The DOL push created substantial challenges in communicating the new rules.

Worse still, the regulatory shift from the ERISA rules born in 1974 now extend a fiduciary duty to advisors relative to IRAs that can lead to unbridled confusion and abuse.

Consider the two hats worn by a financial advisor. An advisor does not have a fiduciary duty when he or she communicates with or engages a client relative to assets outside of retirement plans and IRAs. Envision a conversation between an advisor and a couple planning for retirement. The conversation shifts from a discussion about the couple’s holdings in an IRA to their individual investment in a mutual fund account.

Does the advisor temporarily halt the conversation and advise that he or she is “no longer acting as their fiduciary”? Does the advisor say, “I can now give you advice that may not be in your best interest, but trust me, I will always act in your best interest”? Does the advisor even say anything at all?

As consumers realize there is an obligatory fiduciary status cast on their advisors, they will naturally expect that all advice will be governed under the same standard. And, predictably, many consumers will discover that their advisors were wrong and, feeling betrayed, will litigate, causing even more chaos in already complex and confusing terrain. It’s likely that such uncertainty and litigation relative to the new DOL position will build until the SEC requires fiduciary duty for all investment advice. And, ultimately, every transaction proffered by financial advisors will be governed under the same standard.

But what then? Under what standard will wealth advisors be judged if they sell interests in their broker/dealer’s proprietary funds but should have known that a no-load product exists that acquires the same equities at a lower cost?

Meaningful change is not limited to traditional investments and retirement plans. Disclosure as it relates to life insurance has also been ratcheted up. The most visible changes relate to the way life insurance is illustrated to consumers. Actuarial Guideline 49, initially intended to address aggressively high rate-of-return assumptions in indexed universal life insurance (IUL) illustrations, now encompasses rules related to the illustration of policy loans.

So, what happens when the proverbial rubber meets the road? For example, a recent life insurance illustration contained 78 pages of content, including scores of financial projections. This complexity, added to the disclosure of what is being touted as consumer-friendly illustration methodology, only serves to convince consumers that the ice is safe to skate on. But when nearly every lever in an IUL policy can be pulled by the insurer to raise costs (essentially eliminating all but the “guaranteed” values as reliable), by the time policy owners realize that the ice is too thin to support them, they may already be at the bottom of the lake. After all, a guaranteed return only guarantees revenues. The net return needs to take into account charges and fees that can arbitrarily escalate.

One would think that with all of this disclosure there might be some dampening in the sales of IUL policies, or a substantial shift toward whole-life products. But that’s not the case.

If AG 49 affords no meaningful advantage to buyers of life insurance, then what was the real reason for the change? Could it be that financial institutions bolstered their defense against consumer-based litigation under the guise of transparency? Are the regulations simply a movement toward populism, as some have argued? Does anyone even know what the true intent was behind the changes?

Perhaps these questions reflect too sinister a view of the financial-services industry and its efforts to generate profit. Given that tens of millions of dollars have been spent on introducing the new DOL fiduciary rules and AG 49, one might expect newly savvy investors to be scoring higher net returns, deftly avoiding investment dips or, at a minimum, sidestepping risk. But there is no meaningful evidence of such advancements. There has been no paradigm shift, no earth-shaking realignment in the types of insurance policies sold, no notable increase (or decrease) in retirement-plan contributions, and the above-the-fold headlines touting, “Consumers are making better choices,” have yet to be published.

Where are the clarion calls from advocacy groups or their bulk email campaigns alerting consumers that today’s regulatory victories herald a time to revisit financial matters? Basically, anything and everything can be found on the Internet, but search the web looking for specific evidence of consumer victory in the above matters and what you’ll mostly hear are crickets.

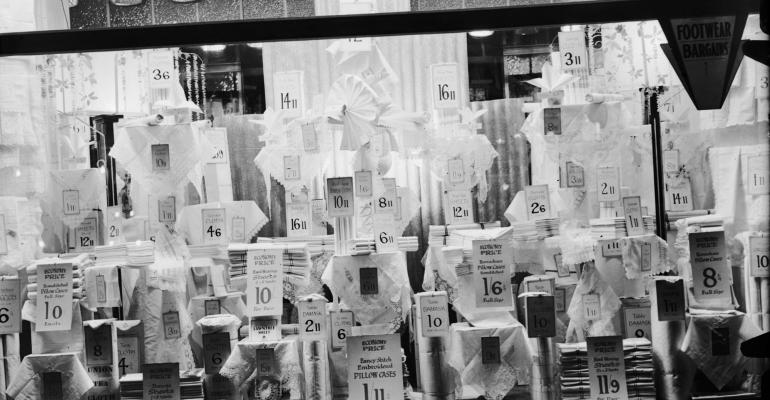

Both the Obama and Trump administrations, along with members of Congress, promised to “shake up Wall Street” and/or “drain the swamp.” In delivering their vows, our regulatory bodies have, allegedly, scrubbed the windows of transparency so that they appear clear. But in a world in which consumers of financial goods have become colorblind to varying shades of truth, little has changed beyond Wall Street's bulletproofing its own tinted glass.

Jerry Hesch is an attorney, professor, author and speaker on estate-planning and taxation law. He is the director of the Notre Dame Tax & Estate Planning Institute. Brad Barros is the senior risk analyst consultant for the law firm Rodnunsky & Associates. He is also the CEO of My National Family Office, Inc., and the creator of Iron Dome Insurance.