By Simone Foxman

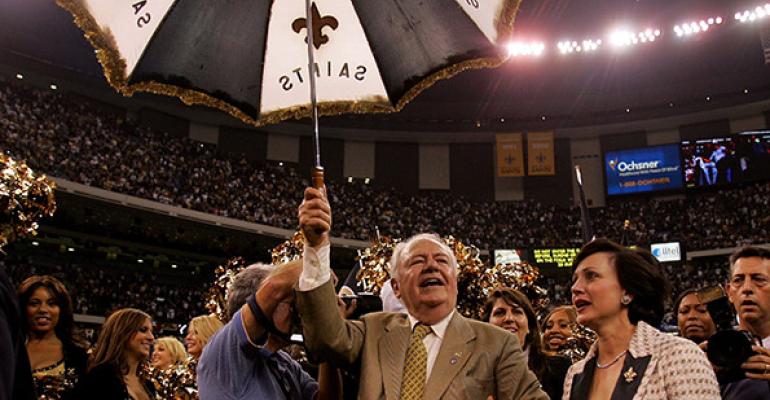

(Bloomberg) -- When Tom Benson died last year at the age of 90, he left behind a sprawling empire that included two professional New Orleans sports teams and a group of car dealerships. Unfortunately for him, he spent some of the last years of his life squabbling with heirs over who would get what.

The legal battle was marked by claims Benson wasn’t mentally competent when he made sweeping changes to his estate plans. His daughter and two grandchildren alleged he was acting at the direction of his third wife, Gayle Benson, 72, whom he married in 2004. Tom Benson rejected the claims, and a Louisiana court agreed. When all was settled, his wife ended up with the New Orleans Saints and the New Orleans Pelicans and his daughter and two grandchildren got most of his other holdings. But it took a lot of time, a lot of lawyers—and presumably a lot of money.

This kind of drawn-out fight for control is a risk faced by a growing number of longer-living American billionaires. At least 15 of them died last year, leaving behind assets collectively worth about $60 billion, including all the complex trappings that come with immense wealth: wide-ranging business interests, properties, sports teams, yachts, planes—you name it.

The number of U.S. billionaires has grown swiftly of late. There were an estimated 747 of them in North America in 2017, up from 490 in 2010, according to a study. At the same time, long-term economic data suggest the 10-figure crowd and those just behind them control ever-larger pieces of the economic pie. The wealthiest 1 percent control 37.2 percent of the country’s personal wealth, while the bottom 50 percent control nothing.

And the rich are living longer than ever, adding years of asset accumulation at a time when income inequality has become a political flashpoint. While cuts to estate and gift taxes are partly to blame for the concentration of wealth, another cause is a growing advisory industry aimed at making sure all that money goes exactly where the super rich want it to go.

A New Orleans native, Tom Benson got his start selling cars, first in Louisiana and then Texas. In 1985 he was part of a group that bought the Saints franchise, now worth almost $2 billion, for $70.2 million. In 2012, he bought the Pelicans for $338 million. That franchise is now worth about $1 billion.

The fight over his estate began playing out in 2014, after the billionaire, then 87, shifted future control of some assets from his daughter Renee and her children to his wife, Gayle Benson. The grandchildren, Rita and Ryan LeBlanc, had been involved in running parts of the family businesses. The dispute culminated in a mental competency hearing, where a New Orleans judge held that, despite “memory lapses,” Benson was able to manage his own affairs.

Another prominent case involved a multibillionaire still among the living. Disputes over the competency of 95-year-old Sumner Redstone led to four years of litigation over his assets and business holdings. In January, Redstone settled a long-running legal fight with a former lover and confidante. The deal resolved all pending lawsuits between him and Manuela Herzer, who after a falling-out had sought to be reinstated as Redstone’s health-care agent. This triggered a cascade of litigation around his family’s control of the media empire, Redstone’s pay and his daughter Shari’s influence over his $3 billion fortune.

“Stepping into the shadows is something that older people don’t want to do.”

These days, the fortune of modern-day billionaires is “so large that it’s anticipated to last for not just children or grandchildren or even great-grandchildren, but great-great-grandchildren who these patriarchs will never know,” said Elizabeth Glasgow, a partner at Venable LLP who specializes in succession and wealth planning. And with that expectation comes the increased threat of litigation.

