Seventeen jurisdictions (or 34 percent of all states) in the United States now have domestic asset protection trust (DAPT) statutes.1 Some commentators originally thought that DAPT statutes would be limited to smaller populated states, but with Ohio entering the DAPT arena, the DAPT roster gained a populous state that’s also a major banking center. While the history of DAPTs is fairly recent in the United States beginning with Alaska in 1996,2 it’s anticipated that many more states will adopt DAPT statutes.

Since our last article on this topic in 2017 in Trusts & Estates, there’s been a fairly significant case relating to DAPTs. Moreover, the Uniform Voidable Transfer Act (UVTA) has been adopted by 18 states. We’ll therefore discuss both the recent case and the effect of the UVTA on DAPTs in more detail below.

DAPT Origins

A DAPT is a powerful tool to help clients legally shield assets from creditors, while at the same time permit them to be discretionary beneficiaries of their own trusts. However, recent cases demonstrate some limits on DAPTs’ effectiveness when residents from outside a DAPT state create a trust sited in a DAPT state. Further, if a non-DAPT state adopts the UVTA without modification, this will place significant additional limits on the use of DAPTs by residents of non-DAPT states.

Similar to our 2017 article, we again provide rankings of three different asset protection features behind these state laws: (1) discretionary support trust statutes; (2) anti-alter ego statutes; and (3) DAPT statutes (qualified disposition statutes).

To understand how these three types of statutes function, it’s important to know the history behind them. Common law discretionary trust protection originated under English law and isn’t related to spendthrift protection. Rather, discretionary trust protection is based on whether a beneficiary has an enforceable right to distributions3 and, therefore, whether a potential creditor might stand in the shoes of that beneficiary. If a beneficiary has no enforceable right, then the beneficiary’s interest isn’t a property interest4 and is nothing more than a mere expectancy that can’t be attached by a creditor.5

Discretionary Support Statutes

It’s the beneficiary’s lack of an enforceable right to compel distributions that provides the key concept to protecting against creditor claims, including the following types of marital claim issues:

1. Will the beneficiary’s trust interest be considered marital property subject to division in a divorce?;

2. Will an estranged spouse be able to force a distribution through a minor child beneficiary?; and

3. Will undistributed income be imputed by a court in the computation of a beneficiary’s child support or alimony?

A discretionary support statute is designed to codify the common law of the Restatement (Second) of Trusts (Restatement Second Trusts). Such statutes were enacted in response to the Restatement (Third) of Trusts (Restatement Third Trusts), which adopted a new and controversial view that drastically weakened common law discretionary trust protection.

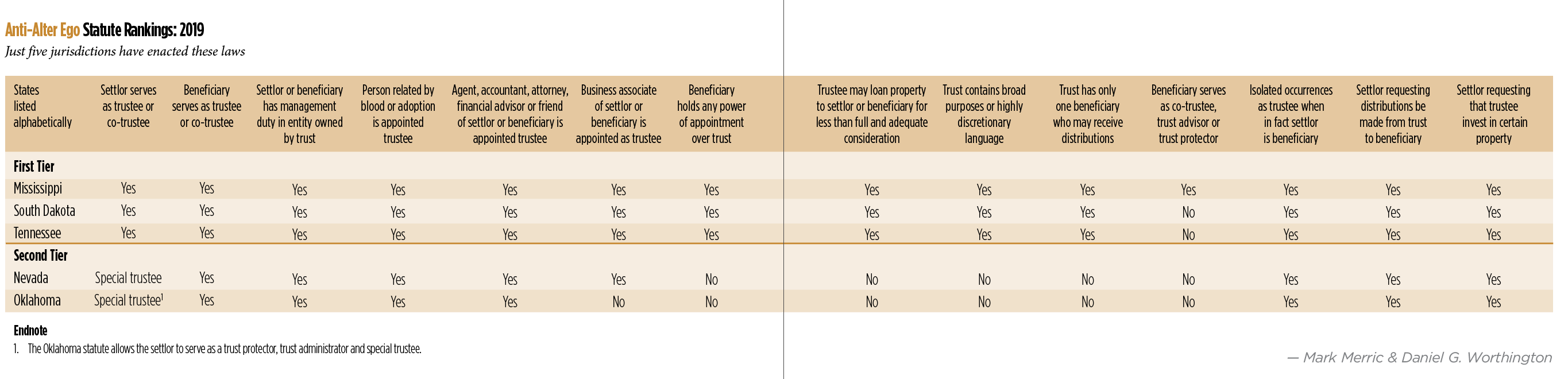

At the same time that South Dakota was the first state to codify discretionary support trust law, it and other states were also concerned with the rise of alter ego arguments (sometimes referred to as “dominion and control” arguments) that were being used to reach a beneficiary’s interest in a trust. Therefore, Mississippi, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Tennessee adopted statutes that protect against factors such as the settlor holding a removal/replacement power over the trustee, a trustee being a beneficiary, the settlor’s relationship to the trustee, as well as many others that suggest that the trust is the alter ego of either the trustee or a beneficiary.

As American common law developed from English trust law, it continued to respect discretionary trust protection. Conversely, spendthrift protection that developed under American trust law has generally been rejected by the English courts throughout the world. In general, a spendthrift clause prohibits a creditor from attaching a beneficiary’s interest and, in most states, also prohibits the beneficiary from selling the interest. When the first offshore statute was designed, it allowed use of spendthrift protections to shield a settlor/beneficiary’s trust interest. This concept has since been followed by almost all of the offshore asset protection and DAPT statutes.

However, DAPT statutes incorporated the American concept of exception creditors for items such as child support and maintenance—with one key difference. In U.S. trusts other than DAPTs, exception creditors apply only to support trusts, which give beneficiaries an enforceable right to distributions, whereas with DAPTs, exception creditors generally apply to both discretionary and support trusts.

The ability of an exception creditor to attach a discretionary trust interest in a DAPT is actually inconsistent with the common law definition of a discretionary trust. This inconsistency leads to a major weakness in a third-party trust should the drafter decide to include both the benefits and burdens of certain DAPT statutes as part of the protection of the third-party trust. It also highlights the need for many states to adopt anti-alter ego statutes.

