By Chris Hughes and Marcus Ashworth

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --Bond buyers are giving the Michelin Man a free lunch. In fact, they're giving a number of European companies free lunches. They'll even pay for the privilege.

Madness? No. It's the convertible bond market.

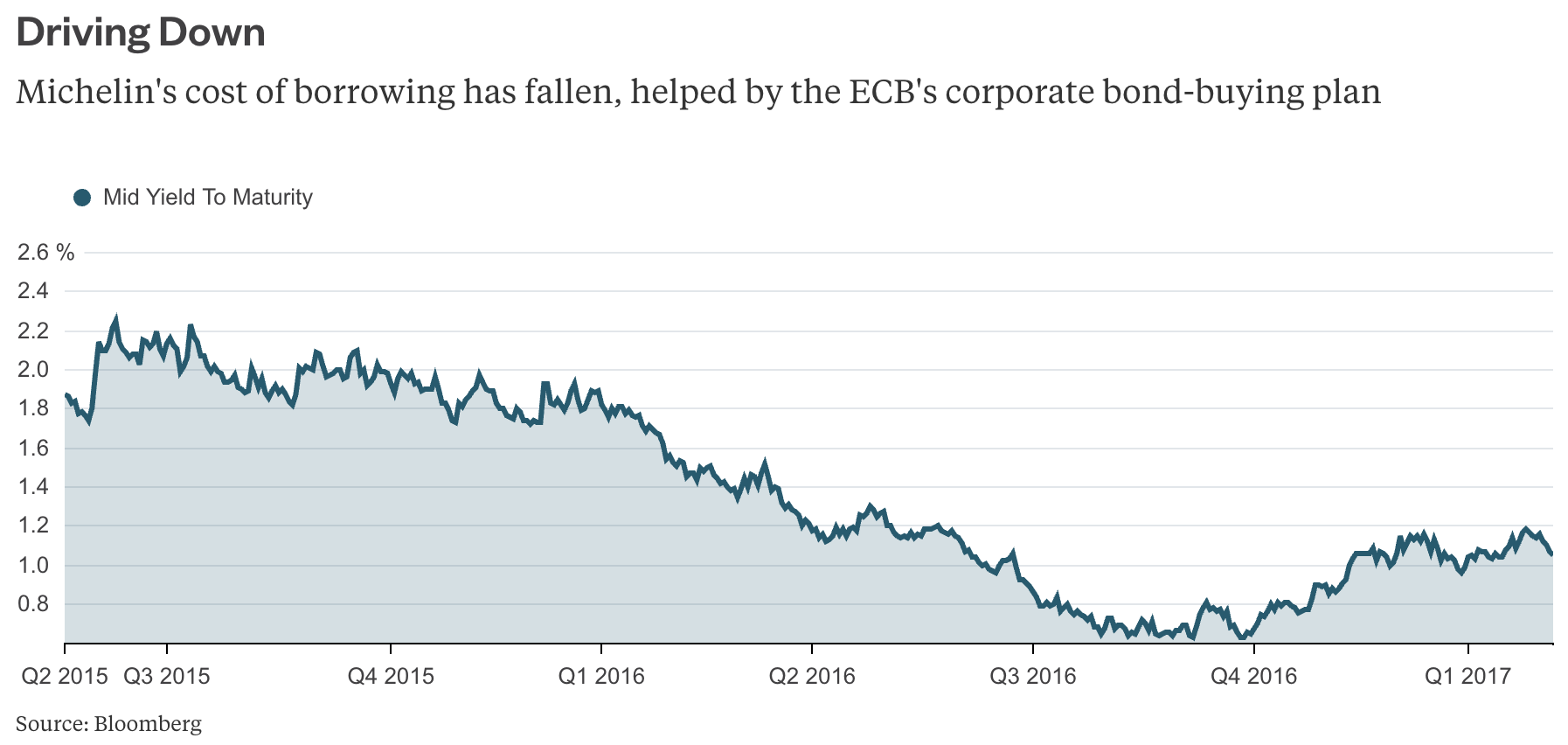

Michelin & Cie., the French tiremaker, and German healthcare provider Fresenius SE have kicked off the year by borrowing at even lower rates than their already super-low bond yields. That's because funds that buy nothing but convertibles and hold them have more money than they know what to do with.

While ordinary bonds are always redeemed in cash, convertibles are redeemed in shares if the issuer’s share price rises above a certain level over a prescribed period. Hence the name: the bonds convert into stock.

