Given the numerous recent proposals for the limitation of charitable deductions, now may be a good time to stop and consider just how important state and federal taxation are to clients’ philanthropic decisions.

Every gift is comprised of five elements: (1) Who makes it? (2) Why is it made? (3) What’s given? (4) When is it given? and (5) How is the gift structured?

We spend a lot of time discussing the latter three elements, but it may be wise to step back and explore the “who” and “why” of charitable gifts.

Who Makes Gifts?

It’s estimated that over 80 percent of Americans support one or more charities each year. Some 36.4 million taxpayers reported making charitable gifts totaling $194 billion in 2013, the most recent year for which statistics are available. Itemized charitable gifts have averaged 80 percent of total individual giving for many years.

Recent Internal Revenue Service data reveals that a disproportionate amount of charitable gifts, in terms of number and dollar amount, are made by individuals over the age of 55, with the 21 percent of itemizers over the age of 65 giving fully one third of all gifts that were deducted. These taxpayers also made average gifts nearly twice as large as those made by itemizers overall.

Why Give?

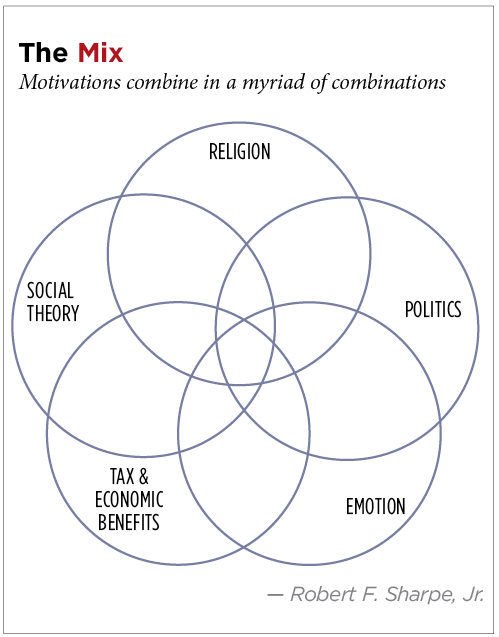

The reasons individuals choose to make charitable gifts are as varied as each unique personality.

Religious beliefs. Perhaps the broadest motivation for giving is rooted in religion. All of the world’s major religions stress the importance of charitable giving. According to Giving USA, religious-based organizations are by far the largest recipients of charitable gifts each year. It’s important for those advising clients regarding their philanthropy to be aware of how their religious beliefs may impact their giving. For example, in some cases, donors may wish to keep their giving anonymous for religious reasons and have advisors act as intermediaries for their gifts, shielding their identities from the recipient organization. Donor-advised funds can serve the same purpose.

Social motivations. The concept of noblesse oblige underlies the giving of some individuals who feel that with their wealth and other privileges becomes a duty to serve society in terms of time and money, regardless of their religious beliefs. They may believe that their leadership status in their communities demands that they shoulder financial and oversight responsibilities for social and other needs. It’s this motivation that leads tens of thousands of individuals nationwide to volunteer their time to serve on governing boards of as many as 1 million non-profit entities registered with the IRS.

Political theory. Another group of individuals give because their political philosophy demands it, regardless of other factors. Examples include those who believe in a very limited role for government that doesn’t include funding social welfare, arts and other activities that they believe are best undertaken by civil society (that is, the aggregate of private entities apart from business and government). They believe that it isn’t the role of government to impose taxes and make decisions regarding a multitude of societal needs, but rather is the province of individuals making voluntary contributions of time and money to meet these needs.

Emotion. A wide range of human emotions are at the core of many charitable giving decisions. Love, anger, compassion, pride and any number of other feelings have long motivated charitable gifts. An individual may make a significant gift in honor of a loved one to memorialize his memory. Or, he may give out of gratitude for a scholarship that was bestowed on him or out of anger focused on a disease that took the life of a loved one and the fear it could afflict him as well.

Tax considerations. Over the past 35 years, I’ve rarely seen the desire to eliminate taxes rise to the level of prime motivator for a charitable gift. And, even when tax considerations were paramount, the individual ultimately decided on the charity that actually received the funds based on one of the above-mentioned motivators. Why is this the case?

First, a rational person doesn’t give away a dollar to save 40 cents. That gift still “costs” the person 60 cents. Second, while there are exceptions, the tax savings will usually be the same regardless of which charity receives the gift. That being said, the final amount of a gift is often heavily influenced by tax considerations. How funds donated to charity are, or aren’t, taxed can influence not only the amount of a gift but also the type of property used to fund it.

The “why” of the gifts is almost always rooted in a combination of non-tax motivators. Advisors often focus on tax and other financial aspects of charitable gifts and understandably so. We can often better serve clients, however, through an understanding of other motivations that are central to the motivation of a gift.

Trusted advisors can often serve to help clients and the charities they wish to benefit balance all of the root motivators in light of very real financial and tax considerations in ways that maximize the tangible and intangible benefits of charitable gifts to all concerned.

This is an adapted version of the author's original article in the March issue of Trusts & Estates.