With the stock market at all-time highs and volatility normal, it’s easy for retirees, near-retirees and even advisors to get complacent about sequence risk, one of the biggest dangers to a retirement nest egg and saver’s peace of mind. No one knows exactly when the next big market correction will occur, but when it does, like we saw in 2000-2003 and 2008-2010, sequence risk (aka sequence of returns risk) can wreak havoc on retirement projections and planning.

Sequence risk refers to the devastating impact that poor investment returns can have on a retiree’s savings if they occur in the early years of retirement—or shortly before someone plans to retire. It can cause a retiree’s income to drop significantly or induce a downward spiral that’s hard to escape.

Taking distributions when the market has precipitously declined effectively “costs” the retirement plan more than it can sustain. This causes a retiree to make major economic adjustments to their forthcoming distributions and lifestyle—something nobody wants to deal with at any age.

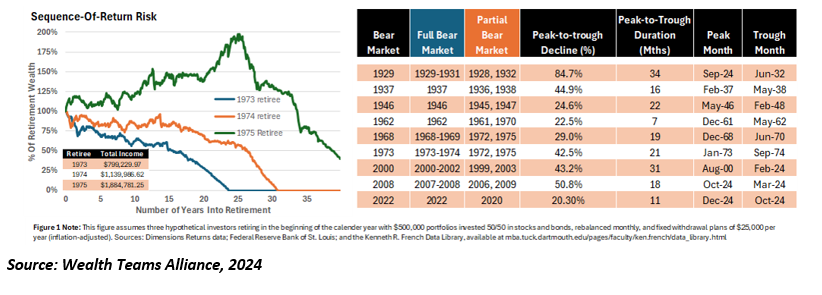

The table below shows the impact of sequence risk on three investors who first started taking distributions in 1973, 1974 and 1975, respectively. The assumptions were based on each investor withdrawing $25,000 a year of income, plus inflation.

Depending on when each investor started taking distributions, the outcomes are quite different. Investor 1 (starts in 1973), Investor 2 (starts in 1974) and Investor 3 (starts in 1975).

Even if each investor started with $500,000 in a balanced portfolio (evenly split between stocks and bonds) and rebalanced monthly, they would have achieved vastly different long-term results. Also assume the portfolios were each the investor’s sole source of income for 35 years of retirement and that each withdrew $25,000 per year (5%), adjusted for inflation.

Before considering withdrawals,

- The 1973 retiree had a long-term return of 7.12%.

- The 1974 retiree had a long-term return of 8.81%.

- The 1975 retiree had a long-term return of 14.12%.

After factoring in withdrawals, they experienced widely divergent lifestyle outcomes as well. The 1973 retiree, who left work in a severe bear market decline, would have run out of money after just 24 years in retirement. By postponing retirement just one year, however, the 1974 retiree—who left work at the tail end of the 1973-74 bear market—would have seen their nest egg last for 31 years. The 1975 retiree, who left work at the beginning of a bull market, by contrast, saw substantial growth in her retirement account and was able to leave a bequest of about $135,000 after 40 years of retirement.

Again, here are some of the biggest dangers of sequence risk:

- Impact on portfolio longevity. If a retiree experiences negative returns early in retirement and withdraws funds from their portfolio during those years, they can deplete their nest egg much faster than expected. This can cause their portfolio to fail prematurely. Once a downward spiral begins, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to escape it.

- Sequence matters. The order in which investment returns occur has a significant impact on a portfolio's overall growth and longevity. Experiencing negative returns early in retirement can be more detrimental to a retiree’s long-term distributions than experiencing the same negative returns later in retirement, i.e., after the portfolio has had more time to grow.

- Withdrawal rate considerations: Sequence risk is closely tied to a retiree's withdrawal rate. Higher withdrawal rates increase the impact of sequence risk. That’s because a larger percentage of the portfolio will be withdrawn when potential negative returns could deplete the account faster.

