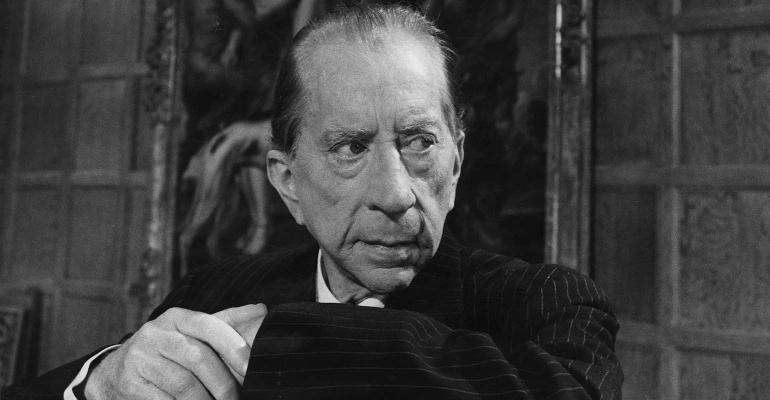

In this week’s issue of The New Yorker magazine, Evan Osnos’ article, “The Getty Family’s Trust Issues” contains a lot of important messages about family legacy planning. Although the premise of the article is to explore how oil tycoon J. Paul Getty’s heirs have successfully avoided paying millions of dollars of tax, there’s a lot to learn from the Getty family story beyond how they managed to save tax. As he was writing the article, Osnos contacted me to discuss not only Getty-type tax saving tools, but also broader trends in estate planning. I was honored to provide input for the article about the planning opportunities in the “Golden Age” of estate planning but cautioned that the Golden Age likely won’t last forever.

Techniques Used

First, let’s address some of the tools. Osnos points out that J. Paul Getty, America’s richest individual, avoided estate tax on his art, property and land by bequeathing them to a museum trust that established The Getty Center, one of the most visited of all America’s art museums. Paul’s son Gordon Getty, a San Francisco philanthropist, left four sons from wife Ann plus three daughters from an extramarital affair. Gordon included his three daughters in his estate plan by creating a trust for them called the “Pleiades Trust,” named for a group of Greek mythology sisters who had affairs with Olympian gods and were rewarded by becoming stars in the sky. Much of Osnos’ article is devoted to lengths taken by the Getty family to save tax, specifically by domiciling the trust in Nevada to escape California state income tax on the trust income. The trust tax arrangement is exposed by the Gettys’ disgruntled wealth manager Marlena Sonn.

Osnos also references other favorite techniques in the estate planner’s playbook, notably spousal lifetime access trusts, charitable reminder unitrusts, beneficiary defective inheritance trusts and grantor retained annuity trusts. He shares that the Gettys share the use of such tools with other mega-wealthy families, such as heirs of Walmart founder Sam Walton and casino owner Sheldon Adelson. Other dynastic families also receive shout-outs for their efforts to use such tools, including owners of Gallo wine, Campbell’s soup, Wrigley gum, Family Dollar, Public Storage and Hot Pockets. Osnos also highlights the strategy of holding appreciated assets until death and getting a stepped-up basis, pointing out that Jeff Bezos would avoid tax on a hundred billion dollars of Amazon stock gains if he died tomorrow. To pay living expenses without having to sell the stock during life, many owners of appreciated stock borrow against the stock and live off the loan proceeds, holding the stock till death (described as “buy, borrow, die”).

Out in the Open

The important point I want to make is that these techniques are perfectly legal. Osnos draws a distinction between tax avoidance (such as through use of these tools, which is legal) and tax evasion (such as failing to report income or overstating deductions, which is illegal). However, articles like this one and others are shining a light on many of the tools that in prior decades were flying under the radar. Most notably, “For the 99.8%” tax legislation proposed by Senator Bernie Sanders in 2021 aimed to kill a number of these tools but would grandfather anyone who had used them prior to the law’s passage. The law didn’t pass, but the publicity around it stirred up a public sentiment to tax the rich, as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s met gala gown proclaimed in huge red letters. As I pointed out in Osnos’ article, “Now that the general public is aware, there is a growing outcry to shut down these benefits. This is a wake-up call that, sooner or later, the tax landscape will likely drastically change.” Those who wish to take advantage of the current opportunities would be wise to act now.

Competing Philosophies

There is more to Osnos’ story about the Getty family than tax avoidance. He also describes competing philosophies among the heirs regarding the purpose of the family wealth. There are different views on where to invest and what causes to support. Dysfunction in the Getty family abounds. Old Paul had five divorces and five sons, whose weddings he didn’t even attend. After his death, the family feud was played out in public view in the courthouse, leading to a forced sale of Getty Oil to Texaco. One of Gordon’s daughters, a beneficiary of the Pleiades Trust, laments that her “abrupt transformation into an heir gave her little preparation for managing a fortune. ‘In exchange for the love I didn’t receive in my life, I got money,’ she said. ‘So, at first, I always felt misery and guilt, and I didn’t know what to do with it.’”

Head and Heart Estate Planning

The Getty story is an extreme case of what drives my passion for “head and heart” estate planning. In conjunction with expanding someone’s inheritance through creative tax planning, the estate planning process must also prepare the heirs to be responsible inheritors. Just like the Getty heirs, family members won’t always see eye-to-eye. Communication styles and love languages will differ. But a successful family addresses these matters rather than sweeping them under a rug. The end result is improved communication and trust, as well as family interdependence, so a family is there for each other as a support team when needed.