By Nir Kaissar

(Bloomberg Opinion) --Socially responsible investing just received a big endorsement, but what it really needs is some clarity.

Yale University announced last week that its endowment might exit private investments it deems unethical, extending a policy it has long applied to investments in public markets. In fact, the university counts itself among SRI’s pioneers. Its ethical investment policy declares that “Yale was one of the first institutions to address formally the ethical responsibilities of institutional investors.”

Given the influence of Yale’s $29.4 billion endowment — second in size only to Harvard University’s $39.2 billion trove — the announcement will undoubtedly raise SRI’s profile. But SRI and the broader sustainable investing industry have never lacked attention. As my Bloomberg colleague Eric Balchunas recently pointed out, sustainable investing enjoys “to-die-for PR that eludes most categories.”

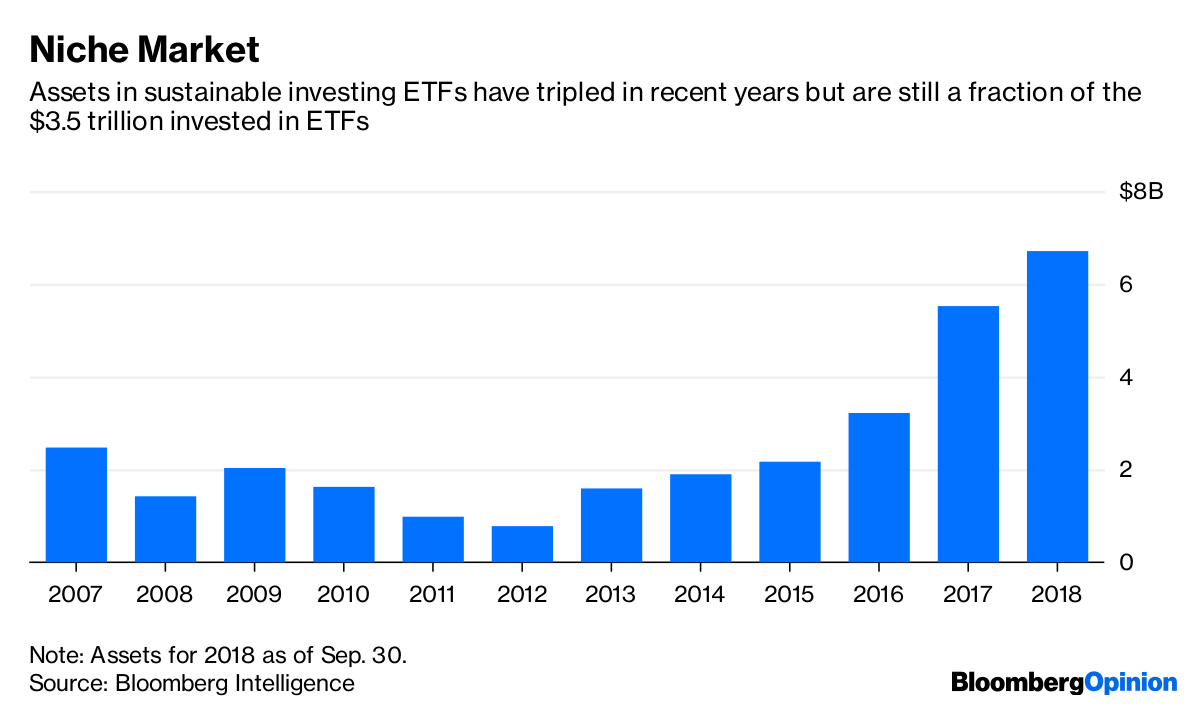

That attention hasn’t yet translated into investment, however, at least as judged by flows to exchange-traded funds. Just $6.6 billion of the $3.5 trillion in ETFs, or 0.2 percent, is invested in the category. Balchunas offers fund providers some sensible tips for sparking more interest, including lowering fees, choosing snazzier names, offering more concentrated portfolios and preaching to a broader audience.

But the industry has a more fundamental problem: Investors are lost among the various styles in the sustainable investing zoo. If the industry wants to attract investors, it must first explain what it has to offer.

For example, SRI and ESG, or environmental, social and governance, are two of the industry’s most recognizable acronyms. They’re often used interchangeably, but they represent distinctly different approaches.

SRI attempts to align investors’ portfolios with their values, mostly by excluding companies and sectors that don’t conform with those values. SRI funds commonly exclude firms in frowned-on businesses such as alcohol, tobacco and gambling, or those that contribute to greenhouse gas emissions or fail to comply with global norms and conventions.

Importantly, SRI doesn’t make any promises about the impact of those exclusions on investors’ portfolios, but it’s reasonable to expect that investors will pay a price. After all, the point of SRI is to make money scarcer for undesirable companies, which would require them to pay more for capital. By the same logic, desirable companies should pay less.

