It’s increasingly easier to find information about almost anyone on the internet. Individuals in the public eye, including celebrities and the ultra-wealthy, know that whether the information is positive or negative, it’s probably out there somewhere. But what do we do when we find out an individual in the public eye doesn’t share our core values or is actually a criminal?

Some might see a moral obligation to cut ties with that individual. She might stop following him on social media, boycott his products or stop watching his movies. But, the question becomes exponentially more difficult when it’s a charitable organization trying to decide what to do with a large gift from that individual. Often, to keep the organization running, charities rely on a few wealthy benefactors to make regular contributions. Now, charities are under intense scrutiny to examine the source of their donations to ensure they aren’t coming, directly or indirectly, from what some in the public sphere may consider “undesirable donors.” Here are some current examples of the moral and reputational dilemmas charities can face.

Recent Events

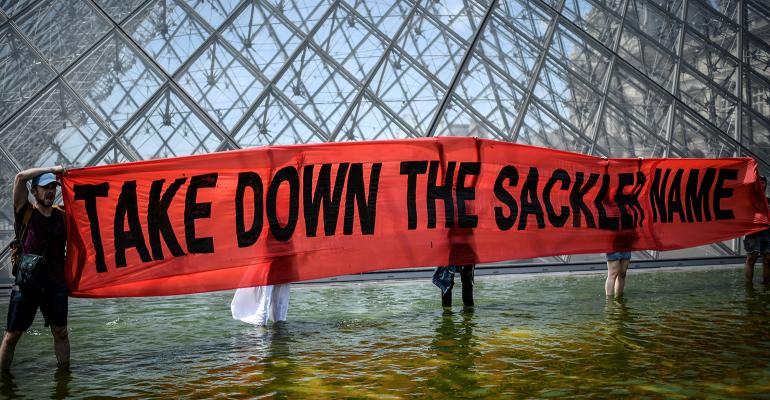

In light of the ongoing opioid crisis and protests at museums throughout the United States and England, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Tate and Britain’s National Portrait Gallery announced they aren’t currently accepting or seeking contributions from the Sackler family (owners of Purdue Pharma and creators of OxyContin).

In June, the University of Alabama School of Law returned a $21.5 million gift from H.F. Culverhouse Jr., a Florida real estate investor and lawyer. After Alabama enacted a restrictive abortion ban, Culverhouse publicly encouraged students to boycott the university. The school of law, named for Culverhouse, maintains the decision to return the gift was made because Culverhouse attempted to interfere with the law school’s operations and not because of his comments regarding the abortion law. Ultimately, Culverhouse’s name was stripped from the law school.

Harvard University recently reviewed previous contributions received from Jeffrey Epstein and his foundation, between 1998 and 2007. Harvard has no plans to return these gifts. Epstein was a convicted sex offender who faced federal sex-trafficking charges. His 2003 donation of $6.5 million funded a mathematical biologist who later established Harvard’s Program for Evolutionary Dynamics. Harvard explained that the majority of funds from previous gifts from Epstein have already been spent for their intended purposes. Harvard has decided to redirect the remaining unspent funds of $186,000 to organizations that support victims of human trafficking and sexual assault. Harvard didn’t uncover any gifts from Epstein or his foundation dated after his guilty plea in 2008 and specifically rejected a gift following his conviction in 2008.

Other Considerations

Putting aside the ethical and public perception considerations, there are other issues for charities to consider when returning a gift. For example, charities could be bound by contract or state law to keep the gift or fulfill naming rights. Courts have upheld gift agreements involving naming rights and have compelled charities to either refund the gift or keep the name, even if it no longer reflects the charity’s mission. The Smithsonian received millions of dollars from the Sackler family, but it claims that it’s bound by contract to keep the Sackler name on its gallery. While Yale will also keep the Sackler name on one of its reendowed institutes due to contractual obligations, it’s decided to distance itself from the family. Some charities are starting to build into gift agreements a clause that allows the charity to terminate any naming rights in the event of significant negative public attention.

There can be unfavorable tax consequences for the donor if a gift is returned. The tax benefit rule, found in Internal Revenue Code Section 111, requires taxpayers to include the return of items deducted in earlier years in their income. If the donation is returned, the donor would likely need to include the donation in income to the extent that deductions on prior returns reduced tax liabilities, subject to tax at the rate in effect during the year of recovery. A mismatch would result if the donor is in a different tax bracket when the contribution is returned.

Now, more than ever, charities must know where their funding comes from. They face a difficult decision if negative information about a donor surfaces after they accept a gift. The charities must consider the potential damage to their reputation if they keep the gift and weigh it against the legal, ethical and financial ramifications that come with returning it. Like the charities mentioned above, charities can decide to reject any future donations from unfavorable donors. They can also return contributions, like the University of Alabama School of Law, or, like Harvard, they can decide to keep the funds. Ultimately, the charities must decide what’s best for themselves and their other supporters, but having all of the facts (and a strong gift agreement) is critical.