There was a time when falling oil prices were considered a boon to U.S. consumers. The logic is clear; lower energy prices, especially at the gas pump, were a cash windfall, an effective tax cut and spent accordingly.

With oil prices near their lowest levels in 10 years and gas prices similarly "cheap" you might think there would be more chatter about the benefit to the consumer, and thus to consumption and to the economy as a whole. But there are some good, structural reasons that lower energy prices are not quite the windfall they once were. And for the energy industry at least, they could prove quite deleterious.

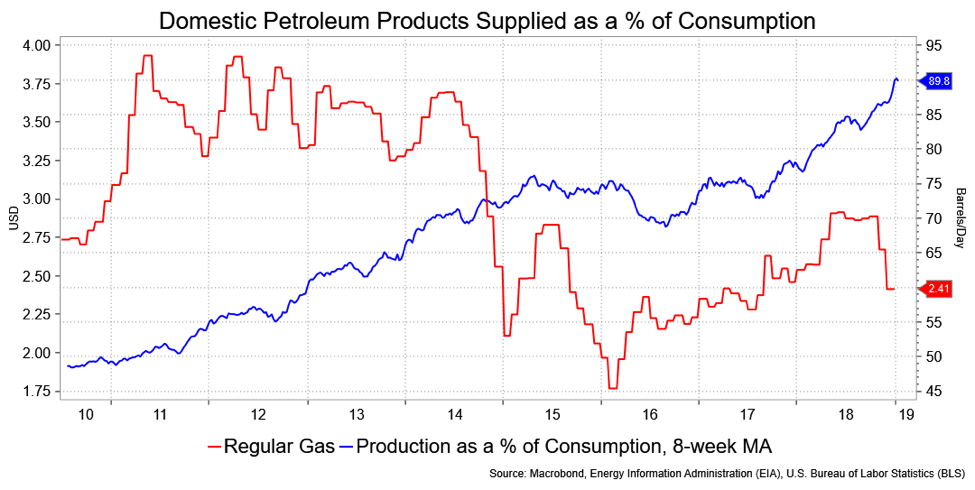

In many respects we’re the victims of our own success. Consider that the U.S. has increased domestic production of petroleum products sharply over the past 10 years. Just nine years ago, the U.S. produced less than half of its energy needs; the bulk of it was imported. Today about 90 percent of our energy needs are filled by domestic production.

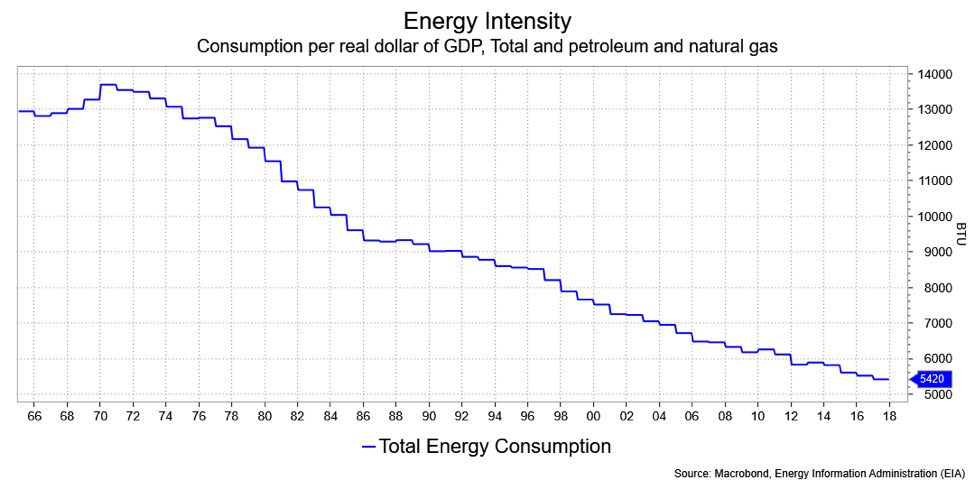

That’s a remarkable shift. The good news is increased energy independence and a revitalized domestic industry. But there is, for energy producers, a gray cloud to that silver lining. While the U.S. is producing vastly more of its own energy, we’re also using vastly less relative to our GDP. The concept is called energy intensity, which translates to our consumption in real terms (inflation adjusted) of energy for a dollar of GDP. In simpler terms, it’s the amount of energy we use for each dollar of GDP. Not only is the U.S. at the lowest level in over 50 years, but in magnitude we’re using 5,420 BTUs per dollar of GDP versus over 13,000 in the 1970s. As recently as 2000 we were at 7,520 BTUs.

The Energy Information Administration expects this trend to continue. They forecast energy intensity falling to 3329 BTUs by 2050. The same is true on a global basis. This doesn’t mean energy demand in aggregate will fall, just that we are a more efficient world.

