Many market observers have pointed out similarities between the current downturn in commercial real estate and the downturn in the early 1990s. Both were preceded by an extended period of relaxed underwriting standards, excess capital chasing returns, significant cap rate compression, and steep increases in asset values. It is useful to compare and contrast key elements of the two periods in order to establish a reference point for today’s investment strategies.

Two key regulatory changes during the 1980s paved the way for the overbuilding that defined the 1990s recession in commercial real estate. The 1982 tax cuts included provisions that allowed for generous depreciation allowances and tax shelters for investors. Also during the 1980s, the deregulation of the savings and loan industry allowed these institutions to expand their investments to include commercial mortgages.

The tax laws were changed again in 1986 to remove many of the earlier incentives for real estate investment. But the combination of a general atmosphere of economic recovery, an increasing appetite for real estate investment from institutional capital, and the introduction of the S&Ls as new and often inexperienced lenders for commercial real estate resulted in a massive oversupply of space in many markets.

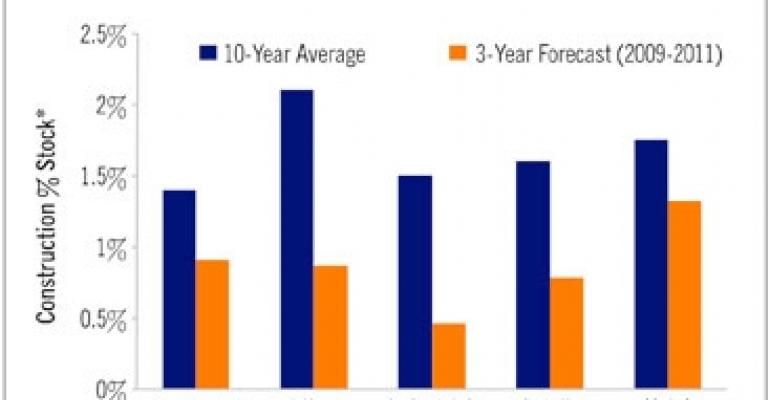

The silver lining in today’s environment is a general lack of oversupply in most markets. New construction in nearly every sector has been below long-term trends, though some markets are struggling with oversupply problems [Figure 1]. While ample financing was made available for development projects in recent years, the combination of supply constraints and sharply rising land and construction costs helped to keep new supply largely in check.

The primary problem for commercial real estate today is a lack of demand, caused by an economic recession that includes significant job losses, a historic decline in consumer spending, a global slowdown in import and export activity, and the collapse of the residential housing market.

The recession is reaching all property types, and vacancy rates are expected to approach or surpass 20-year highs. The lack of financing for new construction will likely keep new supply further constrained for some time, helping to improve real estate fundamentals as the economy recovers over the next few years.

FIGURE 1: NEW SUPPLY REMAINS IN CHECK COMPARED TO HISTORIC RATES

Dealing with distressed assets

The collapse of the commercial real estate market in the 1990s led to the passage of the Financial Institutions Recovery, Reform and Enhancement Act (FIRREA) of 1989. That legislation, aimed at bailing out the savings-and-loan industry, established the Resolution Trust Corp. (RTC), which was charged with efficiently selling off the enormous quantity of bad commercial mortgages from failed financial institutions.

The RTC took over distressed assets from failing lenders and owners and facilitated a quick and painful write-down. The RTC forced the clearing of defaulted loans and helped to establish pricing, which allowed transaction activity to recover relatively soon after the market collapse. Once clearing prices were established, private capital moved in rather quickly, accelerating the bottoming-out process and eventual recovery.

In contrast, today there is little pressure from the government on the banks to mark their real estate portfolios to the market level. A series of plans and programs aimed at dealing with distressed assets — including the Troubled Asset Relief Program, Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, and the Public-Private Investment Program — have helped to avoid financial catastrophe. But these initiatives have had minimal impact in terms of actually addressing the distressed assets that were central to the financial crisis.

Most lenders are not willing to foreclose on troubled properties primarily because their balance sheets are already impaired to the extent that they generally lack sufficient capital to support significant write-downs. Some lenders and special servicers are playing “pretend and extend” as they extend loans to buy time rather than pursue foreclosures and take mark-to-market losses. As a result there have not been as many distressed transactions as market experts anticipated.

Complex capital stack

Real estate financing leading up to the 1990s recession was fairly simple. Life companies, pension funds and commercial banks provided the bulk of funding and held mortgages on their balance sheets that matched their long-term liabilities. In the wake of the 1990s collapse of commercial real estate, these traditional lenders pulled back sharply, focusing their capital on the refinancing of existing assets.

Eventually, new capital began to flow into the market to take advantage of distressed pricing, with valuations falling between 30% and 50%. Capital came from opportunistic investors and later from a revitalized REIT industry buoyed by tax reforms.

The same FIRREA law that established the RTC also helped pave the way for the development of the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) model, which revolutionized real estate finance. Because of the risk-adjusted capital requirements that FIRREA placed on financial institutions, they were encouraged to hold securitized assets rather than whole loans.

Bankers eventually modified the long-standing residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) model to apply it to commercial real estate assets, opening up another new financing source.

The demand for CMBS encouraged investment banks and conduit lenders to originate massive volumes of new loans. A new moral hazard in the model emerged because CMBS loans are not held on the originator’s balance sheet, causing reduced incentives for rigorous underwriting. Competition among lenders led to increasing loan-to-values and lower pricing, which helped fuel the sharp spike in real estate prices.

In addition, borrowers looking to minimize financing costs and equity contributions often supplemented senior mortgages with an increasingly complex array of subordinate financing, including mezzanine and preferred equity positions. The complexity of the new capital structures, especially for CMBS pools, has created a nightmare for workout situations.

In the last downturn, the workout mechanism was relatively simple, primarily involving a single lender and borrower. Today, the complicated capital stack makes sorting out the interests of the different players more complicated, time-consuming and expensive. With competing interests of the various tranches engaged in tranche warfare, it is even more challenging to form an agreement in the restructuring process.

Impact of institutional ownership

Over the past 15 years, commercial real estate has been increasingly accepted as a mainstream asset class by large pension funds and other financial institutions. The market value of the NCREIF Property Index — which tracks institutional investment in U.S. commercial real estate — surged by eight-fold, rising from $41 billion in 1994 to $328 billion in 2008.

While recent investments by institutions — particularly those at the top of the market in 2006-2007 — have likely suffered declines in value, they often have the financial capacity to support their investments through additional capital. In short, these institutions can help to extend or restructure debt to avoid foreclosure. We believe that this is another reason that we have seen relatively little in the way of distressed asset sales.

David Lynn is managing director and head of U.S. research and investment strategy with ING Clarion based in New York.