By Rachel Evans

(Bloomberg Markets) --Leighton Shantz had barely begun managing part of the $26 billion pension fund for Texas state employees when he got a crazy idea.

The fund’s floundering investment-grade bond portfolio was occupying his undivided attention, its strategy clearly broken. No matter what he tried, the securities couldn’t deliver sufficient yield or liquidity. He knew he had to get rid of them; he just wasn’t sure how. The time-tested rules for fixed income, which Shantz had honed for years as a managing director at Lockheed Martin Investment Management Co. and as a money manager for Tennessee’s retirement system for teachers and state employees, no longer seemed to apply.

As he analyzed the broader portfolio over the summer of 2012, it dawned on him that exchange-traded funds, which were becoming increasingly popular investing tools, might prove useful. These funds needed thousands of securities just to exist. Perhaps they could take the bonds off his hands? Yet whenever ETFs came up in conversation with asset managers, they responded how a Texan might react to finding beans in his chili. “Every one of them commented on how stupid bond ETFs are,” says Shantz, 51. That response didn’t sit especially well with the contrarian. “I decided that either fixed-income ETFs were truly sensationally stupid—which didn’t explain why their assets were growing so fast—or there was much more to it.”

Shantz and his team of six began studying the funds. What they found intrigued them—so much so that in May 2013 Shantz forked over $1.35 billion of debt, or almost 20 percent of the fixed-income book, in exchange for shares in two of BlackRock’s investment-grade bond ETFs. It was a bold move for the Employees Retirement System of Texas, an institution that had only one small trade in bond ETFs under its belt when Shantz joined. When he later explained the maneuver at an industry event, peers and competitors told him that he was risking his reputation and that he’d gone mad. “They were absolutely convinced that I was a fool,” he says. “In a market dislocation, [they said,] these things would blow up, leaving me in a smoking heap in the ditch.”

That wasn’t just fear of the unknown. When the U.S. housing bubble burst in the mid-2000s, the price of some ETFs diverged sharply from the value of their underlying bonds. Given that these funds had since become more sophisticated and complex, some wondered whether they could walk through the fire of a global financial crisis. But Shantz and his portfolio have yet to find said ditch. Indeed, they’re both alive and well, with the credit book returning an annualized 5.3 percent over the last three years, beating its benchmark by 60 basis points. “It wasn’t until it was all done that you could breathe in and go, ‘Well, that was awesome,’ ” he says.