Rankings

Here are our results when ranking DAPT statutes in these three categories: (1) discretionary support statutes; (2) anti-alter ego statutes; and (3) DAPT statutes (that is, qualified disposition statutes):

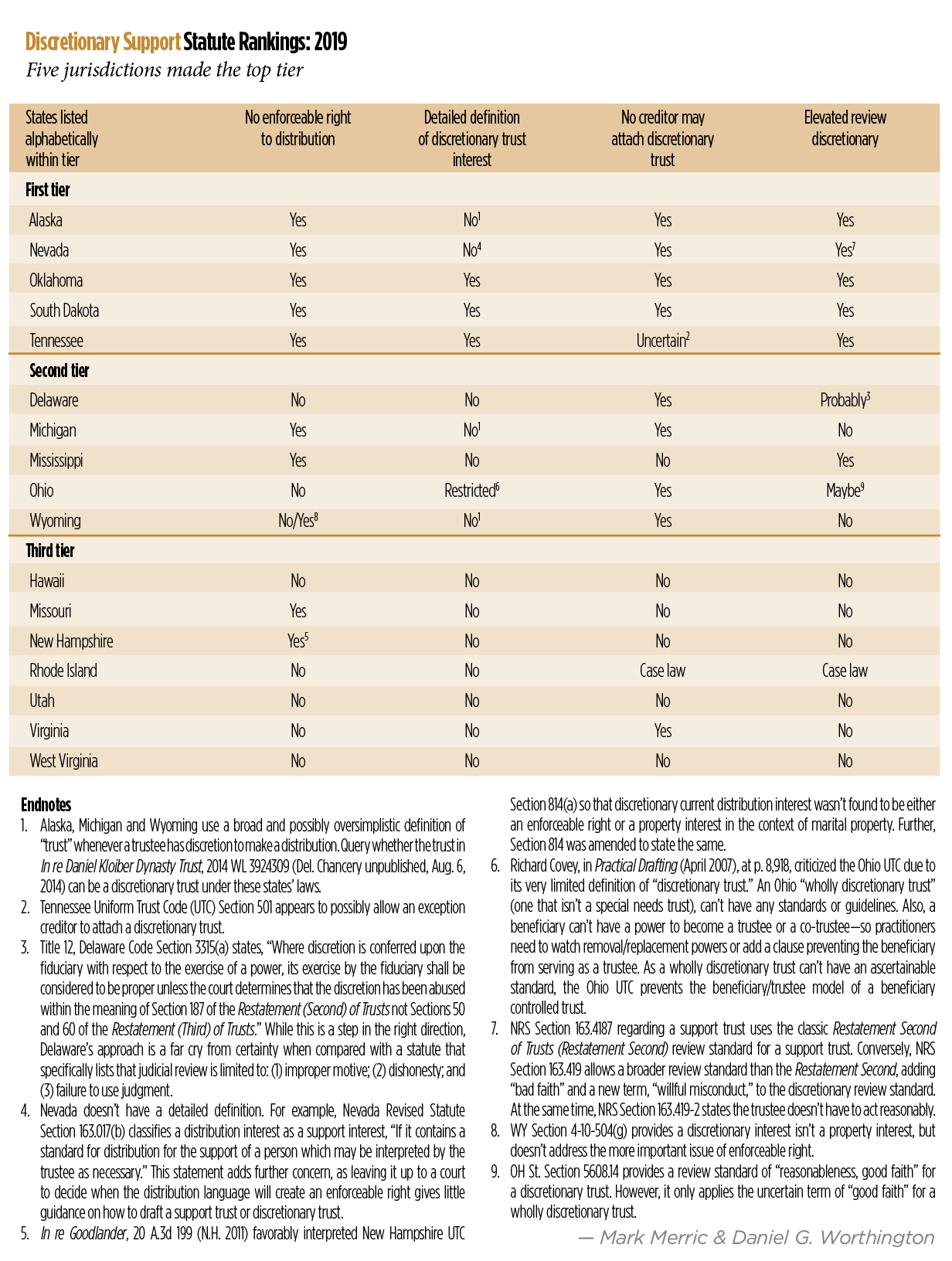

When ranking discretionary support statutes, the top tier is comprised of Alaska, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Tennessee. In the second tier, there’s Delaware, Michigan, Mississippi, Ohio and Wyoming. (See “Discretionary Support Statute Rankings: 2019,” p. 62.)

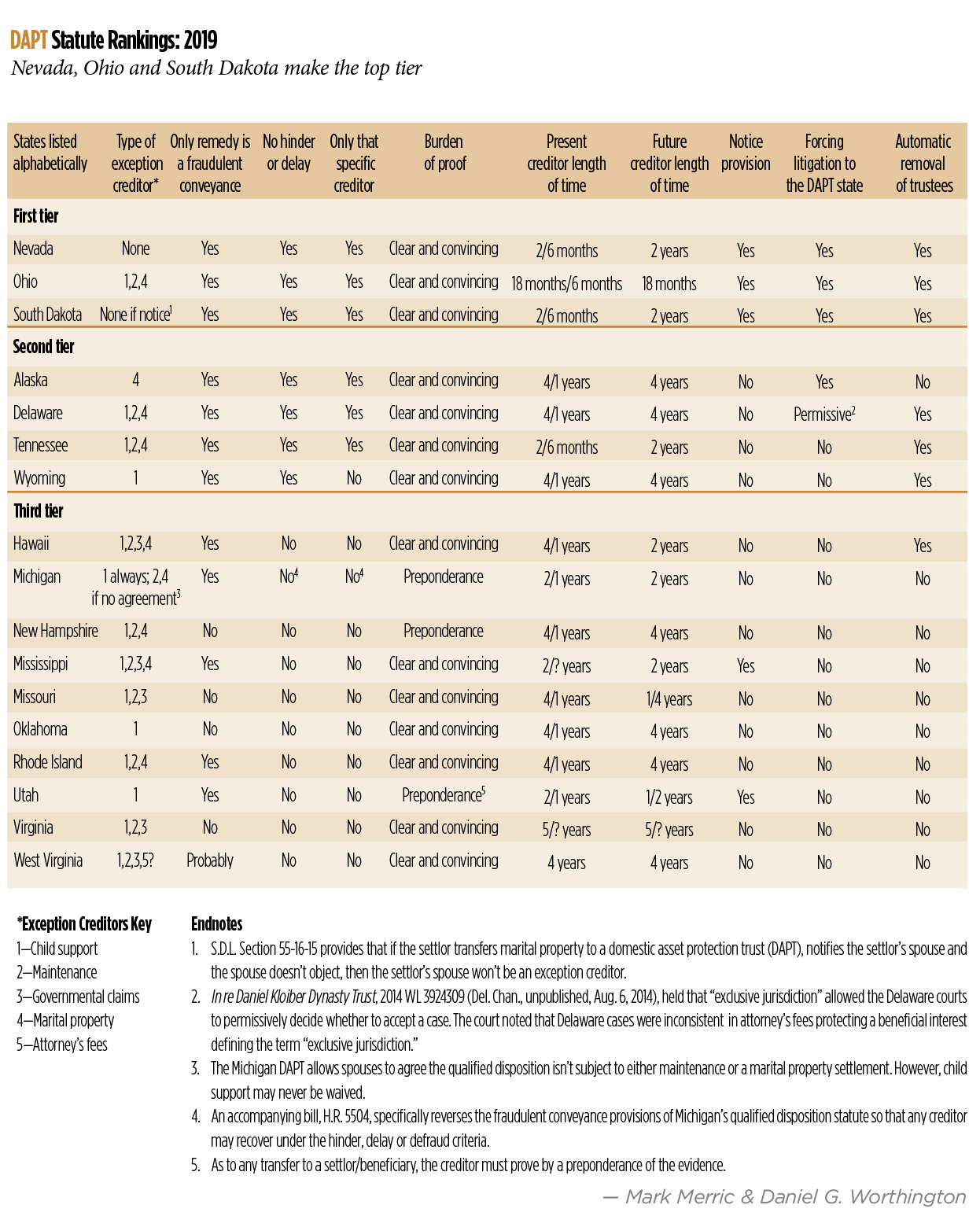

When ranking DAPT statutes (that is, qualified disposition statutes), the top tier includes Nevada, Ohio and South Dakota. The second tier includes Alaska, Delaware, Tennessee and Wyoming. (See “DAPT Statute Rankings: 2019,” p. 64.) While Nevada and South Dakota are very close, we note that Ohio most likely has the leading edge DAPT statute at this time. This point is further discussed in our analysis below.

