By James Tarmy

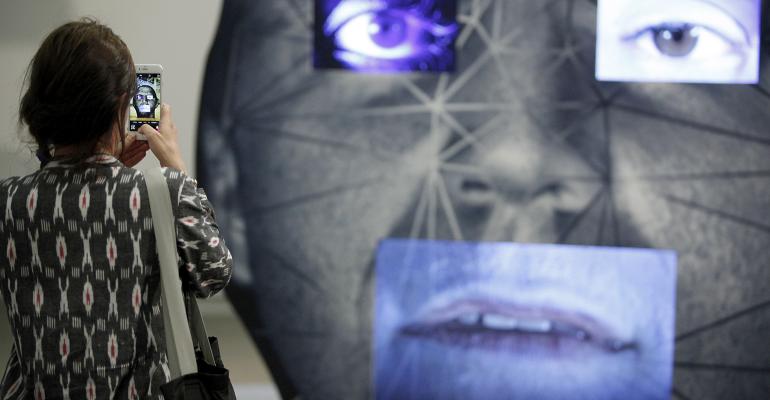

(Bloomberg) -- During the opening of Art Basel’s Unlimited section on Monday in Switzerland, technicians in jumpsuits pushed life-size, three-dimensional models of cars through a mechanismthat sprayed acrylic paint. Around the corner, a 30-foot-long blow-up sculpture of a Nike sneakertowered over passersby. Across the hall, two 62-foot-long walls were covered in banners highlighting 200 people accused of sexual harassment.

These artworks are for sale, but this is not the kind of art that would end up in a house, let alone on a living room wall.

Instead, this section of Art Basel, which opened to VIPs on Monday and will runs through Sunday, June 16, is geared, perhaps more than ever, to high-spending private foundations.

“We’re working with private collectors who have museums,” says Alexander Hertling, the co-founder of the Paris gallery Balice Hertling, which has co-presented a 20-foot-long, mostly wooden sculpture by Camille Blatrix, which comes with a 10-foot-high, pear tree wood mirror, and is on sale for €90,000 ($102,000). “They can be in Beirut or Paris or Venice, but these people didn’t really exist 10 years ago.”

Art World Funhouse

Art Basel, which is set in a cavernous convention center on Basel’s Messeplatz, is broken up into a series of sections—“Features” for historical art, “Statements” for solo booths, and so on—but the major divide is between the main hall, where dealers have booths, and the Unlimited hall, which resembles a very expensive, relatively freewheeling art world funhouse.

In theory, every work dealers bring to the fair is vetted by a committee at Art Basel in order to guarantee the fair’s overall quality. While matters might be a bit more lax on the booth side of the convention hall, it’s rigidly enforced on the Unlimited side, which is officially curated by Gianni Jetzer, the curator at large for Washington’s Hirshhorn Museum.

This year, there are 75 projects. Each, in some way, is supposed to be something that couldn’t fit in a normal art fair booth. Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner, for instance, are co-presenting an installation of 28 colorful sofas by Franz West, which sold on the second day for $3.8 million.

“The nature of Unlimited is that you submit these proposals for enormous things that could, broadly speaking, never fit in anyone’s house,” says Alex Logsdail, the executive director of Lisson Gallery. He brought to the fair 18 panels by artist John Latham, which together measure about 50 feet. “It’s a big, big thing, and it requires a lot of space, and it requires a sophisticated collection,” he continues. “Which, in typical terms, is going to be a public private space or a museum.”

Unlimited, in other words, was always a place where dealers brought big art that would work best in a museum. What’s gradually changed, dealers say, is the expectation that the works will actually sell.

In the last decade, several major private museums opened their doors: Mitchell and Emily Rales’s Glenstone, located in Potomac, Md., opened in 2006, followed by a second, $200 million expansion last year; the Walton family’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ark., opened in 2011; Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei’s Long Museum in Shanghai was founded in 2012.

“There are so many collectors that have such huge private foundations and museums,” says Wendy Olsoff, the co-founder of P.P.O.W. gallery, which brought a collection of eight films and 39 photographs and works on paper by Martha Wilson, collectively known as the Halifax Collection. “They’re a big part of the art world now.” (Olsoff is currently in “two conversations” with institutions who’d like to buy the collection.)

Time for Showstoppers

After spending years building these collections, dealers say these private institutions are in the market for showstoppers.

“You wonder who on Earth is going to buy [ambitious art] and house it,” says Jason Ysenburg, a director at Gagosian, which brought a 28-foot-long, three-dimensional sculpture by Tom Wesselmann from 1973, priced from $5 million to $8 million. “And yet you see private museums like Glenstone appear, where they are interested in challenging artists [who] push the limit.”

At public museums, in contrast, “there has to be various approvals, and it can take a long time,” he explains. “Which is why these private museums and foundations are quick—nobody has to wait for board approval.”

That speed, Ysenburg says, is why the gallery decided to bring the Wesselmann work to Switzerland.

“We showed all nine [of this series] together in New York and produced a catalogue,” he continues. “The show generated a lot of interest, and there were some museums that were interested. But they had to find people to give them money, and they have other agendas.”

As a result, “we thought it was a good idea to bring the work here, because Unlimited is packed with people from private institutions.”

But there are no guarantees. “Dealers always have hopes for all the things they want to come true,” P.P.O.W.’s Olsoff says. “Everyone wants a museum to buy it, and everyone wants to go home happy. But it’s always a crapshoot.”

To contact the author of this story:

James Tarmy in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Gaddy at [email protected]