So it’s not surprising that 45 percent of wealth management firms now offer estate and succession planning as primary services, up from 37 percent just a year ago, according to Cerulli Associates. The data provider estimated that demand for these capabilities will continue to snowball: Over the next 25 years, $68 trillion of wealth will be transferred in the U.S. alone.

Most major banks now advertise “family office” and planning services for clients with more than $25 million in investable assets. Some offer perks for the super-privileged: Wells Fargo & Co.’s family office group has a historian to document family legacies, while Citigroup Inc. and Deutsche Bank AG boast summits that teach heirs how to invest in Silicon Valley.

Longevity can be critical to the growth and long-term success of such family business interests, said Jonathan Flack, who leads PricewaterhouseCoopers’s U.S. Family Business unit. In earlier eras, longer lifespans were driven by declining child mortality. In the past 50 years, the driver has been older people living longer. Men in the top one-fifth of America by income born in 1960 can on average expect to reach almost 89, seven years more than their equally wealthy brethren born in 1930. (Life expectancy for men in the bottom wealth quintile remained roughly stable at 76.)

John Davis, founder of Cambridge Family Enterprise Group, said advising clients on how to successfully hand off power increasingly requires finding them a life beyond their business interests, given how long the rich are living. Davis, who teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, said he started paying more attention to the challenges raised by longevity about 15 years ago, when he realized several clients had three generations of adults involved in the family business. “The oldest generation was still around,” he said, “and not just still around, but still active and still wanting a role.” That could be a recipe for disaster.

“Stepping into the shadows is something that older people don’t want to do. It’s kind of scary,” said Davis, who has made a career of advising ultra-rich families on how to transfer wealth. Data reflect this hesitancy: Just 18 percent of family businesses in the U.S. said they have a robust succession plan, according to a 2019 survey from PwC.

Flack tells clients that early planning can allow for a more efficient transfer: for example, asset owners who assign shares of a company to a trust earlier, at a lesser valuation, can avoid some taxes if the business appreciates. But Glasgow warns that such concerns must be balanced with the possibility that children or trustees might “jump the gun” to have them declared mentally incapacitated.

“The state of diminished capacity isn’t going to be a bright line,” she explained, given the vagaries of such diseases as dementia or Alzheimer’s.

In the past, an aging tycoon may have relied on a trustee or family friend to make the call. Nowadays, the rich are planning for the possibility of a slow decline, making use of vehicles to transfer wealth or fund philanthropy while keeping control longer. And for protection, Glasgow said, the rich are introducing clauses in wills that require heirs to produce two, or even three, doctors who agree they are unfit to administer their own estate. One client stipulated that only a court could determine whether he was mentally incapacitated, she said.

“If you start early enough and do it long enough, you can move a lot of money without estate tax.”

Then there are the taxes—or, more specifically, minimizing them. Take the dynasty trust, an increasingly popular structure designed to move large amounts of money into a long-term vehicle that can pay future generations while limiting estate and generation-skipping taxes. Such vehicles allow the wealthy to pass chunks of their businesses to descendants tax-free, provided they fall under gift-tax exemptions—currently $22 million for a couple.

Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts, or GRATs, can be particularly effective for passing on wealth when employed over decades, said Steve Antion, an attorney for Winston & Strawn LLP in Los Angeles. He advises clients to stash some of their more volatile existing investments in these structures for short periods, a minimum of 2 years.

At the end of the term, the client gets her money back plus a statutory interest rate—3 percent annually as of April. An heir who is the beneficiary of such a trust gets everything else and doesn’t have to pay taxes on it. A $10 million initial investment that appreciates 25 percent over three years would return $11.02 million in principal and interest to its creator (assuming a stable interest rate). The rest of its gains, some $1.48 million, would be transferred to heirs tax-free.

Once each GRAT expires, Antion advises clients to roll the investment into a new one, and repeat the process. The strategy is “amazingly effective and completely legal,” he said. “If you start early enough and do it long enough, you can move a lot of money without estate tax.”

But even in the best of circumstances, balancing tax benefits with maintaining control of your assets is tricky. Those who pass on their wealth or business too early can find themselves on the sidelines sooner than they’d wanted. Still, doing so early and quietly might just avoid the kind of mess Tom Benson found himself in. Careful planning won’t cure all family drama, but it just might keep it out of the headlines.

To contact the author of this story: Simone Foxman in New York at [email protected]