That squares with the recent experience of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, an early adopter of ethical investing. Its manager, Norges Bank Investment Management, reported last year that the fund's stocks trailed the FTSE Global All Cap Index by 1.1 percentage points annually over 11 years through 2016 because of exclusions on ethical grounds.

ESG, on the other hand, is a completely different animal. It attempts to identify environmental, social and governance policies that, in back tests, have translated into less volatility and higher risk-adjusted returns for stocks of companies that adopted those policies. The idea is that sound ESG policies reduce companies’ exposure to risk, which should then be reflected in their stock prices. In that regard, ESG investing is more akin to factor investing strategies such as value and momentum than SRI.

There isn’t perfect agreement around those definitions of SRI and ESG, which is a further source of confusion. It also doesn’t help that sustainable investing has a short track record, and that early results don’t jibe with the industry’s claims.

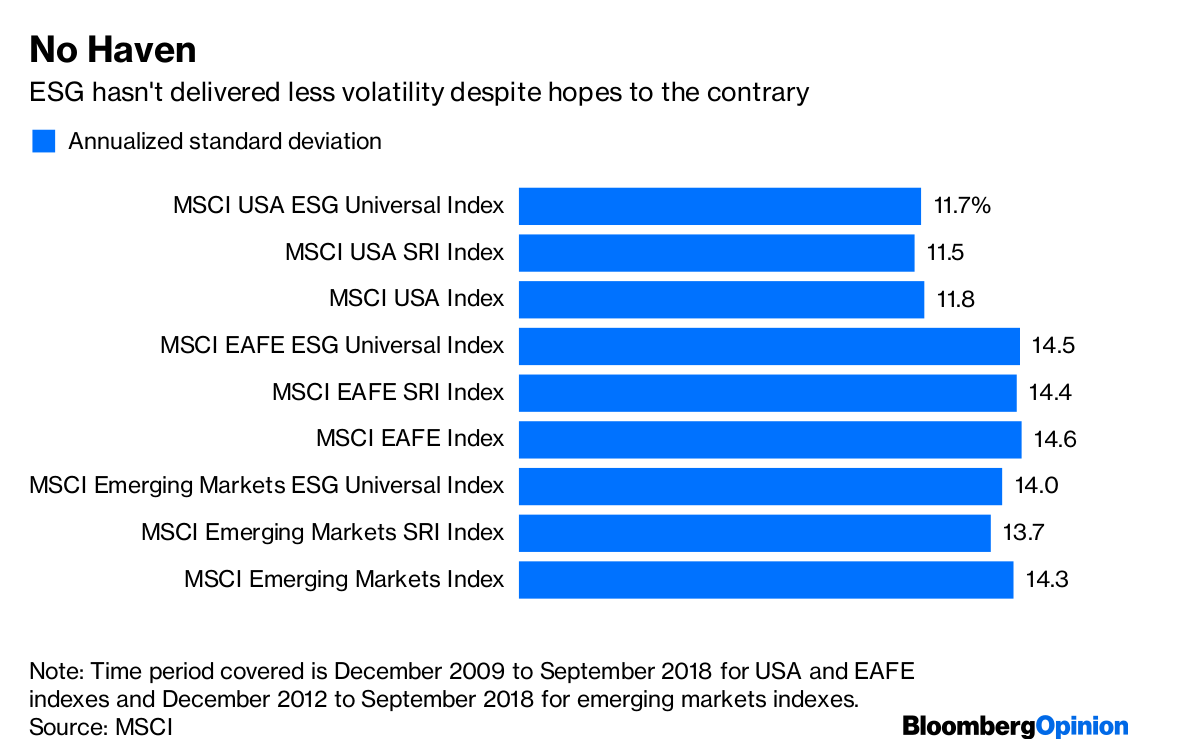

ESG, for example, hasn’t delivered a smoother ride than SRI or the broader stock market. The volatility of the MSCI USA ESG Universal Index was nearly identical to that of the MSCI USA SRI Index and the MSCI USA Index from December 2009 through September, the longest period for which numbers are available for all three. The same was true for comparable developed international indexes over that period, and for emerging market ones since December 2012.

Nor has ESG delivered higher returns after accounting for risk. The Sharpe Ratio — a common measure of risk-adjusted return — was nearly identical for all three USA indexes. And the Sharpe Ratios of the SRI indexes in developed international and emerging markets were higher than those of the comparable ESG indexes.

And that’s just the beginning. There’s a growing list of sustainable investing approaches, some of which are subsets of SRI and ESG and others that are separate schools. Interest in sustainable investing will most likely continue to grow. It would help if investors understood what they were buying.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

To contact the author of this story: Nir Kaissar at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view