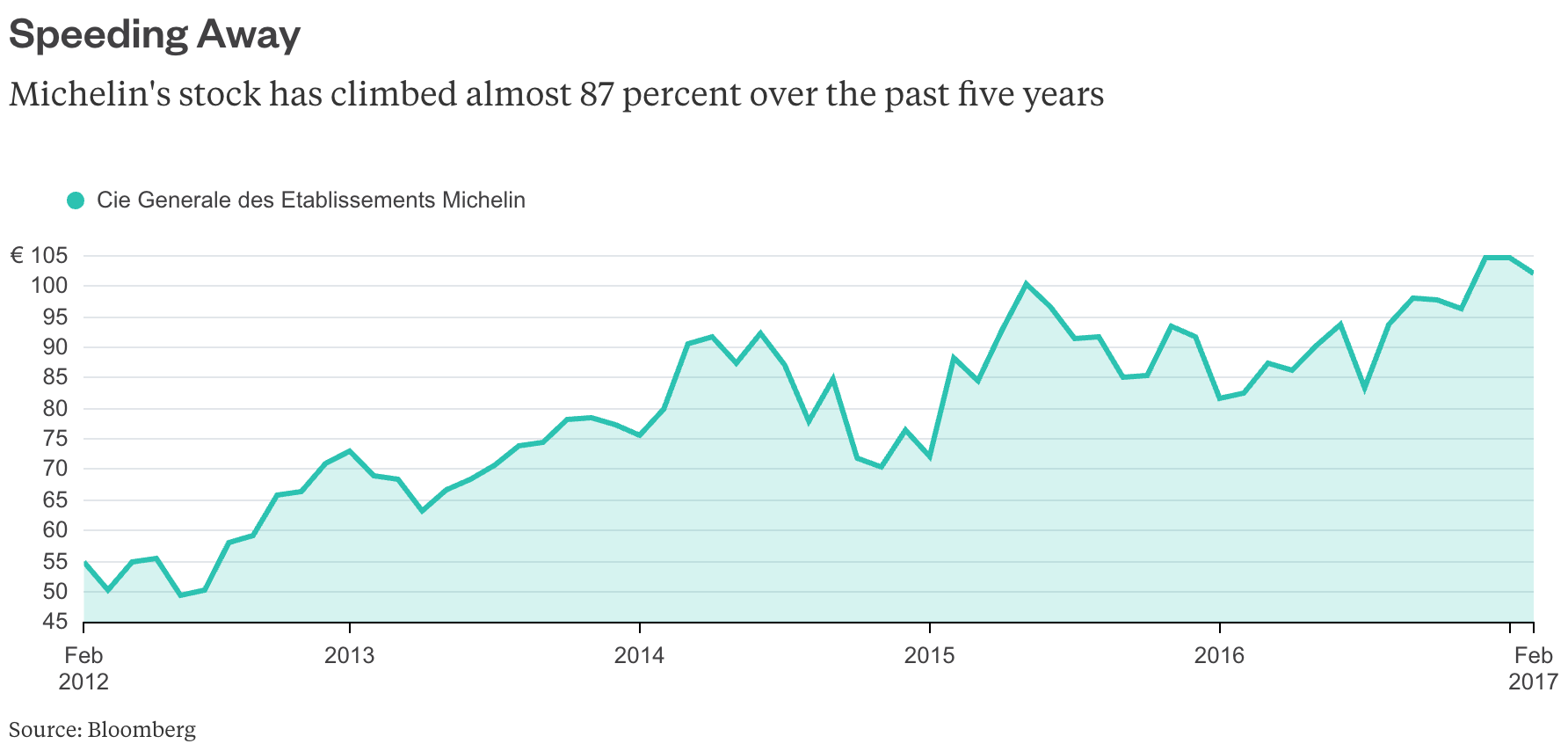

A convertible investor is (reasonably) assured of getting their money back, and could make a decent profit by being repaid in highly valued shares in the issuer. From the perspective of the issuer, convertibles are a chance to sell equity for more than the current share price -- assuming the stock eventually hits that level.

But Michelin and Fresenius have done something a bit cleverer.

Their $500 million and 500 million-euro ($534 million) offerings last month were structured to deliver investors a convertible-style return if their share prices rise. But any such gain will be paid in cash, not shares. So neither company will issue new equity if the bond "converts," nor will their shareholders get diluted.

In effect, the convertible investors have in each case bought an equity derivative that pays out if Michelin’s or Fresenius’s shares rise above a certain level, or otherwise gives them their money back. This has all been neatly packaged by the company and dressed up as a convertible bond.

It may all seem like a bit of a palaver -- but inefficient markets means that this convoluted process makes for cheap funding. The coupons on Michelin’s and Fresenius’s convertibles were zero. Investors were willing to pay a premium for Fresenius, so the yield will be negative. Michelin's deal likewise achieved a negative yield via some fancy footwork converting the proceeds into euros. Even after shelling out for the derivatives that deliver investors gains in their stock prices, it's more attractive for the issuer than a traditional bond of the same size.

How come this is possible in supposedly efficient markets? Surely the convertible investors should just buy ordinary bonds, which at least have a positive yield, and purchase options on the company shares themselves? The snag is that they probably aren’t allowed to: their investment mandate requires them to buy convertible bonds. End of story.

Today, demand exceeds supply, so convertible investors are tolerating seemingly onerous terms, according to people in the market. They are awash with cash from the redemption of past investments and that cash needs to be put to work. Plus if a convertible is likely to qualify for an index, the fund manager may have no choice but to buy, regardless of price. The goal of the end investor may be diversification not performance.

We’ve been here before. The first half of 2016 saw a mini boom in these so-called equity neutral convertibles when investors had excess cash they had to spend. Then it faded away.

Other companies might want to exploit the arbitrage while they can.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

To contact the authors of this story: Chris Hughes in London at [email protected] Marcus Ashworth in London at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at [email protected]