When ranking anti-alter ego statutes, the top tier includes Mississippi, South Dakota and Tennessee. The second tier includes Nevada and Oklahoma. There’s no third tier, as the other DAPT states haven’t yet adopted anti-alter ego statutes. (See “Anti-Alter Ego Statute Rankings: 2019,” p. 66.)

Finally, we must consider the UVTA. While only two DAPT states have adopted this statute, its adoption absent modification by a DAPT state would be fairly fatal to any DAPT state seeking business from settlors who reside outside that state.

Toni 1 Trust

After the March 2, 2018 case Toni 1 Trust, by its Trustee, Donald Tangwall v. Barbara Wacker, et al.6 (Toni 1 Trust), a strong opponent of DAPTs proclaimed in a Forbes article, “Alaska Supreme Court Hammers Last Nail in DAPT Coffin for Use in Non-DAPT States.”7 However, to paraphrase Mark Twain, the reports of the DAPTs’ death have been greatly exaggerated. A closer look at Toni 1 Trust reveals why DAPTs are alive and well even in non-DAPT states. Further, when looking at DAPTs, it’s also important to address the proper timing of judicial actions as well as constitutional issues that emerge, such as the full faith and credit clause and conflict-of-laws issues. (See below.)

Toni 1 Trust was decided by summary judgment in favor of the defendants, William and Barbara Wacker and the bankruptcy trustee, all of whom sought to enforce fraudulent transfer judgments from a Montana state court and a federal bankruptcy court in connection with plaintiffs’ transfers to the Toni 1 Trust. Because it was a summary judgment decision, all factual allegations and inferences were construed in favor of the Toni 1 Trust, including the assumption that the trust was a valid Alaska DAPT. Among other things, the Wackers’ brief disputed that the Toni 1 Trust met the requirements of the Alaska DAPT statute and claimed that the trust was formed five years after a handwritten date of Dec. 20, 2010 on the trust document.8

Case facts. In 2007, Donald sued the Wackers in a Montana state court. The Wackers countersued Donald, his wife Barbara, his mother-in-law Margaret “Toni” Betran and nine entities the Wackers believed were Donald’s alter egos. In 2008, the court issued a judgment against the nine entities. In May 2011, the Wackers obtained two additional judgments against Donald, Barbara and Toni. Thereafter, one parcel of Montana real property was transferred by Toni to the Toni 1 Trust, and another parcel of Montana real property was transferred by Toni and Barbara. The warranty deeds were executed on Dec. 20, 2010.

Even though the Montana court assumed that the Toni 1 Trust was formed on Dec. 20, 2010, property was transferred to the Toni 1 Trust after judgments were rendered against the alleged alter ego entities and during the pendency of litigation. This raises serious fraudulent transfer issues. Also, after the judgments were rendered, Toni moved to Alaska and filed for bankruptcy.

The Wackers filed fraudulent transfer actions in a Montana state court as well as in the federal bankruptcy court. Both the Montana state court and the federal bankruptcy court found the transfers to the Alaska DAPT to be fraudulent. After these fraudulent transfer rulings, Donald, as trustee of the Alaska trust, filed for a declaratory judgment in Alaska, alleging that all judgments against the Toni 1 Trust from the Montana court were void and the statute of limitations barred future actions against the Toni 1 Trust. On summary judgment, the Alaska trial court ruled against the Toni 1 Trust, and the Alaska Supreme Court upheld this judgment.

Exclusive jurisdiction clauses. Ultimately, Toni 1 Trust9 deals with Alaska’s exclusive jurisdiction provision, which was the only issue that the appellants properly preserved for appeal. Similar exclusive jurisdiction provisions are found in a few other DAPT statutes. In our three previous DAPT articles in Trusts & Estates, we stated that “it was uncertain whether these provisions will survive a constitutional challenge.”10 As expected, the Alaska Supreme Court in Toni 1 Trust held that the exclusive jurisdiction provision in its DAPT statute was unconstitutional.

An exclusive jurisdiction clause in a state statute attempts to bar any other state (and possibly the federal government) from exercising jurisdiction over a matter subject to that clause. In Toni 1 Trust, the Alaska Supreme Court stated, “we have no doubt that the legislature’s purpose in enacting [this part of] that statute was to prevent other state and federal courts from exercising subject matter jurisdiction over fraudulent transfer actions against such trusts.”11 The constitutional issue was: Can one state prevent another state from exercising jurisdiction over matters crossing between states (that is, not lying exclusively within one state)?12 In Toni 1 Trust, this issue was significant because Montana had its fraudulent transfer law, whereas Alaska had a much more debtor-friendly fraudulent transfer law applicable to DAPTs. The Alaska Supreme Court held that the cause of action was transitory (that is, property was transferred from Montana to the Alaska trust), and therefore, the exclusive jurisdiction provision in the Alaska DAPT statute was unconstitutional under the U.S. Supreme Court case of Tenn. Coal, Iron, & R.R. Co. v. George.13

Knowing the specific issue the Alaska Supreme Court ruled on, as well as what wasn’t ruled on, helps to understand the narrow scope of the court’s opinion. The only issue that was decided by the Alaska Supreme Court was that the exclusive jurisdiction clause “cannot unilaterally deprive other state and federal courts of jurisdiction”14 on transitory actions. Moreover, the Toni 1 Trust appellants waived all other arguments on appeal, either because they failed to provide adequate legal authority (which amounts to a waiver under Alaska practice) or because they wholly failed to raise the issue.15 Of particular importance, the appellants’ brief didn’t discuss any choice-of-law issues.16 Conversely, the Wackers’ brief addressed conflict-of-laws issues and cited case authority.17 In any event, the Alaska Supreme Court’s discussion was essentially limited to the validity and effect of Alaska’s exclusive jurisdiction clause, and it left open for future case law many other issues related to full faith and credit and conflict-of-laws.

Timing. In addition to the appellants failing to bring up conflict-of-laws issues in their brief, the Toni 1 Trust declaratory judgment wasn’t filed at an optimal time. Under Article IV, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution, a sister state is required to render full faith and credit to judicial proceedings in another state.18 Under the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws (Restatement Second Conflicts), with certain exceptions, a “valid judgment rendered in one State of the United States must be recognized in a sister State.”19 Exceptions to this rule are made when one state claims that it has a strong public policy for not enforcing the judgment of a sister state. As stated above, in Toni 1 Trust, the conflict-of-laws issue and other defenses were waived.20

In future cases, it’s unknown whether Alaska courts, or any court in a DAPT state, will hold that a DAPT statute presents a strong public policy for not respecting a sister court’s fraudulent transfer judgment. However, from a tactical standpoint, the Toni 1 Trust appellants would have been in a much stronger position if the declaratory judgment had been filed in Alaska before the fraudulent conveyance action had begun in Montana. Had this been the case, and if Alaska had applied its fraudulent conveyance DAPT provisions, then the full faith and credit presumption may well have been reversed. It would then be up to a Montana court to decide whether Alaska’s DAPT fraudulent transfer law violated a strong public policy in Montana.

