(Bloomberg) --

If Steve Cohen’s bid for the New York Mets succeeds, he’ll find himself in familiar company.

Hedge fund managers and private equity titans are an increasingly common sight in the owners’ boxes of Major League Baseball teams, including former trader John Henry at Boston’s Fenway Park, Guggenheim Partners’ Mark Walter at Dodger Stadium and Crescent Capital’s Mark Attanasio at Miller Park in Milwaukee.

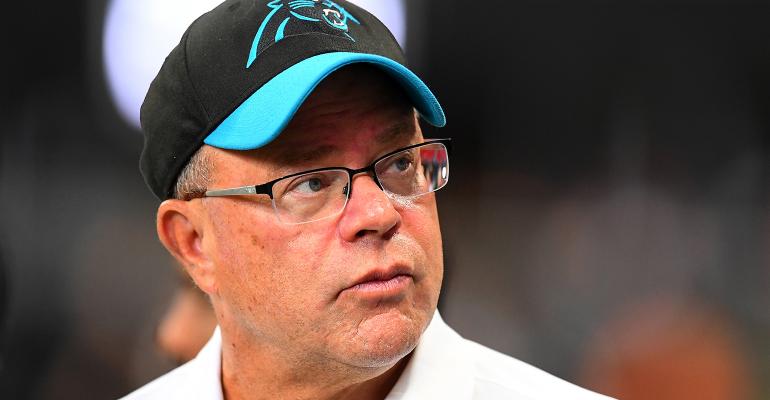

And it’s not just America’s Pastime. Pro football franchises, basketball teams and soccer clubs also are attracting the financial elite. Last year, David Tepper bought the NFL’s Carolina Panthers. The principal owner of the NBA’s Golden State Warriors is former venture capitalist Joe Lacob, while Platinum Equity founder Tom Gores owns the Detroit Pistons.

“One of the great sources of the kind of liquid capital you need to buy a sports team are people in the finance industry,” said Marc Ganis, president of consulting firm Sportscorp Ltd. “Tepper could simply write the check for the Carolina Panthers. Literally write the check. And Steve Cohen is the same.”

The lure is no longer just the prospect of owning a trophy asset or hanging out with famous athletes, although that still resonates. These days there’s also a cold-eyed appraisal of teams as an increasingly astute financial bet, backed by a mix of real estate, media and technology.

“Steve is a consummate businessperson who will bring insights to the way the sport is evolving to the team management,” Leo Hindery, founder and former chief executive officer of the Yankees’ broadcast network, said of the hedge fund titan in an interview this week.

Cohen’s proposed bid underlines the astronomical cost of teams in major markets these days. Fred Wilpon, the Met’s principal owner, made his money in real estate. He assumed control of the franchise in 2002 at a valuation of just $391 million.

Cohen — one of the most successful hedge fund managers in history with a net worth in excess of $9 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index — is negotiating to buy an 80% stake that values the team at a league-record $2.6 billion. That’s a 550% increase in less than two decades.

Jerry Richardson paid about $200 million in 1993 for the rights to start the Panthers. Tepper, founder of Appaloosa Management, paid $2.3 billion for the franchise last year. The Milwaukee Bucks, worth $18 million in 1985, fetched $550 million when the NBA team was sold to Marc Lasry and Wes Edens in 2014.

It’s a similar story with soccer. The enterprise value of the 32 most prominent European clubs increased to $41 billion at the start of 2019, up 35% from three years earlier, according to a KPMG report.

Finance is the source of 106 fortunes on the Bloomberg index, a ranking of the world’s 500 richest people. That’s about double the number of those who made their money from technology. Outside of the top 500 are scores more with the means to pay the price tags the biggest sports teams now command.

When the Panthers came up for sale, three billionaires with financial backgrounds dominated the bidding war, with Tepper ultimately beating out Ben Navarro, founder of Sherman Financial Group LLC, and investor Alan Kestenbaum.

“I don’t want to own a trophy asset,” Kestenbaum said during the bidding. “An investment of this size has to continue to grow in value.”

That remains a distinct possibility, even at today’s elevated prices. Long-suffering sports fans — buffeted by ownership changes and rising ticket prices — tend to remain loyal to their teams, while the seemingly evergreen allure of live sports has kept the value of television rights packages buoyant.

The appeal is such that it’s not just individuals investing. Last month, private equity firm Silver Lake Management bought a piece of City Football Group Ltd., owner of the Manchester City soccer team, valuing the parent at $5 billion. CVC Capital Partners bought a minority stake in England’s top rugby league last year having previously owned race series Formula One for a decade before selling it to John Malone’s Liberty Media Corp. for $4.4 billion.

Owning such illiquid assets requires a high tolerance for risk and a healthy balance sheet. But that’s second nature to many of the mega-wealthy financiers now filling board rooms. For hedge fund executives used to the volatility of capital markets, the limited supply of these teams is appealing. Even when an owner has sold under duress — such as former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling or the Panthers’ Richardson — the price they received set records.

Plenty of financiers have doubled down on these types of investments. In addition to the Red Sox, Henry owns England’s Liverpool Football Club and half of Nascar’s Roush Fenway Racing team. Major League Soccer’s board of governors agreed Thursday to move forward on the final steps toward granting the latest expansion team to Charlotte, North Carolina. The bid was led by Tepper.

His growing taste for sports teams is no surprise to those in the industry.

“There’s a competitiveness in the finance sector at the highest levels, which translates very well into the sports industry,” said Ganis, the consultant. “It’s wins, it’s losses, it’s zero sum games. It’s kill or be killed. That has a lot of similarity to the sports industry where at the end of the season there are winners and losers.”

--With assistance from Tom Maloney, Scott Soshnick and Eben Novy-Williams.

To contact the author of this story:

Tom Metcalf in London at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Steven Crabill at [email protected]