, Kasem signed an advance health care directive placing his daughter and her husband in charge of his medical affairs. Due to his condition, he was no longer able to speak.

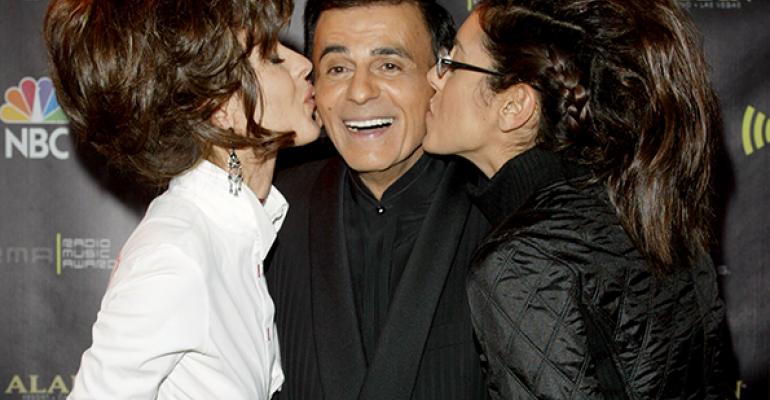

Kasem’s first marriage, from 1972 to 1979, produced three children: Mike, Julie and Kerri. Kasem remarried in 1980 to Jean Kasem. That marriage lasted until his death.

So, in 2013 Kasem had three adult children, the oldest, Kerri, age 40. He also had a wife of 34 years with whom he lived in Santa Monica, Calif. At some point, his wife admitted him to a nursing home.

By 2013, Kasem’s health had severely deteriorated. In the spring of 2013, Jean stopped allowing the children from Casey’s first marriage to see their father. Why she cut off contact is not known. But based on what happened next, it’s pretty apparent that there was bad blood between the children and their stepmother. So much so that on Oct. 1, 2013, the three children publically demonstrated in front of Jean’s house in protest of not being allowed any contact with Kasem. Next, the children went to court seeking conservatorship (as California calls guardianship). The court feud centered on visitation rights, whether Kasem was receiving proper care and what was in his best interest in light of his declining health.

On May 7, 2014, Jean removed Kasem from the nursing home, and as was later learned, spirited him away to Seattle. Meanwhile, on May 12, a California court, over the objections of Jean, granted Kerri temporary conservatorship over her father. The California court ordered separate visitation rights for the children. In his 2007 health care directive, Kasem had named Kerri as his health care surrogate. Based on his condition and the instructions in the 2007 health care directive, Kerri asked the court to allow her to terminate life support for her father. She relied on language in his health care directive calling for termination of life support if he was “devoid of cognitive function” and there was no hope of recovery. In response, the court ordered that Kasem be fed, hydrated and medicated. The next day, having learned that Kasem was not responding, the court, over the strenuous objections of Jean, ordered termination of artificial nutrition and hydration. Kasem died soon thereafter.

How did it come to this–Kasem being spirited away, his daughter having to go to court and his wife so upset at the daughter’s actions that the wife resorted to hurling frozen meat at the children?

Kasem had planned ahead. In the early stages of his illness, he signed a health care directive, included instructions about end-of-life treatment and named a surrogate decision maker. What he failed to appreciate, however, was the depth of family animosity and distrust between his second wife and the children of his first marriage. The decisions about his care became the battleground between Jean and his children–and it was a battle that was likely about a lot more than just his medical condition.

The children had probably always resented Jean, who married Kasem only a year after his divorce from their mother. The children may have believed that Jean broke up the marriage and caused deep pain to their mother. There wasn’t much they could do about that at the time.

But when their father’s health declined, it was time to take action. And, when Jean’s decisions about their father’s care seemed problematical—he was found to be suffering from serious bed sores—the children rushed into court to “save” him. Ironically, it was Kerri, who as the surrogate had authority to make decisions about his care, that ultimately made the decision to terminate Kasem’s life, and it was his wife who yelled at the judge who approved Kerri’s decision, “You have blood on your hands!”

Could this family psychodrama have been avoided? We don’t know why Kasem named his daughter, rather than his wife, as his health care surrogate. But by doing so, he almost assured a future family feud. The second wife was naturally going to resent not being chosen as the surrogate. She wouldn’t have seen herself as a “second wife” but, in this case, as a wife of over 30 years. Yet despite the passage of time, the children may still have seen her as an interloper who broke up a happy family. Flash forward to the last weeks of Kasem’s life, and it’s no surprise what happened.

Of course, the wife could have been kinder and let the children visit their father. And, the children might have been less critical of her care. By the time the children filed for conservatorship, however, the hostility was so intense that nothing that happened next was a surprise. The wife, fearing that she was losing control of her husband, ran away with him. The children tracked them down, and Kerri asserted her rights as a surrogate.

The court also played its role when the judge apparently believed that he, rather than Kerri, should direct Kasem’s end-of-life medical care. Finally, reality trumped judicial arrogance and Kerri was permitted to carry out her father’s wishes and let him die.

Could Kasem and the attorney who, in 2007, drafted the health care directive, have avoided this sad scenario? Unlikely. Jean was determined to “care” for her husband, despite his explicit instructions that Kerri was to decide how he should be cared for as death neared.

As they say, you can have them sign documents, but you can’t make them follow what the documents say. Unfortunately, too often emotion trumps the law–at least in the short run. This saga emphasizes the importance of not only having advance directives, but also that of speaking with your family members about your wishes under those directives to try and avoid any conflict in advance.

Lawrence A. Frolik is a Professor of Law and Distinguished Faculty Scholar at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

Bernard A. Krooks is a founding Partner of the New York City, White Plains and Fishkill, NY law firm of Littman Krooks LLP.