Best outcome? The Toni 1 Trust Alaska Supreme Court faced quite a dilemma. A Montana court, as well as the Alaska Federal Bankruptcy Court, had ruled that the transfers were fraudulent. Application of the federal full faith and credit clause was in favor of the Wackers. Further, there were many inconsistent facts involving the creation and validity of the Toni 1 Trust.21 For example, the defendants claimed that the trust was formed in 2010, but it contained a 2015 asset on its schedule of contributed assets. The following additional inconsistencies were alleged in the Wackers’ brief:

• On Dec. 20, 2012, Donald filed the adversary action in Toni’s bankruptcy. In this proceeding, he alleged in his complaint that the Toni 1 Trust was established in 1989.22

• At a hearing on June 5, 2013, the Bankruptcy Judge asked Donald about the trust, its formation and its beneficiaries. Donald replied that the trust was formed in 1996.23

Finally, but for the running of Alaska’s limitations period, the alleged facts of the Toni 1 Trust may well have resulted in a fraudulent transfer judgment even under Alaska’s more debtor-friendly statute. So, what were the Alaska Supreme Court’s possible options if it wanted to rule against the Toni 1 Trust? The worst result would have been to allow a conflict-of-laws analysis and then decide the case under the most significant relationship test, asserting that the transfer of property from Montana was the most significant relationship. As a result, the court would have applied Montana law for fraudulent conveyance purposes. Or, as the second worst result, the court could have used the full faith and credit clause and concluded that Alaska didn’t have sufficiently strong public policy grounds to apply its fraudulent transfer in ways that would supersede the prior Montana fraudulent transfer judgment.

Or, the court could have done exactly what it did, that is, reject the defendants’ exclusive jurisdiction argument. This left both the full faith and credit and conflict-of-laws issues open for another case on another day, hopefully with facts much more favorable to a debtor.

Questions remain. Citing the U.S. Supreme Court case of Marshall v. Marshall,24 the Alaska Supreme Court in Toni 1 Trust also ruled that a state statute’s exclusive jurisdiction clause couldn’t divest a federal court of its jurisdiction. The court correctly noted that such an argument would run afoul of the U.S. Constitution’s supremacy clause.

We’re also uncertain why Toni moved to Alaska and filed for bankruptcy. In bankruptcy, transfers to DAPTs are subject to the Bankruptcy Code’s 10-year look back rule, which is a very creditor-friendly limitations period. Further, in bankruptcy, a fraudulent transfer claim will succeed if a mere preponderance of evidence shows an intent to hin-der, delay or defraud creditors, whereas Alaska’s DAPT law requires a greater quantum of proof. Note also that it’s generally difficult for one creditor to file an involuntary bankruptcy on a debtor, and creditors are generally reluctant to start involuntaries. Consequently, Toni’s decision to voluntarily file for bankruptcy remains mystifying.

Hanson v. Denckla

Some DAPT proponents cite the U.S. Supreme Court case of Hanson v. Denckla25 as authority that, under conflict of laws, DAPT law should be applied. This case appears to be miscited. It’s true that the original Hanson Delaware and Florida cases were decided under conflict-of-laws principles, and the two states came to opposite conclusions over whose laws governed a revocable trust. Delaware held that a Delaware revocable trust was valid under Delaware law, while Florida held that the trust was against public policy under Florida law. It’s also true that conflict-of-laws arguments were raised before the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the Hanson Supreme Court ultimately decided the case on personal jurisdiction grounds and not under conflict-of-laws grounds.

In Hanson, a Delaware bank, as trustee of a revocable trust, never solicited any business in Florida by direct contact or mail, had no branch in Florida and didn’t transact any business in Florida. The Delaware bank also didn’t solicit business online (as there was no Internet in 1958). None of the revocable trust assets were located in Florida. Hence, the Supreme Court held that Florida didn’t have personal jurisdiction over the Delaware trustee because the trustee’s ties to Florida didn’t satisfy the sufficient minimum contacts test of International Shoe v. Washington.26 Today, with branch offices, seminars, mailers, webinars and use of the Internet to solicit out-of-state business, it may prove quite difficult for most DAPT companies to avoid personal jurisdiction outside of their home states.27

Conflict-of-Laws Standards

At this point, there’s little direct case law regarding exactly what factors and what weight a court will use to decide DAPT-related conflict-of-laws issues when creditors’ rights are involved either inside or outside of bankruptcy. Noted practitioners Gideon Rothschild, Jonathan G. Blattmachr and Daniel S. Rubin, in their seminal article, “Self-Settled Spendthrift Trusts: Should a Few Bad Apples Spoil the Bunch?”28 devote considerable discussion regarding trust conflict-of-laws issues, concluding that the governing law of a trust should control. The Restatement Second Conflicts generally holds that the law of a trust’s situs should govern. Unfortunately, the Uniform Trust Code (UTC) and the Restatement Third Trusts propose “the most significant relationship test” as the standard for deciding conflict of laws affecting trusts. While many commentators find this latter approach too subjective or unpredictable, some commentators argue that the most significant relationship test will generally cause the law of the trust’s situs to govern.29

We can thus make the following general statements:

1. It’s more likely that a judge from a non-DAPT state will apply the law of the DAPT state if most of the trust’s contacts are with the DAPT state.

2. The following factors are listed in order of importance:

(1) Governing law of the trust;

(2) Place of administration of the trust;

(3) Residence of the trustee;

(4) Location of the trust property;

(5) Residence of the settlor;

(6) Residence of the beneficiaries; and

(7) Any other factor.

It should be noted that the Kansas Appellate Court used a similar list of factors to determine the most “significant relationship” for purposes of conflict of laws under the UTC.30

Bad Facts Cases

Naturally, a judge in a divorce court (or any other court for that matter), who has virtually no knowledge of trust law and very little resources to get up to speed on the issues, could possibly find that a beneficiary or settlor living in that state is the most significant relationship and then apply the law of the beneficiary’s or settlor’s state. Of course, this type of ruling could be appealed. However, if a client actively participated in fraudulent activity and then funded a DAPT, there’s a good chance the court will ignore all conflict-of-laws principles and decide the case by applying the law most detrimental to the debtor.31

Planning Points

With Alaska’s exclusive jurisdiction provision statute being ruled unconstitutional in Toni 1 Trust, what should drafters of other DAPT statutes do to amend their statutes? Ohio’s DAPT provision provides a good jurisdictional solution that should result in Ohio courts ruling on declaratory actions regarding DAPTs within the confines of the U.S. Constitution as well as the Ohio Constitution. Ohio Rev. Code

Section 5816.10(H) states:

To the maximum extent permitted by the Ohio Constitution and the United States Constitution, the courts of this state shall exercise jurisdiction over any legacy trust or any qualified disposition and shall adjudicate any case or controversy brought before them regarding, arising out of, or related to, any legacy trust or any qualified disposition if that case or controversy is otherwise within the subject matter jurisdiction of the court. Subject to the Ohio Constitution and the United States Constitution, no court of this state shall dismiss or otherwise decline to adjudicate any case or controversy described in this division on the ground that a court of another jurisdiction has acquired or may acquire proper jurisdiction over, or may provide proper venue for, that case or controversy or the parties to the case or controversy. Nothing in this division shall be construed to do either of the following:

(1) Prohibit a transfer or other reassignment of any case or controversy from one court of this state to another court of this state;

(2) Expand or limit the subject matter jurisdiction of any court of this state.

