Italy’s recent political drama—and the financial markets’ response to it—highlights starkly that pockets of fragility remain in the eurozone’s much heralded improved economic prospects.

The key parts of the narrative are not unfamiliar, given the country’s long history of successive governments of limited longevity since World War II. An inconclusive election outcome in March put two populist, anti-establishment parties in the lead and after managing to reach a tenuous agreement to form a coalition agreement following two and half months of arduous negotiations, Italy’s president refused to approve a key member of the cabinet list presented to him, appointing instead an interim caretaker prime minister and raising briefly the prospect of new elections in July.

While the situation may be temporarily cooling down, largely as a result of intense political maneuvering after Moody’s warned the instability may lead to another downgrade of its debt, Italy’s saga is unlikely to disappear from the headlines in the period ahead.

A key tenet of the coalition government’s proposed economic measures was a demand that the European Central Bank “cancel” the 250 billion euro Italian sovereign debt that it has acquired in the context of its three-year-old asset purchase program.

Such a highly unusual stated objective was in good measure for the reason that Italy’s sovereign bonds were battered this week; the obvious fear was the possibility that the new government might force a restructuring of its remaining 2 trillion euro debt currently held by private investors. Ten-year Italian bond yields spiked to over 3 percent, having surged by over 170 basis points in the last few weeks, and credit default swaps on the country’s debt surged earlier in the week in a dramatic demonstration of such fears.

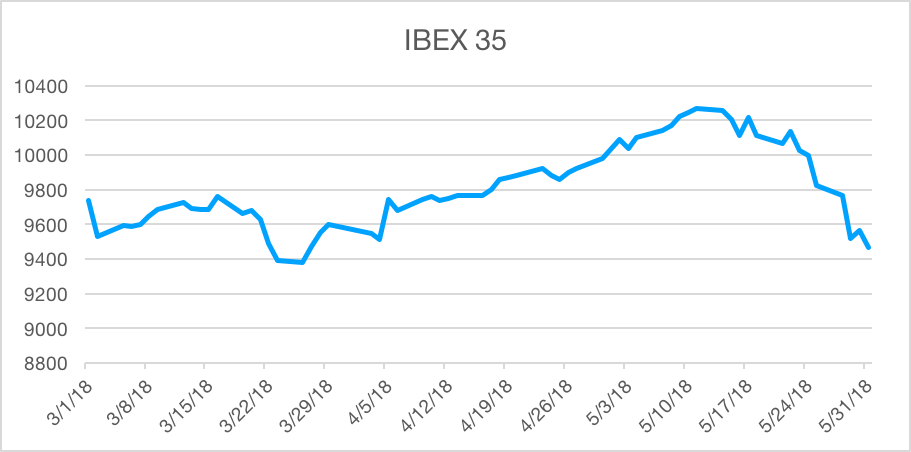

Compounding the anxiety was a parallel development playing out in Spain, where the government of Prime Minister Rajoy was ousted after facing a parliamentary no-confidence vote, which leaves the country with a socialist prime minister leading a highly disparate coalition of several parties. That hardly suggests an outlook of political stability and raises the likelihood of new elections in the coming months, which (until now) the dominant center-right party would severely weakened thanks to an array of corruption scandals.

Spanish government bonds were punished just as hard this week as Italian ones and the IBEX 35 Index suffered a comparably severe sell-off as Italian stocks.

In other words, both the third and fourth largest economies in the eurozone are entering a period of political uncertainty, with Italy being in the most precarious position of the two, given the confrontational attitude of the two anti-establishment parties that appear to be in the driver’s seat for now.

Basic rules of political realities imply that neither the Italian Five Star nor the far-right League party can afford to alienate their voter base by backtracking on their ample and repeated election promises of challenging the established structures of the EU, even though they don’t advocate an exit from the eurozone for the time being.

This implies that, either in its current configuration, or as a result of new elections, any coalition government run by those two parties is likely to keep the EU structure on its toes, with the potential of intermittently rattling financial markets. Such a dynamic is likely to fuel risk-off bouts in European risk assets in the coming months, which points to the need for a degree of caution vis-à-vis the bloc’s equity markets.

As a direct result, investors who need to remain in euro-denominated fixed income assets should gravitate toward the safe haven status of German bunds and, to a lesser degree, French bonds.

The market turmoil that Italy’s political situation set off has fueled some comparisons with the sovereign debt crisis that swept the eurozone in 2010-2012. While such a comparison is intuitively inevitable, the odds that the current anxiety can reach the proportions of the previous episode are not high at this point, with negative short-term rates, a more proactive ECB and a massive amount of liquidity already in the financial system, all acting as a cushion against a worst-case scenario.

However, the sheer size of the Italian economy and its debt, as well as the decidedly antagonistic attitude of the two key parties in the country, argue against the current tensions subsiding safely in the period ahead. What the last couple of weeks have also demonstrated is that the wounds from the 2010-2012 eurozone debt crisis have not healed completely and the risk of contagion to the markets of other key economies (Spain and, to an extent, Portugal) remains acute.

U.S equities are in a somewhat less vulnerable position than European markets to weather a moderate risk-off event, given the still positive domestic economic outlook and healthy corporate earnings. However, the concept of “risk-off” is always a matter of degrees and no asset class that is inherently risky would stay immune to a more sustained turmoil in European markets if things take a turn for the worse there.

The latest events have also shown that investors should not view U.S Treasurys as being on an inexorable path toward 3.5 percent or more in the months ahead.

Treasury yields do not move in a vacuum, and the status of the U.S. government debt market as the primary beneficiary in periods of anxiety elsewhere has been spectacularly validated once again, with the 10-year yield falling by over 30 basis points at one point this week since their peak in mid-March.

Following a long career as a professional economist in the financial markets, Anthony Karydakis currently teaches at the Economics Department of NYU’s Stern Graduate School of Business. He holds a doctorate from The Sorbonne in Paris.