Once a quarter, you come across a gem in the form of the Quarterly Review and Outlook from Hoisington Investment Management, written by Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington.

In the Quarterly, HIMCO gives a perspective on growth utilizing tried and true, but I think largely overlooked today, views from what I consider a monetarist perspective. It’s an instructive and valuable insight.

There’s an unveiled warning in all this, which anticipates moderating growth. The Quarterly starts with a discussion of Milton Friedman’s modeled version of the Irvin Fisher equation, which concludes that monetary decelerations can lead to higher rates initially, but ultimately lower interest rates and that the reverse is true. Think simply of Fed hikes and yield curve flattening. The logic to that is what are deemed liquidity, income and price effects. To wit, when the Fed reduces or slows the various money aggregates, you have the liquidity effect lifting rates. That’s where we are now. Tighter policy provides an offsetting income effect, slowing the pace of rising rates. The liquidity effect comes first. Now consider all that with what follows.

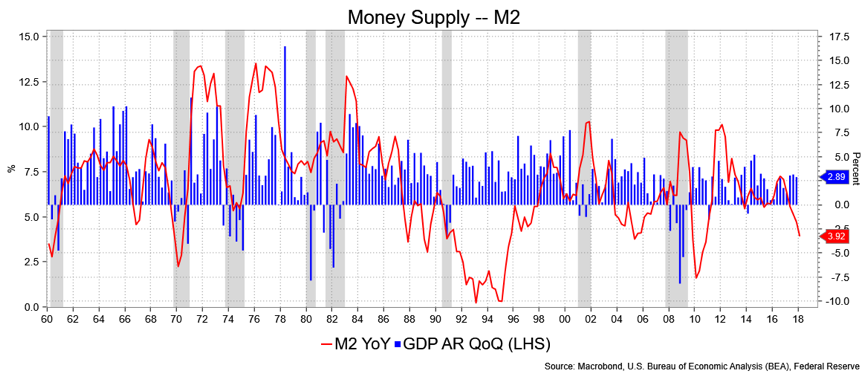

They point out that since the start of the last century, 17 out of 21 recessions were preceded by a drop in money supply as measured by M2. Guess what M2 is doing today? It’s slowing rapidly. At 3.9 percent year-over-year, M2 is at its slowest growth rate since early 2011 and near the lows of the last growth cycle. That there is a strong correlation between M2 growth and GDP is, in the words of Messrs. Hoisington and Hunt, “remarkable given the complexity of the economy and shifting initial conditions.” Still, the correlation is there. M2 peaks typically about two years before a recession, though that is naturally variable.

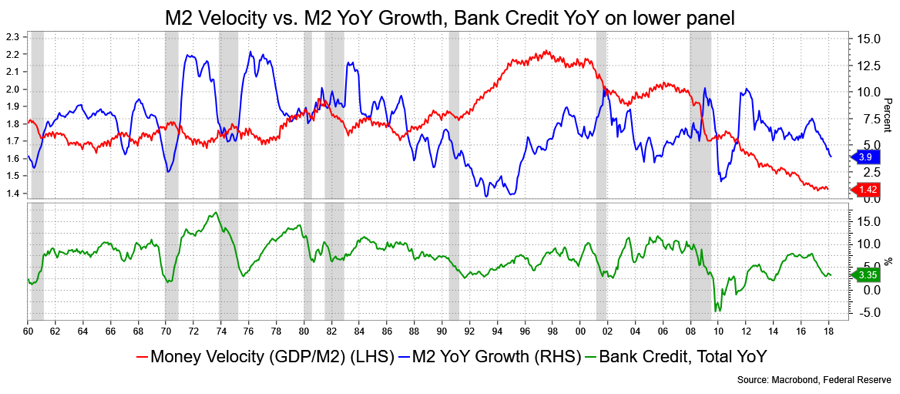

They astutely chose to look at the four episodes when M2 did not peak before a recession to see what was different. One was in advance of the 1923 recession. Money velocity was falling (as it’s doing now) and the yield curve was flattening (as is happening today). Another moment was before the 1958 recession. Then, the rate of growth in the monetary base did slow sharply, bank credit came off (which it’s doing now) and the yield curve inverted.

They made a good point about the back-to-back episodes of 1980 and 1982, as being considered by many really one recession. M2 did slow prior to that joined period, as did other aspects alluded to above, so they see no contradiction if you look at that period as just one protracted recession.

Then there’s 2008, when M2 did not slow down, but other monetary variables were indeed restrictive; the curve inverted in 2006, when the Funds rate peaked at 5.25 percent, and so on.

In short, while M2 behavior may have not conformed to the model, many if not most other features did. Now, M2 is behaving in line with the recessionary caution. For example, in Q1, M2 growth grew at a 2 percent annualized rate and a 3.9 percent YoY. Contrast that with the 6.6 percent long-term mean.

And while I’m at it, what’s happening with Velocity? Money Velocity is 1.42 (GDP/M2), the lowest it’s been in decades—well over 50 years, based on the official data. Hoisington makes an interesting, although certainly not widely popular, point about the impact of the Fed’s tightening. To wit, between the end of 2015 and now, the monetary base has fallen over 6 percent and excess reserves are off by 16 percent, which the authors attribute largely to the Fed’s hikes and reduction in the balance sheet (“quantitative tightening” in their words). Further, they note the slowing pace of commercial bank credit over the recent time frame: “Together, reductions in the base and the money multiplier have caused the rate of growth in M2 and commercial bank credit (the sum of loans and investments) to slow noticeably.”

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.