Additionally, Ohio Rev. Code Section 5816.10(A) gives priority to Ohio’s DAPT statute in the event of any conflict between it and any other fraudulent transfer rules.

For these reasons and a few other minor issues, we find the Ohio DAPT statute to have a slight lead over the other top DAPT jurisdictions in the first tier of our rankings in “DAPT Statute Rankings: 2019.”

Impact on Alaska

Some commentators argue that, for purposes of DAPTs settled by persons who are non-residents of a DAPT state, Toni 1 Trust means that the fraudulent transfer law of a non-resident’s state will always take precedence over the DAPT state’s fraudulent transfer law. Some also argue that the Toni 1 Trust ruling affects only Alaska DAPTs and that the problem may well be resolved by settling a DAPT in another DAPT jurisdiction.

We disagree. The holding reached by the Alaska Supreme Court was narrow and could be well expected by any DAPT state with an exclusive jurisdiction provision. Given the limited scope of this ruling, many DAPT-related full faith and credit and conflict-of-laws issues are still up for grabs.

As to the odds of getting a better exclusive jurisdiction result in another DAPT state, that seems highly unlikely. The Toni 1 Trust ruling is well founded. Further, it’s not the first case to reject an unlimited claim of exclusive jurisdiction, as shown by the Delaware Chancery Court’s ruling in In Re Daniel Kloiber Dynasty Trust,32 which found that Delaware’s exclusive jurisdiction law could vest the Chancery Court with exclusive jurisdiction vis-à-vis other Delaware courts, but couldn’t deprive out-of-state courts of their jurisdiction. Consequently, any state with an exclusive jurisdiction clause is likely to meet a similar result.

Therefore, we find neither Kloiber Dynasty Trust nor Toni 1 Trust would be a significant factor weighing against either Alaska or Delaware as a lead DAPT jurisdiction, but only because all DAPT states with similar exclusive jurisdiction clauses will experience similar adverse results on this narrow question.

Klabacka v. Nelson

Klabacka v. Nelson33 is a recent marital dissolution case. Both the husband and wife executed separate property agreements with both parties having independent representation before signing the agreements. Both parties contributed their interests in the now-separate property to Nevada separate trusts that subsequently became self-settled spendthrift trusts under Nevada law. Among other things in the divorce action, the trial court issued an order that attached, for child support and alimony purposes, the husband’s beneficial interest in the self-settled trust that he created. However, the Nevada Supreme Court declined to allow the creation of an exception creditor for child support or alimony.

As not paying child support, and in some states, not paying maintenance, is a “go directly to jail” offense, we don’t find that preventing these exception creditors does much to enhance the asset protection of Nevada DAPTs for non-Nevada clients. Conversely, many times estate planners create a DAPT with the hope of excluding the DAPT from the settlor’s estate for estate tax purposes. In determining whether there’s an estate tax inclusion issue due to exception creditors, this is definitely a good case supporting Nevada DAPTs to be used for this purpose.34

UVTA Update

In 2014, The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws adopted the UVTA.35 It was intended to amend and replace the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act (UFTA) and differs from the UFTA in significant ways. Importantly, the UVTA fundamentally changes the treatment of transfers to DAPTs in states that have adopted it, especially with respect to creditors’ rights regarding transfers to DAPTs. This change should be of great concern to clients and practitioners alike. It’s our position that any state that has or is considering adopting the UVTA should either amend or exclude certain of its provisions to preserve DAPTs as an effective estate planning and asset protection technique.

One proponent of the UVTA has stated:

[T]he renaming should not be taken to imply that the UVTA is a new and different act, or that the amendments make major changes to the substance of the UFTA. Nothing could be further from the truth. The UVTA is not a new act; it is the UFTA, renamed and lightly amended.36

While this statement may be true in most other cases, it falls short of the mark where DAPTs are concerned. The most significant problems with the UVTA are associated with Sections 4 and 10 and their comments, wherein liberties were taken to make “voidable” legitimate transfers to DAPTs when a grantor resides in a state that’s adopted the UVTA with comments. The effect of the UVTA comments would be to possibly extend rights to creditors who were “neither existing or anticipated” by the grantor at the time of the transfer.37

Promoters of the UVTA praised it for removing the word “fraudulent” in favor of the more innocuous word “voidable,” thus clarifying for the public the misperception that a transfer had to include elements of fraud if one wishes to undo the transfer. By itself, that seemed to be an improvement over the UVTA’s less clear predecessor.

Voidable Transfers

However, intentional or not, the UVTA’s provisions and comments look to reach further than fraudulent transfers by potentially undermining legitimate transfers to DAPTs by settlors who reside in states where the law has been adopted. In such cases, these transfers to DAPTs become voidable.38

More specifically, gratuitous comments by the reporter of the Uniform Law Commission of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Law, in Section 4 of the UVTA, imply that such transfers to DAPTs are per se voidable. This position is contrary to most legal precedent on such questions and has been criticized broadly by practitioners and academics alike.39 In an attempt to allay these concerns, one promoter of the UVTA has suggested that, “The Comments, in short, are no more than a law journal article on steroids. The Comments … are not law, and courts are no more bound by them than they are by any other law journal article.”40 However, if that’s indeed the case, then why include the controversial comments at all? We believe that many have seen through the smoke and have elected not to include Section 10 and its comments in their state statutes. We find this approach to be most beneficial for those seeking to maintain the rights of citizens to protect their assets using the DAPT statutes.41

As stated above, the comments to UVTA Section 4 imply that transfers to DAPTs may be per se voidable. What’s the basis for this position? The comments only cite several older Pennsylvania cases that have been eroded over the years by subsequent decisions.42 Thus, the comments are no longer based in current generally accepted legal principles or cases. Note also that, even as old law, UVTA’s case cites are dubious: the Supreme Court in Schreyer v. Scott stated long ago that debtors are free to take steps to protect assets from creditors that were neither in existence prior to, nor reasonably anticipated at, the time of transfer.43

Further, a lack of DAPT legislation in a state, whether or not it’s adopted the UVTA, doesn’t necessar-ily create a presumption of a strong public policy against the laws of DAPT states. In a full faith and credit claim against a DAPT state trustee, the DAPT state shouldn’t be required to afford deference to another state’s statutes (including the UVTA) and is free to apply its own law, that is, its own DAPT statute. This is especially likely in cases involving post-judgment collection actions taken against the trustee of the DAPT in the DAPT jurisdiction.44

Note also that a fraudulent transfer judgment in a UFTA or UVTA state isn’t necessarily the end of the story. If assets are held in a DAPT state, then there remains a post-judgment collections issue. As alluded to by footnote 21 of Toni 1 Trust, and as explored in detail by other commentators, each state has a constitutional right to regulate and restrict the manner in which judgments are collected, provided that the rules apply to both in-state and out-of-state creditors, and the stringent fraudulent transfer standards of most DAPT statutes are just that: a restriction and regulation of post-judgment collections actions, which prevent any collection unless the creditor shows that the debtor violated those standards.45

