Some advisors say that, given enough time, a dollar deducted is like a dollar saved. But so-called truisms borne of the wealth management industry are often like magic tricks: the audience only sees what the magician fashions. So when the founder of a large surgical center retained us to examine a proposed micro-captive insurance company (MC) and compare it with a pension plan, we were more than happy to examine the magician’s box of tricks in order to divulge his secrets.

Meet Dr. Smith (not our client’s real name). He is a veritable superstar. At only 38 years old he earns about $4 million a year from his medical practice and surgical center. While his medical practice had a large number of self-insured risks, the doctor appeared motivated by what he believed would be the long-term tax savings promised by the captive manager. When all regulatory and IRS standards are met, premiums paid into a captive may be deductible. Underwriting profits inside an MC are tax deferred, but all realized investment gains are taxable. If the MC has reserves that remain after paying claims to the doctor’s business (and claims paid to third parties who would participate with the MC in a compliant risk pool), the captive may be liquidated on a capital-gains basis, where remaining untaxed underwriting profits and previously taxed investment gains will be taxed again.

Dr. Smith’s outlook is one that we have seen many times. A client may have the requisite business purpose to justify an MC, but the true primary interest in is tax savings. That in itself is not enough reason to justify a captive insurance company.

We support the use of captive solutions in certain instances to protect against a variety of risks and to lower the cost of insurance. For some clients, a lengthy period of time may occur before one’s captive insurance company pays claims. In these instances, the deferral can foster meaningful cost savings. We cautioned the doctor that his primary objective for a captive must be for proper business purposes, including cost savings and increased protection, and not for tax-planning purposes. We also detailed the cost of administration, risk-pool participation fees, and third-party claims against his captive. The doctor hoped that the potential tax deductions would make the captive the best long-term solution for his company’s profits. But when Dr. Smith more fully understood the long-term cost of the MC, he changed his tune.

Accordingly, we suggested the doctor examine other options that were potentially more in tune with his needs, and whose compliance did not require risk management as the primary driver. The comparison included a pension plan, after-tax savings and a no-load private-placement life insurance policy (PPLI). Starting with the pension plan, we interviewed several retirement-plan administrators and determined which type of plan would provide the largest pension allocation to Dr. Smith. In the best-case scenario, the plan would be able to allocate approximately 90 percent of the pension benefit to Dr. Smith and only 10 percent to his employees (who already participated in a 401[k] plan).

We explained that the money in his pension plan would be exposed to future tax increases at retirement (a concern he shared). We also explained the regulatory scheme penalizing pension participants taking distributions before age 59½, and, similarly, the forced taxable minimum distributions at 70 to avoid penalties.

We then discussed the other alternatives. The first was nothing more fancy than investing after-tax dollars with his trusted investment advisor. While the realized gains would be taxable, Dr. Smith would have full control over the investments and could have his wealth managed in a tax-sensitive manner. He could select both bankable and non-bankable assets, such as real estate and private equity. Dr. Smith liked the fact that he was not directing his money into an area heavily regulated by the federal government and insurance regulators.

The final alternative was for Dr. Smith to acquire a non-MEC PPLI. After interviewing several carriers, we suggested one that was fee based, with a low fixed fee and commission free. The insurer agreed to allow the doctor to keep his existing trusted investment advisor and trust company for money management and custody. As with the after-tax savings option, the insurer would allow investment in both bankable and non-bankable assets. Also similarly, the premiums would be paid with after-tax dollars. Unlike the savings plan, gains in the insurance policy grow tax deferred and may be accessed tax free, either by withdrawal up to cost basis or by a policy loan. To further lower costs, the insurance carrier allowed the doctor to finance the insurance policy’s mortality costs with no out-of-pocket costs.

