By Brian Chappatta

(Bloomberg Opinion) --It’s no secret that credit-rating companies took a significant hit to their reputations in the financial crisis, when they helped fuel a global housing bubble by awarding top grades to subprime mortgage investments. Perhaps anticipating another episode of too-lenient scoring, investors have been scrutinizing highly indebted U.S. companies rated in the lowest investment-grade tier.

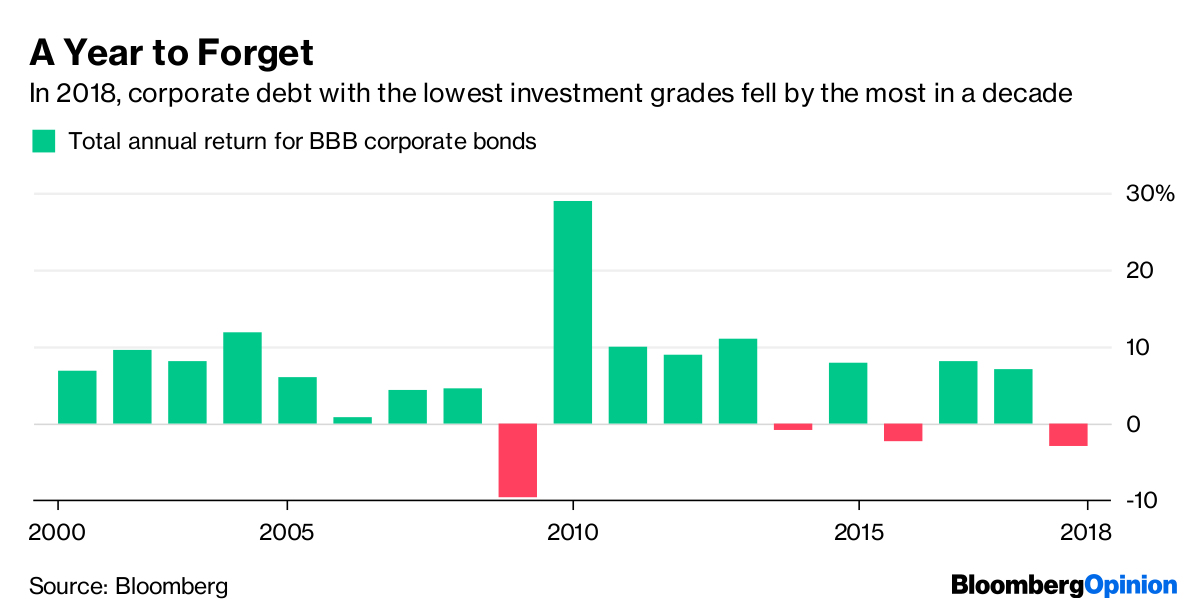

Their main concern is that a downturn would send those companies spiraling down the rating spectrum, creating a glut of junk bonds that could overwhelm the high-yield market and spark a widespread freeze in credit. After all, there’s now more than $2 trillion in triple-B debt, up from about $750 billion in 2007. With that doomsday scenario in mind, it’s little wonder those securities fell 2.9 percent last year, the biggest loss since 2008.

RELATED: Falling Angels and the Threat to Bond ETFs

Now Fitch Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service are pushing back on that narrative, with analysts laying out why their grades are sound and why the risk of a wave of “fallen angels” is overblown. Even for skeptical investors with memories of the financial crisis, these reports command attention, if for no other reason than credit raters can ill afford to be caught flat-footed again.

Essentially, their argument boils down to this: Many companies elected to go down this path. And while they’re highly indebted, corporate behemoths have other levers they can pull to stave off a downgrade to junk, even if the economy worsens.

Moody’s, for instance, provides a list of 20 companies it rates Baa (equivalent to BBB) with debt greater than four times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, and found that 15 of them added leverage for acquisitions. Analysts led by Kenneth Emery see those figures as temporary and expect almost all the companies to fall below the four-times threshold within the next year or two. Indeed, a recent JPMorgan Chase & Co. report found that debt-financed share repurchases at the end of last year fell to the lowest level since 2009 in one sign that the borrowing binge may be slowing down.

Fitch stresses that it “seeks to rate through cycles,” meaning that it focuses on an issuer’s willingness and ability to preserve its credit rating, even in a recession. It found that more than 90 percent of the companies it rates one or two steps above junk have a “financial flexibility” score that’s equal to or better than their overall grade. Simply put, Fitch argues that it would lower a company to speculative grade before a downturn if it couldn’t handle it, not during or after the fact.

Again, it’s hard to blame investors for being skeptical. I’ve written before about a phenomenon I call “superdowngrades,” in which a rating company lowers an issuer by three or more levels in one swoop. It doesn’t happen often, but is still a sign that the analysts are behind the curve at times. Already this year, PG&E Corp. is on the verge of becoming what Bank of America Corp. strategists call a “failing angel,” given its plans to enter bankruptcy as soon as this week (though private investment firms are offering a way to avoid that fate).

Still, PG&E’s situation is about as idiosyncratic as any in the corporate bond market. Moody’s insists “the vast majority of companies in the Baa category have sufficient strength to weather a recession without lasting damage to their financial or business profiles.” Note that says nothing about addressing an estimated $30 billion of liabilities tied to wildfires.

For those concerned that a ballooning BBB debt market means more borrowers will slip through the cracks, consider this: The number of companies Moody’s rates in the lowest investment-grade tier is up a mere 13 percent since 2007, to 297 from 262. In fact, the 20 largest companies account for almost half of the BBB debt outstanding. That includes household names like AT&T Inc., Verizon Communications Inc.. General Electric Co. and CVS Health Corp.

You could consider that concentration to be risky or reassuring, depending on your point of view. GE, for example, has had well-documented struggles, and putting the company on a healthier path will be difficult. At the same time, it’s still three steps above speculative grade because Moody’s considers the conglomerate’s size to be top tier and its business profile to be more in line with a double-A company. It’s reasonable to assume that Chief Executive Officer Larry Culp will tap into those strengths to avoid dropping into speculative grade and the headaches that would come with it.

Last year was an important one for credit markets because it forced investors to become more discerning. In November, I argued that there wouldn’t be a doomsday in BBB rated bonds because it seemed as if all of Wall Street was anticipating it. PG&E’s woes haven’t rattled the markets. The Federal Reserve has signaled it may ease up on its pace of interest-rate hikes, which, in theory, would leave the U.S. economy on stable footing with moderate growth. AT&T and CVS don’t need boom times to do just fine.

Maybe that makes me sound like just another Pollyanna of credit. Still, the fact that credit-rating companies seem to be doubling down on what’s causing some of the greatest angst in the corporate bond markets is something traders should consider. Because if they turn out to be right, it would put their financial crisis errors even further in the rear-view mirror.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit