By Brian Chappatta

(Bloomberg Opinion) --As far as analogies go in the financial markets, this one from Moody’s Investors Service is brutal: Active mutual funds are to landlines as passive funds are to mobile phones.

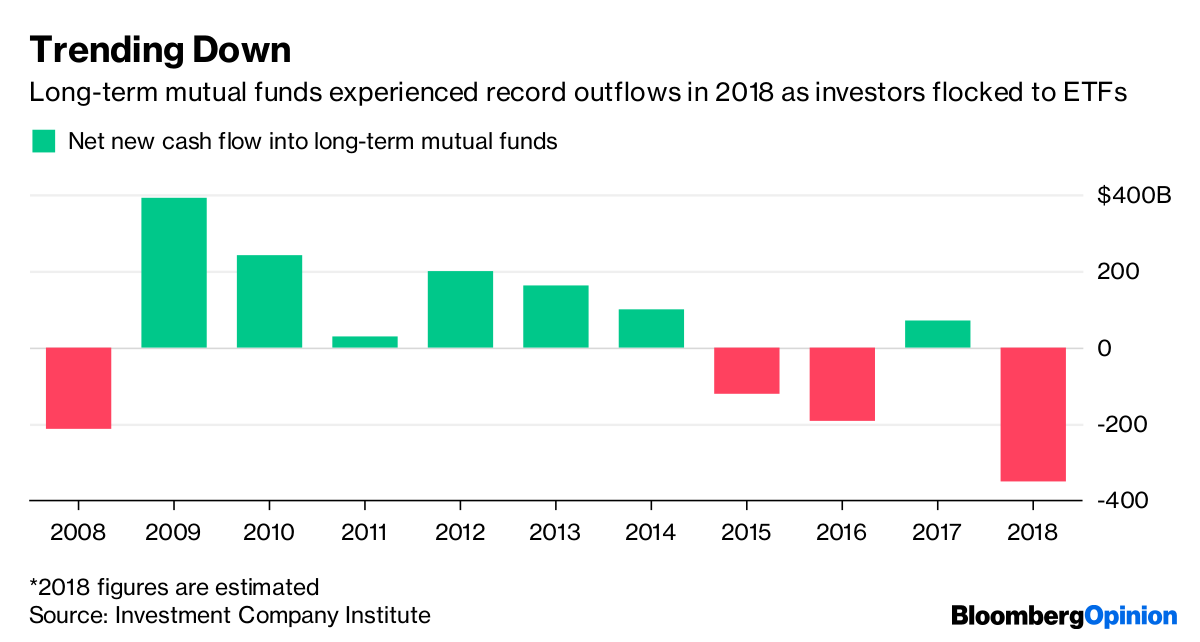

That’s the takeaway from analysts led by Stephen Tu after seeing a record $369 billion pour out of long-term mutual funds in 2018, while flows into exchange-traded funds remained largely in line with recent years. That stark difference, Moody’s says, is “credit negative” for traditional asset managers and may “indicate a loss of relevance with clients.”

Call it the Jack Bogle effect. The Vanguard Group founder, who died this week at age 89, has received praise across Wall Street for transforming the world of investing by focusing on low-cost products that has shifted money from fund managers to individuals. It’s only fitting that the Moody’s report was released less than 24 hours after the news of his death — it might as well have been a final tribute to the pioneer of low-cost indexing:

“Passive flows are best thought of as akin to the adoption of a value-additive technology (cell phones vs. landlines, for example), and will steadily diffuse throughout the marketplace over time. Passive, low-cost funds are a more efficient vehicle to channel the earnings from corporate America to the end retail investor because there is less leakage of earnings from investment management fees to asset managers, trading costs to brokerages and other intermediaries, and investment activity and errors on the part of average active managers to the small number of truly superior active managers. As a result, the underlying driver of flows into low-fee passive funds over higher-fee active funds is changing consumer preferences as a result of greater transparency.”

There’s no sugarcoating it: This is a grim outlook for active fund managers. Effectively, Moody’s is saying that there’s no direction the markets can move that will help them bring in more money because investors have taken to heart the idea that low-fee, passive vehicles will outperform (or at least remain very competitive) in the long run. Just as millennials dismiss landline phones as obsolete in the smartphone era, so, too, will the current generation abandon funds that contend they can consistently beat their benchmarks. Moody’s has said it expects passive to overtake active strategies no later than 2024.

The writing has been on the wall. In June, I argued that a Moody’s downgrade of Franklin Resources Inc. — its first rating cut of a single-A asset manager in five years — raises the stakes for the investors who still brand themselves as market luminaries.To be clear, active managers aren’t throwing in the towel. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Nir Kaissar, for instance, noted that Jeffrey Vinik, who rose to fame as manager of the Fidelity Magellan Fund in the 1990s, is getting back into stock picking. Bill Gross appears to be employing a merger-arbitrage strategy in his Janus Henderson Global Unconstrained Bond Fund, which might have helped stem earlier losses. At Franklin, Michael Hasenstab’s Templeton Global Bond Fund is up 2.4 percent over the past year, compared with a loss of 1.3 percent for his benchmark.

But many of the long-standing arguments for active management seem to no longer apply. For one, turbulent markets are supposed to be the time for stock and bond pickers to earn their keep, using dislocations to buy and sell at fleeting and favorable prices. That didn’t really happen, though the persistent outflows likely made it harder to swoop in. On top of that, 2018 put to rest the idea that passive funds are only appealing for highly liquid markets, like U.S. equities. In fact, a sharp move out of active bond funds is what exacerbated the active-passive divide, Moody’s said. Individuals pulled a net $9 billion from taxable bond funds in 2018, compared with inflows of $233 billion in 2017.

Intuitively, active management should never truly disappear, as personal landlines might someday. Is a market that’s entirely passive really a market at all? There will always be investors who think they’re smarter than the crowd. A very select few can make a legitimate claim that they are. And perhaps there’s something comforting about having a human at the helm of a fund, rather than setting it on autopilot.

Even so, active managers have to adapt. They can either join the revolution, as Franklin did by adding a suite of passive ETFs, or further consolidate, as Invesco Ltd. did by acquiring OppenheimerFunds. Neither is guaranteed to work, given how much market share that BlackRock Inc. and Vanguard already command in the low-cost space, to say nothing of Fidelity Investments, which took fees to zero on some of its funds.

The proliferation of passive funds and ETFs, which can accommodate just about any investing strategy, feels like a “technological trend,” in the words of Moody’s, that can’t be stopped. Like it or not, the active-versus-passive shift will prove to be among biggest disruptions to Wall Street in the years ahead.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view