By Barry Ritholtz

(Bloomberg View) --The front page of yesterday’s Wall Street Journal called out mutual-fund analytics firm Morningstar and its five-star rating system.

The Journal’s conclusion? Top-rated funds “drew the vast majority of investor dollars, but most didn’t continue performing at that level.” Morningstar, of course, said “its ratings were not supposed to be predictive and they should be a starting point for investors selecting funds.”

Mean reversion aside, that misses the point of what Morningstar is, and how it is supposed to be used. To be fair, the same can be easily said about the Wall Street Journal, or for that matter, Bloomberg View, or just about another outlet for financial news and information. Securities firms develop analytical models, writers craft columns, analysts analyze, any or all of which are subject to misuse by the investing public.

Retail and professional investor alike seem to ignore the fact that every single document ever generated by any investment-related firm has a warning on it to the effect that “Past performance is not an indicator of future returns.” Every chart ever drawn, each investing idea back-tested and every single historical comparison is testament to how little mind humans pay to that disclaimer.

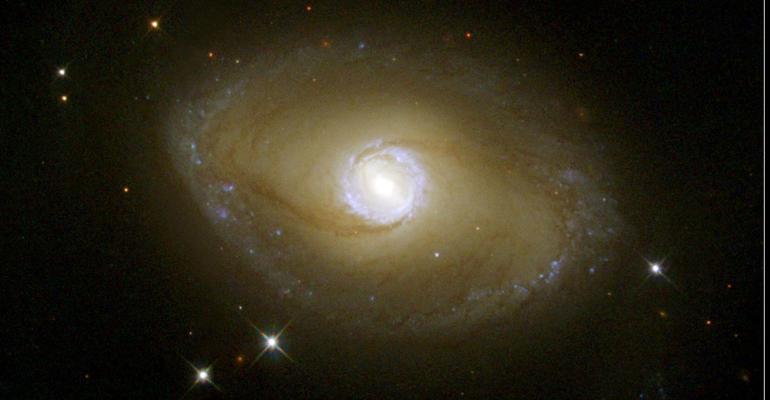

To borrow from and paraphrase the Bard, the fault lies not in the stars, but in ourselves.Thus, it should come as no surprise that misunderstanding what fund ratings mean is a very typical error made by, well, just about everyone. It isn't a forecast of future returns, nor could it be. If it could successfully do that, Morningstar would have long ago set up a hedge fund to profit from its newly discovered abilities to identify winning investments.

The star-ratings shortcomings as a forecaster of future returns was obvious as I noted back in 2012:

The Morningstar mutual fund rating 5-star ranking attracts lots of new investors and lots fresh dollars. The primary factor in the rating is (can you believe it?) past performance. This despite a Morningstar study that found 5 star funds mostly underperform — my assumption is it’s a case of simple mean reversion. As it turns out, the fund’s expense ratio is a much better predictor of performance (See results here).

When making any investment, make sure you are not merely chasing a hot quarter or two. Note that there are 10,000 hedge funds and 12,000 mutual funds and very few consistent managers generating sustainable, repeatable returns.

The Journal went into much more detail than I did, and developed a methodology for grading the star-rating system. But its conclusion was more or less the same.

Whatever the criticism of Morningstar might be, however, let's acknowledge that it is a great resource for anyone trying to hunt down basic information on mutual funds. The Journal does a nice job of telling the story of how Morningstar founder Joe Mansueto created the fund-ratings business. What might be lost in that tale is how little publicly available data existed about mutual funds before Morningstar was started.

As for the star-rating system: I have never used it as the basis for making an investing decision. Although my role is rather different from that of the average retail investor, our ability to foresee the future is the same -- negligible.

To Morningstar’s credit, it has run articles repeatedly over the years indicating that fund expense ratios and costs are a better predictor of future returns than its star ratings. In 2010, Morningstar's Russel Kinnel made this exact point: “If there's anything in the whole world of mutual funds that you can take to the bank, it's that expense ratios help you make a better decision. In every single time period and data point tested, low-cost funds beat high-cost funds.” He updated that theme last year, emphasizing that costs are a determinative factor.

I can think of more than a few firms that would have spiked or buried research that essentially undercut its main product. To Morningstar’s credit, it did not.

Nonetheless, the five-star ratings do exert a powerful gravitational pull. They are comforting and confirming and give a buyer cover for a decision that is statistically likely to not turn out so well.

But here’s the thing: That’s the exact reason one should never consider it in the selection process. It serves as an emotional salve that's obviously based on past performance. There's nothing wrong for an investor to know about that history. It's just that it shouldn't play a role in determining investments made today.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Barry Ritholtz is a Bloomberg View columnist. He founded Ritholtz Wealth Management and was chief executive and director of equity research at FusionIQ, a quantitative research firm. He blogs at the Big Picture and is the author of “Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corrupted Wall Street and Shook the World Economy.”

To contact the author of this story: Barry Ritholtz at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view