By Natasha Doff

(Bloomberg) --Plenty of investors are still willing to pay extra to have humans look after their wealth.

Just ask Garth Taljard, who runs 50 multi-asset funds for Schroders Plc, the U.K.’s biggest asset manager. As mutual funds lost more than $300 billion in the U.S. since 2014 amid the rush into cheaper passive funds that mimic indexes, he was hiring to keep up with demand that doubled over five years.

“Investors realize it’s quite challenging for themselves to do asset allocation, it’s very much a full-time job,” said Taljard, who added two new money managers this year to a global team of 85, responsible for divvying up 64 billion pounds ($80 billion) of clients’ cash.

Funds like his haven’t suffered the same fate as other active portfolios because they offer something that isn’t easy to automate: a one-stop-shop where risk-averse insurers or pension funds can spread money across assets as diverse as U.S. blue-chip stocks and emerging-market currencies.

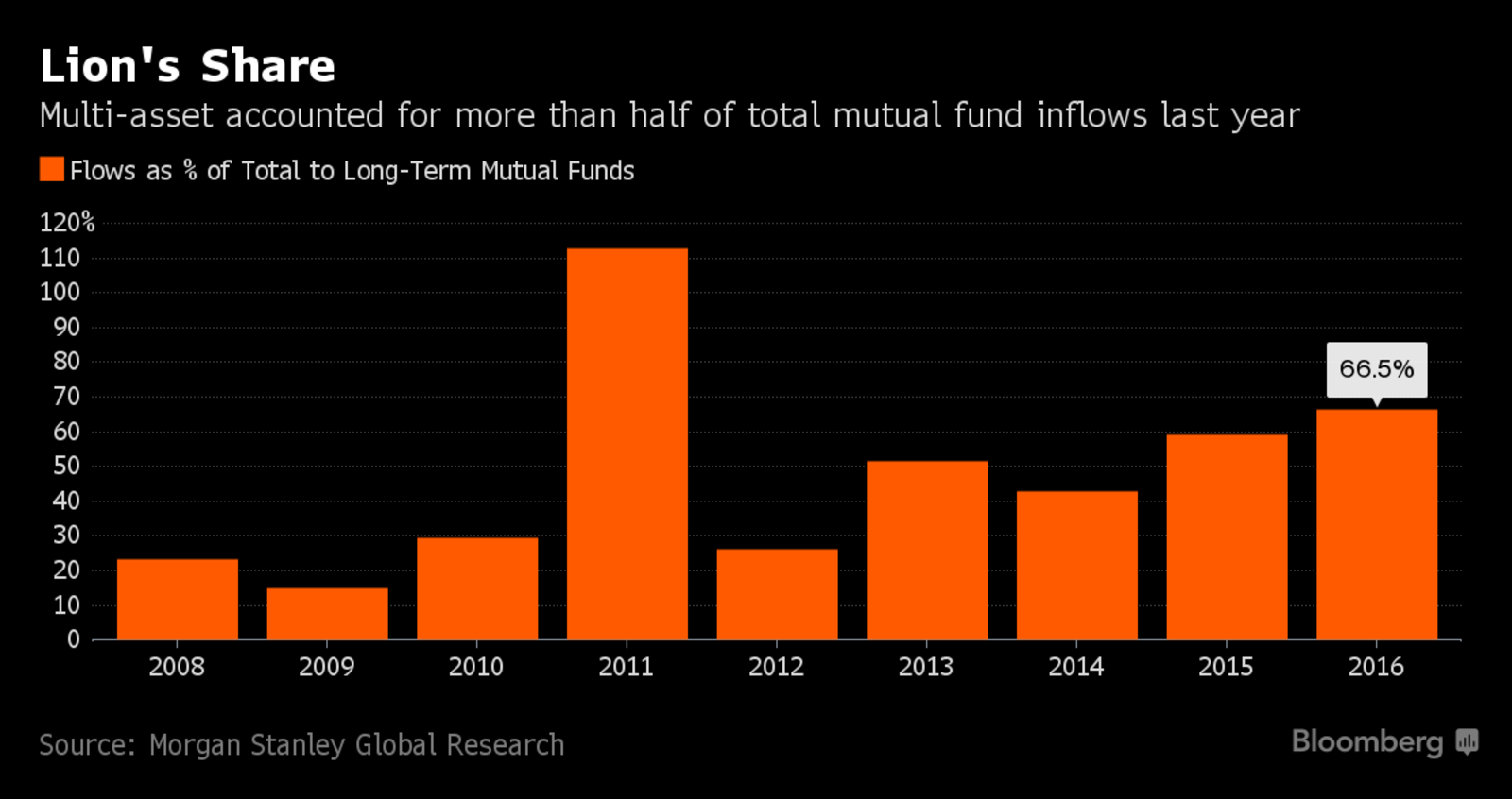

This strategy gained popularity after the global financial crisis -- Morgan Stanley says $2 trillion flooded into multi-asset funds since then -- because investors wanted to shield their wealth from future market shocks. Political turbulence from the election of Donald Trump and the rise of European anti-euro parties will only fuel demand.