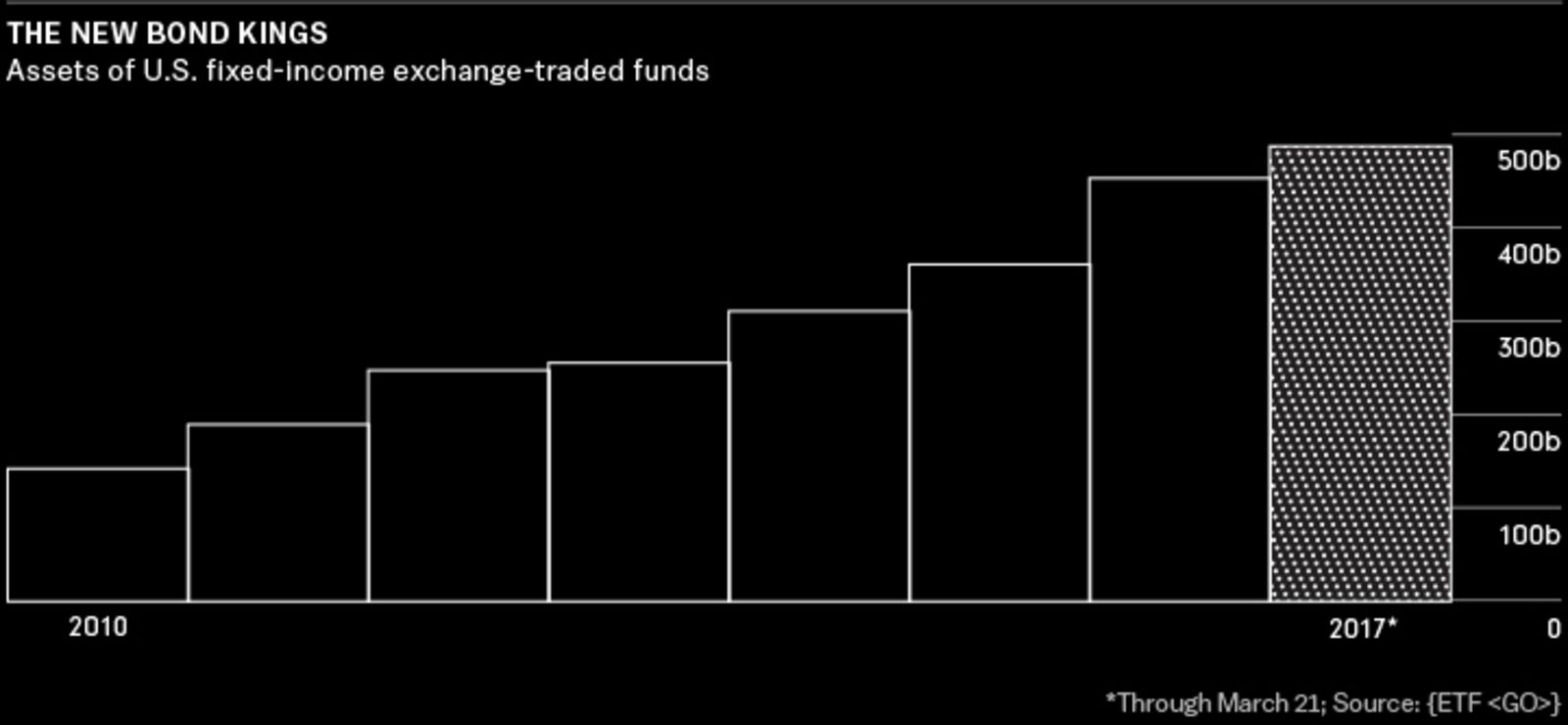

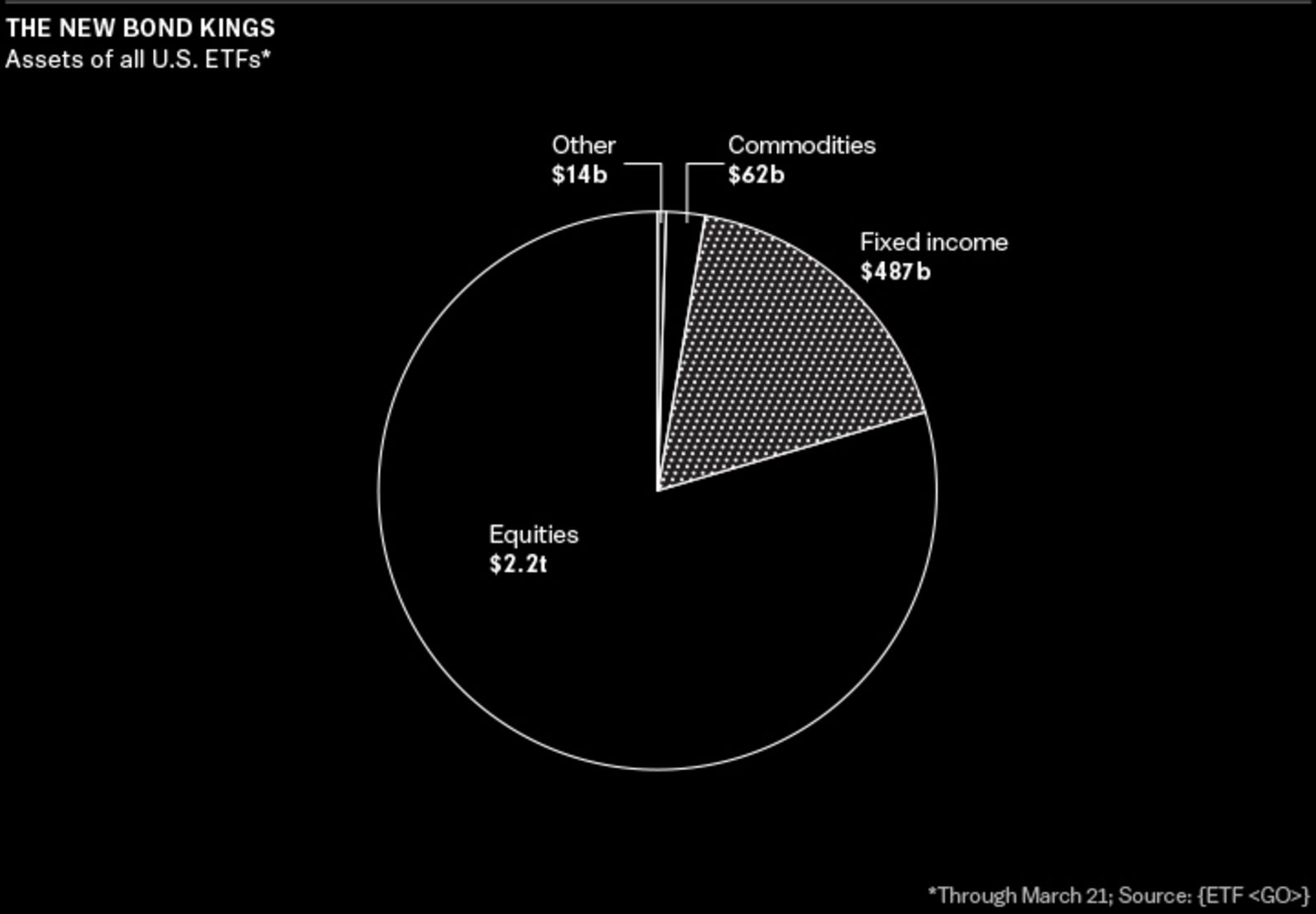

And the once-esoteric debt ETFs he used? They’re colonizing swaths of investor money that bonds used to rule alone. In pension plans, endowments, and mutual funds, they’ve grown as liquid alternatives to cash and temporary holding pens for capital, and as trading tools. Bond ETFs around the world are swimming in more than $700 billion of cash, with about $480 billion of that in the U.S. Although those sums are a drop in the bucket compared with equity ETFs, which account for about 80 percent of the $2.8 trillion U.S. market, debt funds are growing at a faster clip than all asset classes other than commodities.

Every bond powerhouse from Pacific Investment Management Co. to DoubleLine Capital has started funds to get in on the action. More shares in a BlackRock high-yield debt ETF were traded on its busiest day last year than shares in Wal-Mart Stores, Exxon Mobil, or American International Group during the same session. By contrast, similar bonds typically trade fewer than 100 times a day.

This rapid explosion of “Debt 2.0” has spurred dislocations and mutations in the market. Regulators worry that ETF brokers can’t keep pace with investor appetite for the funds. Some ETFs flirt with allowing cheaper assets into their portfolios so they grow faster than their competitors. And the products are getting more and more complex. But none of this has slowed their acceptance by the financial community. “It’s gone viral,” Shantz says.

Turning bond ETFs into the next Grumpy Cat was far from Stephen Laipply’s mind when he got the call from Texas in early 2013. Laipply had welcomed Shantz to BlackRock’s San Francisco office a few weeks before and was impressed by the fund manager’s thoughtful questions about ETFs. Now Shantz was back with a proposal.

A flood of easy money spilling out from the Federal Reserve had lifted company debt almost 10 percent in 2012, according to the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Bond Index. Investors had two ways to join the party via ETFs: They could either buy shares from existing owners on the stock market, the way they would with Apple Inc. or General Electric Co., or they could ask the ETF manager to create new shares for them. To create shares, an investor could pay in cash or “in kind,” acquiring and delivering an agreed-upon smorgasbord of securities to the fund, which the fund would then absorb and use to support the issuance. A middleman, usually a bank or broker, facilitated the switch.