Sufficient Contacts

UVTA Section 10, which encases the governing law provision, provides that, “a claim for relief … is governed by the law of the jurisdiction in which the debtor is located when the transfer is made, or the obligation is incurred,”46 ostensibly without regard to whether a different jurisdiction is chosen in a DAPT. This is a significant break from the traditional rule that a settlor can choose which state’s trust laws apply so long as there are sufficient contacts with the state.47

The “sufficient contacts” requirement was a major issue in a bad-facts case—In re Huber.48 The Huber court held that Washington, not Alaska, had the most significant relationship with an Alaska DAPT, and thus, Washington law applied. The settlor, a Washington resident, established an Alaska DAPT, which named an Alaskan corporate trustee in the DAPT state (Alaska) but named the settlor’s son, based in Washington, as co-trustee. The settlor’s son made frequent distributions to the settlor. This activity was one of the many factors that made the Alaska trustee look like a straw man. The Alaska trustee did very little. To support its ultimate conclusions, the Huber court cited to the Restatement Second Conflicts Section 270(a), which states that:

[t]he local law of the state designated by the settlor to govern the validity of the trust [governs], provided that this state has a substantial relation to the trust and that the application of its law does not violate a strong public policy of the state with which, as to the matter at issue, the trust has its most significant relationship.

Thus, where Washington had both a substantial relationship with Huber and a long-standing public policy position against self-settled DAPTs, the court “disregard[ed] the settlor’s choice of Alaska law, which is obviously more favorable to him, and [applied] Washington law in determining the Trustee’s claim regarding validity of the Trust.”49

Traditionally, in a conflict-of-laws analysis regarding a DAPT, a trust settlor can designate the laws that govern the trust so long as there are sufficient contacts with the state.50 However, the sufficient contacts requirement was a major issue in Huber. Additionally, Section 270(a) states that Section 273 applies so long as the law doesn’t violate a strong public policy of the state that has the most significant relationship to the trust. One of the ways that the UVTA attempts to thwart transfers to DAPTs is the application of Section 10, the governing law provision.

Debtor’s Location

UVTA Section 10 looks to a debtor’s location to determine which state’s laws apply for fraudulent transfer purposes. For individuals, this means the law of their home state applies, as UVTA Section 10 states that debtors are “located” in the state of their “principal residence.” However, this can create a conflict with DAPT laws. Specifically, while the UVTA doesn’t purport to affect the choice of trust laws, it does purport to affect the choice of governing fraudulent transfer law. In the context of DAPT statutes, UVTA Section 10 creates a potential overlap and conflict, as DAPT statutes have DAPT-specific fraudulent transfer laws that differ from the UVTA and that are more debtor-friendly than the UVTA and its dubious comments about self-settled trusts. Consequently, if a resident of a UVTA state makes a transfer to an out-of-state trustee in a DAPT state, and if the transfer is found to be fraudulent (or voidable) under the UVTA and its comments but is found to be valid under applicable DAPT standards, then there’ll be an inevitable conflict of laws. This conflict is sharpened because UVTA Section 10 and its comments effectively reject the right of another state to assert its interest and its laws in connection with a disputed transfer, regardless of which state has the most significant relationship to that transfer. Moreover, the UVTA’s comments even suggest that a true principal residence of a debtor in a DAPT state can be overlooked if a court concludes that a debtor’s residence is “notional,” “short term” or an act of “asset tourism.” That is, the UVTA comments actually invite courts to fish for reasons to ignore the UVTA’s own statutory rule giving priority to the laws of a settlor’s principal residence. As a result, individuals who in good faith move into a DAPT jurisdiction, settle a DAPT under that jurisdiction’s laws and then unexpectedly move out of that jurisdiction could have their DAPT judicially invalidated, even though the DAPT transaction occurred entirely within a DAPT state.

As before, it’s important to note that comments don’t have the force of law, and states can (and in the case of the UVTA should) revise the uniform law to suit their own situations if they even adopt it in the first place.

State Adoption

Thus far, 16 states have adopted the UVTA and comments in its entirety. They are: Alabama, California, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, Washington and West Virginia.51 An additional two states, Arkansas and Indiana,52 have adopted the UVTA, but not Section 10 and its comments. This is the course that other states that have adopted or choose to adopt the UVTA should take.53 Michigan and Utah are also DAPT states, which seems counter-productive. In total, five other states have considered adopting the UVTA but have not: Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island.54

In contrast, 17 states have adopted DAPT statutes, and an additional nine states have enacted statutory self-settled techniques, known as inter vivos qualified terminable interest trusts (QTIPs), which provide protection from creditors of the grantor.55 These are statutes that specifically abrogate the rule against self-settled spendthrift trusts for lifetime QTIP trusts. The nine non-DAPT states that have enacted these statutes are: Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina and Texas.56 In essence, these statutes provide that the assets of an inter vivos QTIP trust won’t be considered assets contributed by the settlor, even if the non-settlor spouse dies first and then leaves the same assets in further trust for the QTIP settlor.

Additionally, nine non-DAPT jurisdictions also have statutes that protect the assets in an irrevocable grantor trust from a creditor’s claim even though an independent trustee, in such trustee’s discretion, may reimburse the settlor for income tax resulting from assets in the trust.57

Finally, Arizona also protects the assets in a supplemental needs trust from a settlor’s creditors. As a result, the assets can’t be reached by creditors of the donor’s spouse after the death of the donee spouse.

Bottom Line

The fact that more than 29 states now have DAPT or DAPT-like statutes “moves this approach from the eccentric anomaly” category to an accepted and legitimate “asset protection and transfer tax minimization planning technique.”58 This trend undercuts the conclusion that these states have a public policy against a DAPT trust.

Similarly, enactment of asset protection for self-settled techniques such as inter vivos QTIP trusts, tax reimbursement provisions, supplemental needs trusts, Internal Revenue Code Section 529 accounts, individual retirement accounts (which are technically trusts), Employment Retirement Income Security Act plans (which are also trusts) and other self-settled techniques, bolster the argument that states with such laws don’t have a strong public policy against self-settled trust asset protection, and residents could form a DAPT under another state’s law. The same reasoning supports residents of DAPT states who use another DAPT state’s statute because of its superiority.59

In our view, and notwithstanding the UVTA, states should continue to follow the established rule of law, which is that a settlor may designate the law governing a trust unless it can be shown that:

1. trust situs and trust administrative ties to the relevant DAPT state aren’t substantial;60 and

2. creating a DAPT in a DAPT state violates a strong public policy of the settlor’s domicile state.

Unless both of these criteria are satisfied, the DAPT should generally be upheld,61 subject to any exception creditor rule,62 DAPT-specific fraudulent transfer rule or other exception provided by the governing DAPT statute.

We believe that states that are considering adopting the UVTA should beware of the difficulties that the UVTA potentially creates, and states that have already adopted the UVTA should consider amending or removing Section 4, Comment 2, and Section 10 and its comments.

