Memory matters. To paraphrase Barbra Streisand’s signature song, what’s too painful to remember, we simply choose to forget—or, at least, recollect very differently from the reality of it at the time. This phenomenon is not just individual but collective as well, not just personal but communal/societal, which is why it’s so important for us to acknowledge it at this moment in history.

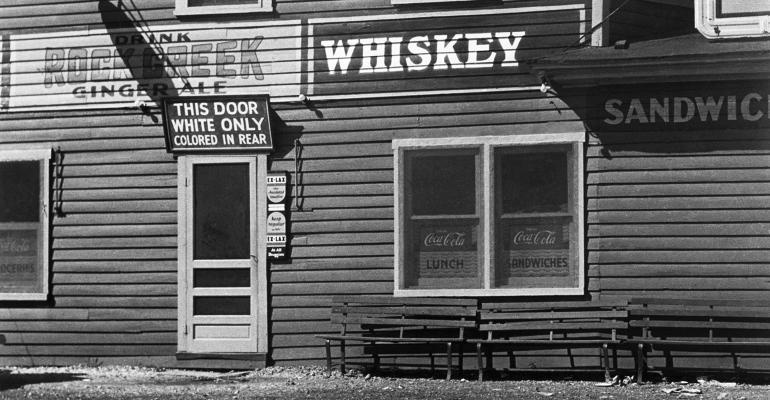

It appears that we’re finally beginning to have the diversity and inclusion conversation in earnest now, after our society has begun to convulse in an unprecedented way in response to what’s been revealed to us about ourselves and how we’ve chosen to live. In this spirit, it behooves us to commit to constructive and candid dialogue and, further, to grounding this in reality, in what was and is, not what we’d wish it to be.

One of the more challenging of these commitments will be acknowledging the impact of our history on our present. This was brought to mind recently when I had the opportunity to speak to a group made up mostly of young people participating in the Financial Planning Association (FPA) Virtual Externship program. While ostensibly we were exploring how financial advisors can serve a more diverse client base, I felt compelled to ground my contribution to our dialogue in the economic history of our country and the resultant, historic income and wealth inequality that’s been its bitter fruit.

So many participants in our webinar contacted me later to express their appreciation for this historical perspective, because they were unaware of it. As I began to reflect on this, it hit me: An important reason that challenging conversations are so difficult for us is that too often we don’t ground ourselves in the full context in which they’re occurring.

To put a finer point on it, that some of the most ambitious and astute early career students of financial planning have no idea about the causes of the glaring, historic and widening economic inequality in our country suggests both that our curricula in this domain are too narrow and that our collective intent to empower people financially could be meaningfully impeded by our lack of (historical/contextual) knowledge and perspective.

Here’s a sampling of what they didn’t know: The externs—some undergraduate students engaged in the study of the discipline of financial planning and others mid-career changers looking to enter the profession—were unaware of the U.S. government’s decisive and extensive engagement in race-based policies that disadvantaged—and in many cases disenfranchised—communities of color in profoundly impactful ways that persist to this day.

If we skip slavery entirely and decide to start later in the 19th century, we can note that former slaves never received their proverbial 40 acres and a mule, but millions of white settlers did receive land grants that became the foundation of their families’ wealth.

If we fast-forward to the 20th century and focus on the post-World War II period in which America ascended to its status as the eminent global superpower (both militaristically and economically), we can study federal housing policy, which was racist to the core. Not only did the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) “redline” areas in which people of color lived, thereby preventing them from having access to the home loans that enabled their white (and largely suburban) neighbors to build unprecedented wealth, but, as Richard Rothstein illustrates so powerfully in his profound and incisive book The Color of Law, it and its predecessors actually installed segregation in residential areas that had never before experienced it.

That’s right, our government proactively disenfranchised communities of color by creating by policy and practice the very ghettos and slums that exist to this day. Or, to state it more bluntly, our government not only encouraged “white flight” to America’s burgeoning suburbs, but it also created structural barriers that would keep all but a few others confined in overcrowded and deteriorating “urban” (read = Black and Brown) neighborhoods that we refer to euphemistically as the “inner city.” (As Rothstein notes, it’s interesting that once these areas become gentrified, largely by affluent whites moving back into them, we no longer refer to them in this way.)

This is one of the most negatively impactful reasons for our racial wealth gap, but we’ve chosen not to remember this but, too often instead, to judge those affected negatively by it.

Why does this matter?

Because if we’re going to deal with diversity and inclusion seriously and holistically, then we must appreciate the actual causes of its absence.

With respect to the racial wealth gap, our purposeful ignorance is quite convenient: Since we claim not to realize the government’s role in creating it, too many of us can decry any role for the government in addressing and alleviating it.

OK, you may say, our government did some pretty messed up things in the past, but much of what’s needed now is determined by private actors, so the former’s influence is limited, right?

In a word, no. In fact, the profoundly negative impacts of the structural racism that continues to undergird our society and its economy have been a reflection of a most pernicious “public-private partnership” for centuries. Our government has not only incented but condoned and expanded race-based exclusion that its private-actor constituents initiated. Therefore, the address of this dysfunction must also include both.

So what can and should we do to address the problem that we’ve created?

Let’s start by using more accurate language and forgo the pervasive presence of euphemism whenever we deal with the very real impacts of the false construct of race in our society. Truth be told, we don’t need to meet the challenge of diversity and inclusion; we need to end the racism, both structural and personal, that’s created it.

Notice that a lot of the terminology that we use to discuss race is purposely designed to soften what is for tens of millions of us a very hard reality. Calling the thing by its name—in this case, racism—is a helpful start in actually addressing it.

Next, we can be guided by the late Stephen Covey’s seven habits in our efforts. In his classic book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, Covey exhorted us to “Be Proactive,” to “Begin With the End in Mind,” to “Put First Things First,” to “Think Win-Win,” to “Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood” (compelling us to listen with the intent to hear, understand and empathize rather than merely to reply), to “Synergize” and then to “Sharpen the Saw.”

In the companion article to follow, I’ll suggest how we can translate this wisdom into practical strategies to pursue in our quest for the successful practice of diversity and inclusion and utilize the financial planning profession as the context for doing so.

For now, let’s agree to embrace reality more openly and honestly in order to change what’s been into what it really should be.

Walter K. Booker is the chief operating officer of MarketCounsel, a business and regulatory compliance consultancy for investment advisors.