Four Ways to Minimize Your Clients’ Sequence Risk

1. Maintain spending flexibility. Here we maintain a balanced investment portfolio while allowing for flexible spending. We mitigate sequence risk by reducing spending after a portfolio decline. This allows more money to remain in the portfolio so it can take part in any subsequent market recovery. However, the retiree has less spendable income during this period.

Withdrawing a constant percentage of remaining assets minimizes sequence of returns risk. It is important not to put too much pressure on the portfolio during the early years of retirement. While a constant withdrawal percentage can reduce the pressure, if the portfolio drops 20% to 30% in one year, then withdrawing an income only increases the amount the portfolio must recover. This is a dangerous strategy and can cause a depletion of assets in the future.

2. Reduce volatility (when it matters most). Essentially, investors should not expect constant spending from a market-based portfolio since the likelihood of volatility is too high. Those who want upside—and who are willing to accept volatility—should be flexible with their spending and consider abstaining from withdrawals until the storm passes. Retirees can reduce volatility by building a portfolio based on distributions instead of growth. This means they set aside expected distributions into a bucket and then invest the remaining portfolio without withdrawing funds.

Spending could remain constant if the portfolio was “de-risked.” To get constant spending, clients could look to hold fixed-income assets to maturity or use risk-pooling assets like income annuities or other fixed assets. Other approaches to reducing downside risk (volatility in the undesired direction) could include using a rising equity glide path in retirement. The path starts with an equity allocation that is even lower than typically recommended at the start of retirement but then slowly increases the stock allocation over time. Doing so can reduce the probability and magnitude of retirement failures. This approach reduces vulnerability to stock market declines early in retirement that cause the most harm to retirees.

Asset allocation could also be achieved with a funded ratio approach. Here, more aggressive asset allocations are used only when sufficient assets are available beyond what is necessary to meet retirement spending goals. Finally, financial derivatives or income guarantee riders can be used to set a limit on how low a portfolio can fall by sacrificing some potential upside.

3. Buffer assets—avoid selling at losses. Here clients place other assets available outside the financial portfolio from which to draw after a market downturn. Returns on these assets should not be correlated with the financial portfolio since the purpose of these buffer assets is to support spending when the portfolio is otherwise down. An old strategy in this category is to maintain a separate cash reserve—say two or three years of retirement expenses—separate from the rest of the investment portfolio.

While buffering assets is a safe approach, there’s the opportunity cost of not having those assets in other higher-yielding areas. Since cash can be a drag on a portfolio, “alternatives” have been increasingly used in recent years.

4. Bucket strategy: This involves segmenting a retirement portfolio into different "buckets" or asset pools, with each bucket serving a different purpose (e.g., short-term cash needs, medium-term investments, long-term growth).

The idea behind this strategy is to access cash in the short term so a retiree does not have to worry about stock market fluctuations. In theory, they shouldn’t have to sell their investments during a down market to fund their annual withdrawals.

Here Are Suggested Allocations for Each of the Three Buckets:

- The Immediate Bucket contains short-duration CDs, T-bills, high-yield savings accounts, and other similar assets. Ideally, clients hold enough cash in the immediate bucket to fund up to two years’ worth of living expenses.

- The Intermediate (Middle) Bucket covers expenses from Year 3 through Year 10 of retirement. Money in the intermediate bucket money should continue to grow to keep pace with inflation. However, investors will want to avoid investing in high-risk assets. Possible financial instruments include longer-maturity bonds and CDs, preferred stocks, convertible bonds, growth and income funds, utility stocks, REITs and more.

- The Long-Term Bucket contains investments that align with historical stock market returns. These assets grow a client’s nest egg better than inflation while also allowing them to refill their immediate and intermediate buckets. Here, we place a diversified portfolio of stocks and related assets. It should be allocated across domestic and international investments, ranging from small-cap to large-cap stocks.

Investors trust you to do what’s always in their best interests. They’re not as focused on returns as they are on protecting their capital. Your value comes from reducing financial (and psychological) risk and providing a long-term investment framework that can weather any financial storm.

Dr. Guy Baker is the founder of Wealth Teams Alliance (Irvine, CA).