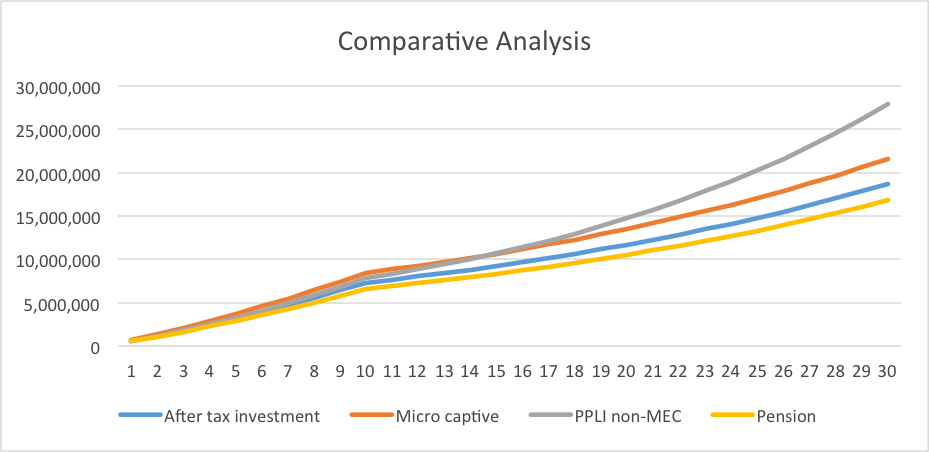

The economic results of our analysis were eye-opening to Dr. Smith and are provided below. As a benchmark, we assumed level pretax funding of $1,000,000 for 10 years. While the pension would not allow for contributions of this magnitude, we chose the number because the captive manager had underwritten the medical practice and determined it to be the maximum premium.

We assumed a taxable distribution from the captive in the 11th year, and projected growth in all options to age 65, when Dr. Smith intended to retire from his business interests. The pension analysis presumed the after-tax value in all years (excluding the application of any pre- or post-retirement distribution penalties). We used a 6 percent gross rate of return in our original modeling. Dr. Smith asked us to include the trailing 10-year S&P 500 Index, which we have included in this article. We used $560,000 as the net funding (the doctor had a combined 44 percent federal and state income tax rate) for the after-tax options. We assumed that Dr. Smith’s current money managers could manage the assets in each option. The results below are net of all fees and taxes. The detailed analysis is available upon request.

Hypothetical Comparative Analysis

| Year 10 | Year 20 | Year 30 | |

| After Tax Self Insurance: | $7.3M | $11.7M | $18.7M |

| 831(b) Micro captive: | $8.4M | $10.1M | $16.2M |

| Private Placement Life Insurance: | $8.8M | $14.7M | $27.9M |

| Pension with 10% employee cost: | $6.5M | $10.5M | $16.8M |

The tax-deductible captive and pension options remained competitive for a modest period of time. Yet in the long run, the law of diminishing returns due to an excess of expense dissolved the initial benefit derived from the tax deduction. The after-tax savings provided more net retirement values than the captive and the pension, without any of the ERISA plan’s restrictions or exposure to third-party claims. It should be noted that the captive provided more (early) protection from a business loss than all other options. However, Dr. Smith’s most important objective was wealth at retirement. It’s true that Dr. Smith would not likely liquidate his pension all at once; so, a net-income analysis was also provided, illustrating a similarly corrosive effect from taxation on the plan’s distributions. The pension also generated a valuable employee benefit, which was not available with the other plans. That said, Dr. Smith could always allocate some of the excess funds from the after-tax options as a bonus to his employees. As to the PPLI, it required the use of an insurance dedicated fund or manager. That said, it far surpassed the other options.

With such a large economic disparity between myth and reality, Dr. Smith was left wondering how he had become so enthralled with the captive and pension. After all, there is a sea of articles written espousing the virtues of tax-deductible planning.

As with a deck of cards in the hands of a skilled magician, it’s often what the audience doesn’t see that’s most important. In Dr. Smith’s case, he didn’t understand the corrosive cost of the up-front and ongoing captive management fees, as well as the long-term impact of third-party claims and double taxation on realized gains. He also didn’t appreciate the impact of employee costs and retirement tax on his pension. And while he valued the pension’s tax-deferred growth, he hadn’t considered the risk he was taking by potential exposure to even higher taxes in the future.

Critically, we could argue in favor of or against each option subject to the doctor’s personal planning initiatives. But what was most important was providing transparency on a fiduciary basis, so that Dr. Smith could make the right choice for himself.

Jerry Hesch is an attorney, professor, author and speaker on estate-planning and taxation law. He is the director of the Notre Dame Tax & Estate Planning Institute. Brad Barros is the senior risk analyst consultant for the law firm Rodnunsky & Associates. He is also the CEO of My National Family Office, Inc., and the creator of Iron Dome Insurance.