Like any comparison of jurisdictions article, different authors will have different conclusions regarding what are the most important factors when evaluating a jurisdiction. Because about half of the U.S. population will experience at least one divorce, protection against marital claims is one of the most significant factors when evaluating the strength of a trust statute. The primary key to protecting against a marital claim may well be whether a beneficiary has an enforceable right to a distribution. This protection typically isn’t found in DAPT statutes but is instead found in the discretionary support legislation enacted by many states (or, in some instances, in state common law). Some of the more important DAPT protective features include limiting a creditor’s claim solely to a fraudulent conveyance, debtor-friendly fraudulent transfer law and forcing litigation into the DAPT state.

Endnotes

1. The 17 jurisdictions that have domestic asset protection trust (DAPT) statutes are: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming.

2. Prior to 1996, 18 nations had provided offshore APT statutes. While Missouri had amended its spendthrift trust statute in 1986 in a way that may have permitted the creation of a DAPT, the law lacked information about the intent of the statute and caused many concerns that the Missouri law wouldn’t prove to be an effective DAPT statute. See Richard G. Bacon, “The Domestic Asset Protection Trust at Five Years–Has its Time Arrived?” ALI-ABA course materials, Asset Protection Planning (Nov. 5, 2002), at p. 84. Also, note that Colorado hasn’t been listed on our chart, “DAPT Statute Rankings: 2019” at p. 64 as a DAPT jurisdiction due to case interpretation that severely questions whether Colorado’s 1800’s statute, C.R.S. Section 38-10-111, was ever intended for such a purpose. See In Re Cohen, 8, P.3d 429 (Colo. 1999) and In Re Bryan, 415 B.R. 454 (Bankr. D. Colo. 2009); contrast with In Re Baum, 22 F.3d 1014 (10th Cir. 1994).

3. Restatement (Second) of Trusts, Section 155(1) and comment (1) b.

4. In Mark Merric, “How to Draft Distribution Standards for Discretionary Dynasty Trusts—Part II,” Estate Planning Magazine (March 2009), endnote 41 lists cases from 16 states noting that a discretionary distribution interest isn’t a property interest.

5. Ibid.; Endnote 42 in ibid lists cases from 18 states noting discretionary interests couldn’t be attached at common law. Note that the Restatement (Third) of Trusts and the Uniform Trust Code (UTC) reverse common law in this area allowing a creditor to attach a discretionary interest. However, five UTC states have modified the national version of the UTC to retain common law in this area.

6. Toni 1 Trust by its Trustee, Donald Tangwall v. Barbara Wacker, et al., 413 P.3d 1199 (Ala. 2018).

7. Jay D. Adkisson, “Alaska Supreme Court Hammers Last Nail in DAPT Coffin for Use in Non-DAPT States in Toni 1 Trust,” Forbes (March 5, 2018), www.forbes.com/sites/jayadkisson/2018/03/05/alaska-supreme-court-hammers-last-nail-in-dapt-coffin-for-use-in-non-dapt-states-in-toni-1-trust/#af00fca62a77.

8. Toni 1 Trust v. Wacker, et al., Brief of Appellees Wackers, 2016 WL 7971969, at pp. 34-35 states that no settlor/beneficiary affidavit was executed as required by AS 34.40.110(j). There were a few inconsistent facts alleged in the Wackers’ brief that question whether the trust wasn’t formed until five years later after the handwritten date of Dec. 20, 2010.

9. See supra note 6.

10. Mark Merric and Daniel G. Worthington, “Best Jurisdictions Based on Three Types of Statutes,” Trusts & Estates (January 2017); Mark Merric and Daniel G. Worthington, “Find the Best Situs for Domestic Asset Protection Trusts,” Trusts & Estates (January 2015); and Mark Merric and Daniel G. Worthington, “Domestic Asset Protection Trusts,” Trusts & Estates (January 2013).

11. See supra note 6.

12. When cases discuss this issue, they usually refer to “transitory,” meaning that the transaction can occur in any state, as compared to a transaction that occurs only within the state that has the exclusive jurisdiction provision in its statute. We find it easier to understand the issue by using the term “transitory” to refer to a transaction between states, which is simply another way of stating the same thing.

13. Tenn. Coal, Iron, & R.R. Co. v. George, 233 U.S. 354 (1914). In this case, an employee sued his employer in a Georgia state court. The employer countered that Alabama state courts retained exclusive jurisdiction under Alabama law. The U.S. Supreme Court held that exclusive jurisdiction state law provision was unconstitutional.

14. See supra note 6, at p. 1201.

15. Ibid., at p. 1202.

16. Toni 1 Trust v. Wacker, et al., Brief of Appellant, 2016 WL 7971968.

17. See supra, note 8, at p. 35.

18. U.S. Constitution, Art. IV, Section 1.

19. Restatement (Second) Conflict of Laws (Restatement Second Conflicts) Section 93 (1971).

20. The Toni 1 Trust attempted to bring up the full faith and credit clause completely out of context, arguing that the full faith and credit clause resulted in Montana not having exclusive jurisdiction because the Alaska DAPT statute had an exclusive jurisdiction clause.

21. See supra note 8, at pp. 8, 9.

22. Ibid., at p. 11.

23. Ibid., at p. 9.

24. Marshall v. Marshall, 547 U.S. 293 (2006).

25. Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, reh’g denied, 358 U.S. 858 (1958).

26. International Shoe v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945). In his treatise, Commentary on Conflict of Laws (3rd Edition, the Foundation Press, Inc.), Russell Weintraub notes that, “Hanson v. Denckla was the first modern Supreme Court case to invalidate a state’s exercise of jurisdiction.”

27. For a somewhat contrary position, see Richard W. Nenno and John E. Sullivan III, “Delaware Asset Protection Trusts Create Obstacles for Creditors” (under obstacle # 3), Estate Planning Magazine (December 2005).

28. Gideon Rothschild, Jonathan G. Blattmachr and Daniel S. Rubin, “Self-Settled Spendthrift Trusts: Should a Few Bad Apples Spoil the Bunch?” 32 Vand. L. Rev. 763, 764 (1999).

29. See Nenno and Sullivan, supra note 27 (under obstacle #5).

30. Commerce Bank v. Bolander and Whittet, 2007 WL 1041760 (Kan. App. 2007) (unpublished).

31. In re Lawrence, 279 F.3d 1294 (11th Cir. 2002); In Re Portnoy, 201 BR 685 (Bankr. SDNY 1996); In Re Brooks, 217 BR 98 (Bankr. D. Conn. 1998).

32. In re Daniel Kloiber Dynasty Trust u/a/d December 20, 2002, 2014 WL 3924309 (Del. Chan. Aug. 6, 2014) (unpublished).

33. Klabacka v. Nelson, 394 P.3d 940 (Nev. 2017).

34. Mark Merric and Daniel G. Worthington, “Find the Best Situs for Domestic Asset Protection Trusts,” Trusts & Estates (January 2015).

35. Uniform Law Commission, Uniform Voidable Transactions Act (UVTA), www.uniformlaws.org/shared/docs/Fraudulent%20Transfer/2014_AUVTA_Final%20Act_2016mar8.pdf.