What’s going on here? The biggest impact has unquestionably been the shift from an industrial economy to a service economy. Computers use rather less energy than, say, manufacturing plants. In our homes, despite low prices, there’s been a push for efficiency, using things like LED lights, more fuel-efficient appliances and better insulation.

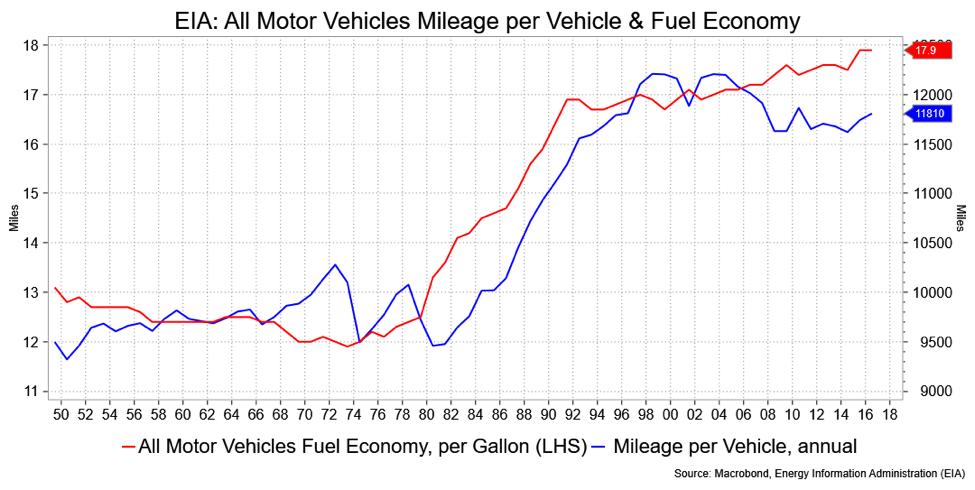

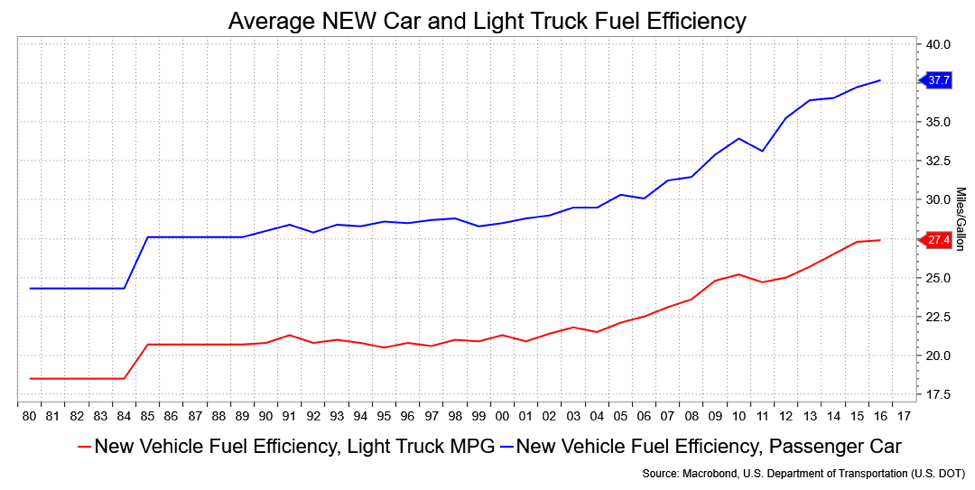

Another factor coming into play is fuel-efficient cars and trucks. Not only are our cars more economical, but we’re also driving less as well. According to the Department of Transportation, new passenger cars get an average of 37.7 miles per gallon as of 2016 and new light trucks just 27.4 mpg. Go back to 2000 and those figures were 28.5 mpg and 21.3 mpg, respectively. Overall car mileage (versus only new vehicles) stands at a near record 17.9 mpg and, given where new cars are coming in, will only rise over time. Meanwhile, we’re putting on 11,810 miles each year on average, a marked decline from the 1990s. This gets you thinking about electric cars, younger people staying in more urban locales, and aging suburbanites driving less, which, to play with words, extracts more fuel from the fire.

The flip side to that is that falling energy prices mean reduced expansion, if not contraction, in the energy industry. There’s an implication for the corporate bond market. The surge in BBB issuance these past 10 years (from 25 percent of the investment-grade bond market to nearly 50 percent today) has been highly influenced by issuance from energy companies. Should energy prices stay low, let alone slip, we could see a further degradation of credit quality in an investment-grade index, with the possibility a significant level of BBB-rated debt falls a few notches to junk. Investors relying on fixed income funds for income might be paying less at the pump, but that’s less likely to make them feel flush.

David Ader is the former chief macro strategist at Informa Financial Intelligence and previously held senior roles at CRT LLC and RBS/Greenwich Capital. He was the No. 1-ranked U.S. government bond strategist by Institutional Investor magazine for 11 years and was No. 1 in technical analysis for five years.