While the funds generate lower returns, their managers can hedge against unforeseen turmoil by quickly moving into safer assets and reverting to riskier ones once things settle down. That versatility comes with a fee more than double that on exchange-traded funds, according to industry data provider Morningstar Inc.

“Investors are looking for active multi-asset managers to help navigate potentially troubled waters ahead,” said Taljard, who moved to London last year from Hong Kong, where he oversaw Schroders’ Asian multi-asset business.

ETF Dominance

As managers like him thrive, traditional mutual funds have, by and large, lost out to ETFs, especially in the U.S. Known as passive funds because their managers don’t actively pick individual securities to buy and sell, ETFs charge on average about 10 basis points and routinely beat their active counterparts. They’ve fetched $2.8 trillion of inflows since 2008, almost half in just the past three years, Morningstar data show.

But there’s a catch: passive funds are easy to enter and exit and thus attract a lot of the speculative money that flees quickly in a market rout.

Pension funds and insurers are limited by how much they can expose their customers’ retirement savings to risks. After the 2008 crash, Europe slapped rules dubbed Solvency II on insurers, for instance, to guarantee their business models are safe enough to ride out a severe financial shock.

This is where multi-asset managers carved out a niche. Years of near-zero and negative interest rates in the industrialized world made it impossible for institutions to keep relying on bond funds for wealth preservation.

Instead of trying to build their own complex investment portfolios to generate steady returns, many handed the reins to the likes of Schroders and JPMorgan Chase & Co., whose assets under management quadrupled in the five years through December to $199 billion.

Multi-asset managers broadened their mandates beyond equities and fixed-income, and analyze factors like valuation, carry and momentum when allocating funds. They also invest across countries and industries, including in ETFs, helping them secure a new captive audience.

“Some types of investors felt after the financial crisis that asset allocation is very challenging and it’s good to get help,” said Olivia Mayell, a fund manager at JPMorgan Asset Management in London.

Future appetite for these strategies depends, to some extent, on whether the normalization of U.S. and European monetary policy starts to draw people back to traditional low-risk investments, like bonds.

Missed Opportunity

For the downside protection, investors in multi-asset funds have also missed out on a whole lot of upside. A stock-market rally handed investors in the S&P 500 about 70 percent in five years, while a Bank of America Merrill Lynch global bond index returned 17 percent.

The performance may not be enough to turn the tide. While more expensive than ETFs, the 1.02 percent median fee on European multi-asset funds is about half the cost of typical hedge funds, and pressure to reduce fees is only building.

“To some extent the multi-asset fund is giving you a little bit of what the fund of hedge funds gave you in the past, in terms of equity-like returns but with lower risk,” said Randal Goldsmith, a senior analyst at Morningstar in London.

Geopolitical turmoil is also a boon for multi-asset strategies, according to Michael Cyprys, an asset-management analyst at Morgan Stanley in New York. Investors want “downside protection” against shocks and are more inclined to seek outcomes -- like capital preservation or inflation protection -- than high returns, he said.

Le Pen Risk

One such blow would be if anti-euro nationalist Marine Le Pen wins French presidential elections next month, sending the euro tumbling 10 percent if JPMorgan predictions are right, and triggering a 23 percent drop in the Euro Stoxx 50, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch projections.

The loss for a multi-asset fund that counterbalances European holdings with haven assets like the Japanese yen? About 4 percent, says Legal & General Investment Management’s London-based head, John Roe, who’s AUM swelled from 1 billion pounds to 15 billion in four years.

Back at Schroders, Taljard said although demand remains high, asset managers are vying for contracts with clients who increasingly want to keep running their own funds, but with a hand from the industry.

“Instead of just giving us a mandate to manage they also want to learn and share ideas with us,” he said. “Schroders has grown its assets, but we’ve also seen a lot more competition.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Natasha Doff in London at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Samuel Potter at [email protected] Daliah Merzaban, Cecile Gutscher