36. Kenneth C. Kettering, “The Uniform Voidable Transactions Act; or, the 2014 Amendments to the Uniform Fraudulent Transfer Act,” 70 The Business Lawyer 778 (Summer 2015), at p. 779.

37. Schreyer v. Scott, 134 U.S. 405, 414-415 (1890). The Supreme Court has held that individuals have a right to protect against future issues, stating, “Under such circumstances, the presumption of any fraudulent intent is rebutted, and it is manifest that he had done no more than any business man has a right to do, to provide against future misfortune when he is abundantly able to do so.”

38. See George D. Karibjanian, Gerald Wehle and Robert Lancaster, “A Memo to the States—The UVTA Is Flawed … So Fix It!!!” LISI Asset Protection Planning #367 (May 2018); Al W. King III, “Be Aware of the Uniform Voidable Transactions Act,” Trusts & Estates (October 2016); George D. Karibjanian, “The Uniform Voidable Transactions Act Will Affect Your Practice,” Trusts & Estates (May 2016); George D. Karibjanian, Gerald Wehle, Robert Lancaster and Michael A. Sneeringer, “New Uniform Voidable Transactions Act: Good for the Creditors’ Bar, But Bad for the Estate Planning Bar?” (Part Two) LISI Asset Protection Planning Newsletter #317 (March 15, 2016); George D. Karibjanian, Gerald Wehle and Robert Lancaster, “History Has Its Eyes on UVTA—A Response to Asset Protection Newsletter #319,” LISI Asset Protection Planning Newsletter #320 (April 18, 2016); Richard W. Nenno and Daniel S. Rubin, “Uniform Voidable Transfers Act: Are Transfers to Self-Settled Spendthrift Trusts by Settlors in Non-APT States Voidable Transfers Per Se?” LISI Asset Protection Planning Newsletter #327 (Aug. 15, 2016).

39. Ibid.

40. Karibjanian, Wehle and Lancaster, supra note 38, citing Professor Jay D. Adkins’ response to criticism of the UVTA comments.

41. Ibid. This article provides an excellent commentary on ways states should modify the UVTA.

42. See King, supra note 38; see also Section 4, Comment 2 of the UVTA, citing MacKason’s Appeal, 42 Pa. 330, 338-39 (1862); Ghormley v. Smith, 139 Pa. 584, 591 (1891); Patrick v. Smith, 2 Pa. Super. 113, 119 (Super. Ct. 1896).

43. Schreyer, supra note 37.

44. Note that if a DAPT jurisdiction adopts the UVTA and specifically includes Section 10 (Governing Law) and Section 4, Comment 2, this could prove problematic and possibly prevent legitimate wealth preservation planning using DAPTs in that state.

45. Ibid. See also Nenno and Sullivan, “Domestic Asset Protection Trusts,” BNA 868-1 TM (2010), at p. A-53 et seq.

46. UVTA, www.uniformlaws.org/shared/docs/Fraudulent%20transfer/2014_AUVTA_Final%20Act_2016mar8.pdf.

47. See King, supra note 38; Restatement Second Conflicts Sections 270 and 273 (1971); see also Riechers v. Riechers, 679 N.Y.S.2d 233 (June 30, 1998). In dictum, the Riechers court stated, “[a] cause of action would not lie to set aside the trust since the trust was established for the legitimate purpose of protecting family assets for the benefit of the Riechers family members.” The defendant-husband established an irrevocable trust in the Cook Islands, holding 99 percent of a Colorado limited partnership owning over $4 million of marital assets. The court held that it didn’t have jurisdiction over the corpus of the offshore trust, but nevertheless ruled that the trust assets were part of the marital estate and were subject to inclusion in the calculation of the total marital assets. See also Trust Co. Bank v. Susan M. Mathews, C.A. No. 8374-VCP, V.C. Parsons (Del. Ch. Jan. 22. 2015), in which a New York bank made a loan to a Florida limited liability company (LLC) with a personal guarantee by the defendant to construct self-storage facilities in Florida. The lender sued three Delaware DAPTs, contending that the defendant fraudulently transferred assets. The defendant claimed that the Delaware or Florida 4-year statute of limitations (SOL) should apply and not New York’s 6-year SOL. The court applied the 4-year Florida SOL and held that the plaintiffs’ fraudulent transfer claims were time-barred, finding that Florida and Delaware had more significant relationships than New York; Florida’s contacts included foreclosed real estate and business; and Delaware contacts included Delaware trusts and Delaware trustees. The court further held that if New York had been deemed to have a more significant relationship, then Delaware’s “borrowing statute” (which states if a cause of action arises outside of Delaware, then either the applicable Delaware limitations period applies or that of the state where the cause of action arose, whichever is shorter) would apply, and thus Delaware’s SOL would apply.

48. In re Huber, 201 B.R. 685 (Bankr. W.D. Wash. May 17, 2013). Additionally, an Alaska LLC (99 percent owned by the DAPT and 1 percent owned by the settlor’s son) held entities and real property located in Washington; the settlor’s son, based in Washington, was also the manager of the LLC. The case also featured fraud and bankruptcy issues and provides a useful lesson on how not to structure a DAPT to receive maximum situs protection and how not to administer a DAPT considering the substantial presence test of Restatement Second Conflicts Section 273.

49. Ibid.

50. See supra note 47.

51. See George D. Karibjanian, “American College of Trust and Estate Council State Law Status of the Uniform Voidable Transactions Act As of June 1, 2017,” in David G. Shaftel, editor, “Eleventh Annual ACTEC Comparison of the Domestic Asset Protection Trust Statutes,” www.actec.org/assets/1/6/Shaftel-Comparison-of-the-Domestic-Asset-Protection-Trust-Statutes.pdf.

52. Ibid.

53. See generally Karibjanian, Wehle and Lancaster, supra note 38.

54. See supra note 51.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid.

58. Ibid.

59. Ibid.

60. King, supra note 38.

61. Ibid. Creditors may argue that there was a fraudulent conveyance to the trust. For this claim to prevail, the creditor must prove that there was intent to hinder, delay or defraud a specific creditor. This argument, generally, is subject to a “clear and convincing” or “preponderance of the evidence” standard of proof, which varies depending on the DAPT state’s statute. There’s also an SOL for a fraudulent conveyance (usually two to four years), depending on state statute, after which time a cause of action or claim for relief with respect to a transfer of the settlor’s assets to a DAPT is extinguished, and the creditor may not be able to reach the assets. If the creditor is an existing creditor at the time the DAPT is established, that creditor may also have the period of time starting from when the creditor discovers or reasonably could have discovered the transfer to bring its claim (usually six months to a year), depending on state statute. Note that Nevada and South Dakota fraudulent conveyance periods are two years, and Alaska, Delaware, New Hampshire and Wyoming are four years. South Dakota and Nevada now have notice by publication statutes that begin the time at publication of notice instead of when reasonably discovered.

62. See King, supra note 38. A creditor may also claim to be an exception creditor, that is, the creditor fits within a defined type or class, so that it may be able to reach the DAPT assets. Exception creditors vary by state statute. Some of the more common are tort victims, divorcing spouses/marital property divisions and those receiving alimony or child support, and generally, any judgments in place at the time of the transfer regardless of state. It’s important to compare jurisdictions regarding the class of exception creditors.