The bond market is changing.

Naturally, it’s always moving pricewise, while broad changes such as asset-class weightings tend to come at a glacial pace, imperceptibly as far as a trading market or even longer-term strategy is concerned. Consider month-end index changes: we pay attention for a minute, adjust, move on.

But get ready for some serious shifts, noticeably and soon. I’m referring to the broad market weightings as tracked by SIFMA and the impact of rising Treasury budget deficits even before the latest tax plan was imposed on the budget. Treasurys as an asset class are increasing, and it’s not a far leap to speculate that the duration of the bond market will increase along with them.

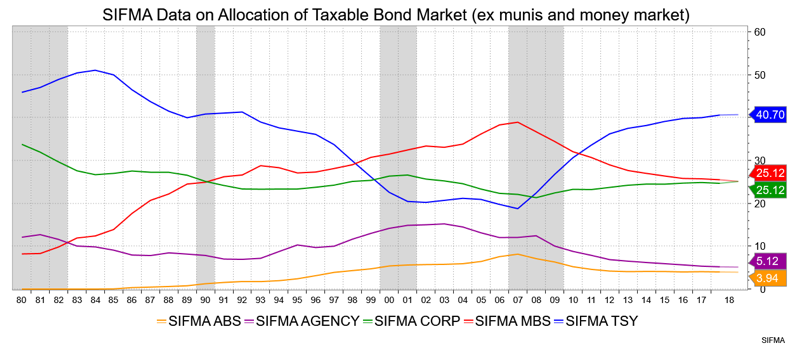

To wit, Treasurys as a percent of the taxable bond market are just over 40 percent; as recently as 2007, they were half that amount. Their relative increase is a function of the deficit growth coming out of the last recession and a comparable diminishment in other issuances, namely mortgage-backed securities, agencies and asset-backed securities. That trio is now about 25 percent, 5 percent and 4 percent of the market, respectively; back in 2007, those accounted for 39 percent, 12 percent and 8 percent, again, respectively.

This chart is a snapshot of where we are and where we’ve been.

It’s interesting to note the gain in the Treasury weighting, even during the various phases of quantitative easing, as what the Fed bought was extracted from the float. Now, as the reverse takes place (call it quantitative tightening), what the Fed doesn’t buy goes into the float or increases the paper the market has to buy.

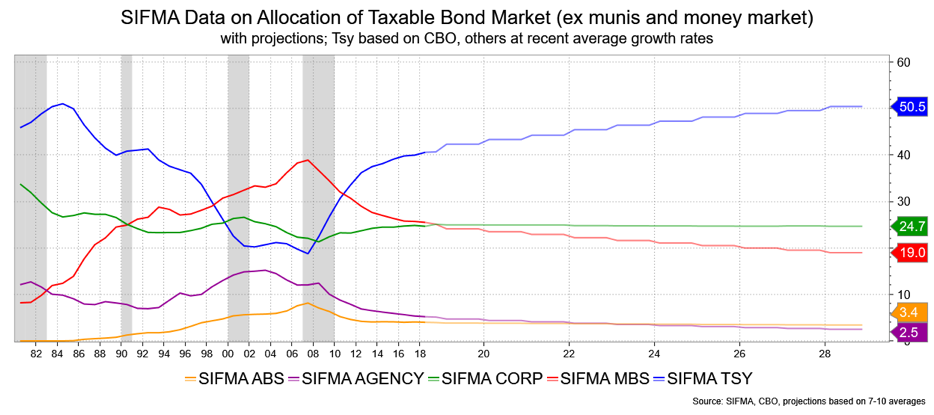

The budget is the bigger deal—vastly so. To project forward, I took the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for the budget (Debt Held by the Public) and simply applied that as a forecast. Then I took the average gains in the other categories over the last few years and applied that rate to those categories going forward. None had negative changes. We’ll call those assumptions.

This chart shows how things will change. Treasurys will go from about a 40 percent weighting to 50.5 percent in 10-years’ time. Note that this doesn’t allow for an increase in our debt based on, say, a recession or revenue growth slowing relative to the Congressional Budget Office’s forecasts. Conversely, it doesn’t allow for any optimism of growth coming in faster than expected with revenues gaining accordingly.

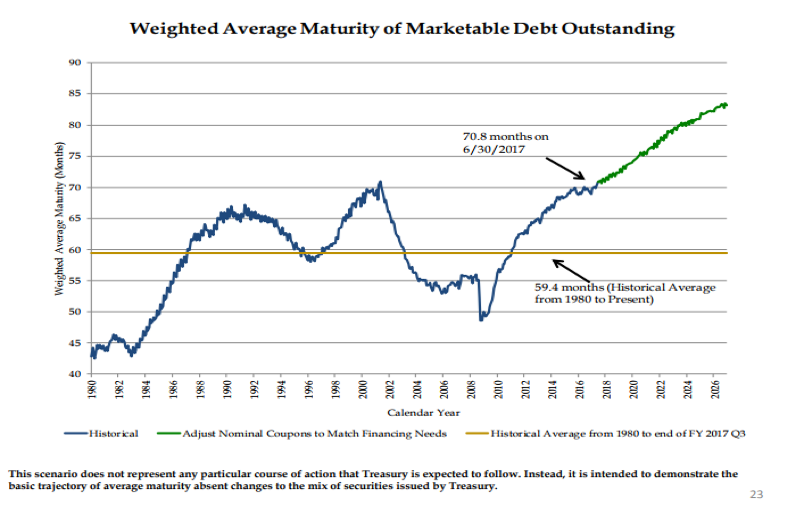

Last year, in a Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee presentation, the group offered a projection of the weighted average maturity of marketable debt outstanding. What they saw was a rise from 70.8 months a year ago to about 84 months in 10 years. I think that’s about right, too. Between relatively low historical rates and, presumably, a flatter curve for a while, it’s prudent for Treasury to issue more long-term debt (10-year Treasurys and 30-year Treasurys) and debt of a longer maturity (say, 40-year Treasurys or 50-year Treasurys). And, anyway, the government seems to have little inhibition in kicking the proverbial deficit can down the road.

Are you with me so far? If you are, you have a sense of how much Treasurys will be of the taxable bond market and that the average maturity of Treasurys is likely to increase. What this means for a broad index, like the Bloomberg Aggregate is that investors, especially the growing category of passive bond investors, will have to buy more and more Treasurys to keep pace with the index and, likely, those Treasurys will have a longer and longer average maturities, thus providing a forced buying class, which should dampen rate gains to longer-term Treasurys, in other words, a backstop.

A sideshow to the big show is how this has behaved in the recent past. So, Treasurys rose to 40 percent of the market in the last 10 years due to both increased issuance and, more importantly, diminished issuances in MBS, Agencies and ABS. I don’t see those coming back, nor do I see new asset classes coming to the fore. In fact, I imagine we could see a slowing in the pace of some issuances (I’m thinking corporates). With the Fed’s balance sheet reduction, the risk is that more of that influence boosts the allocation more than projected and sooner than forecast.

Consider the last 10 years yet again. The doubling in the Treasury component likely boosted the “need” for Treasurys by any given index-benchmarked investor. But, with the Fed’s buying, taking bonds away and out of an index, that “need” was somewhat diluted. No more. Between the Fed and the deficit, Treasurys are set to rise to their prior heights, ironically back to the 50 percent market they were in at the start of their great bull market. That point is more a coincidence than expectation for the start of another grand bull market in 2028.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.