Shantz wanted to explore an innovative version of the second route: using his book of investment-grade debt to buy the shares. Laipply had seen this type of portfolio trade only once before, nine months earlier, when he’d swapped 4,000 bonds from a large pension fund for shares in BlackRock’s flagship ETFs. He started picking through Shantz’s selection of securities to determine which bonds might fit into their ETFs. “There were hundreds of bonds,” Laipply says. “We went through a process of just looking at the potential candidates and seeing how they could map onto our ETFs.”

Those names were then sent to BlackRock fund managers, who made the final call on whether to accept or reject the offerings. A little more than half the bonds were a match. Elated, Shantz handed over the debt in exchange for shares in two investment-grade ETFs. Just like that, step one was complete.

But for Shantz, that wasn’t the end. The pension plan needed bonds, not these ETFs, and he’d settled on a mix of junk debt and Treasuries. So after lying low for three months, Shantz quietly arranged step two: selling the ETFs in the secondary market to exit his position and free up capital. By October he’d halved his exposure. By December the shares were gone. Shantz had his cash—and all without roiling the price of the ETFs. “We didn’t want to show up every day looking for bids,” he says. “You can go into ETFs and buy or sell exposure in size and never tip your hand to anybody.”

That versatility is part of what makes ETFs an attractive proposition for money managers frustrated with the clubby world of traditional debt trading. Rules implemented after the financial crisis have crushed the banks and brokers that previously oversaw bond trades, curbing their inventories and manpower and making large trades a laborious process that nimbler competitors can exploit.

ETFs offer a speedier, cheaper alternative. The difference between the price at which traders are willing to buy or sell a mainstream junk-bond ETF is about 1 basis point, considerably less than a spread of about 45 basis points to trade the underlying basket of bonds. The fee to create ETF shares is typically less than $1,000. In tumultuous markets, the funds are a safe house for investors, allowing them to remove baskets of bonds from their balance sheets in return for highly tradable equity instruments that they can switch back into debt when markets calm down. Others buy ETFs to earn income on capital they’re waiting to allocate elsewhere. And still more follow Shantz’s example and use ETFs as a tool to adjust their portfolios. “It’s happening every day at some level and in some form,” says Damon Walvoord, co-head of the ETF group at Susquehanna International Group LLP. “It still has a long way to go before it’s an everyday tool for bond managers, but it’s moving in that direction.”

Such a dramatic transformation of the debt market brings challenges as well as opportunities. Regulators fear that share creations could falter if even one or two middlemen who lead these trades quit. The Securities and Exchange Commission needs to review the role of these gatekeepers, Commissioner Kara Stein has said.

Difficulties sourcing debt to create ETF shares and managing that risk—particularly overnight—have already pushed some middlemen to stick to cash creations or hand over tricky requests to their competitors. The likes of Susquehanna have dedicated bond ETF traders, but debt and equity teams at some other shops remain divided. The creation process they administer—which is unique to ETFs as an asset class—is also fragmented. Although some bond ETFs demand a basket of securities already found in the fund, others require a portfolio of debt that’s merely similar. The latter makes for a more liquid ETF that’s easier to create, particularly for portfolio trades, but it also incentivizes submitting the cheapest qualifying securities to the fund. ETF managers wanting to increase their assets must walk a fine line between accepting them and diverging too far from their mandate. “We’re evaluating them very closely, but the execution potentially is not as good as doing it yourself,” says Gregory Peters, who runs Prudential Financial Inc.’s flagship Total Return Bond Fund. “I’m not an ETF hater by any stretch of the imagination, but those are some of the challenges we face as an active bond manager implementing ETFs into the strategy.”

Many other money managers have made their peace with debt ETFs and are weaving them deeper into their books. BlackRock gained 64 institutional users of its bond ETFs last year, while almost 70 percent of the 100 pension funds, insurers, and investment advisers surveyed for a Greenwich Associates LLC report last September said they’d increased their use of the funds over the previous three years. Investors that have already embraced portfolio trades are now utilizing ETFs in lieu of options, swaps, and futures. Instead of entering total-return swaps, they’re finding similar exposure in an ETF. And rather than using credit default swaps, investors are hedging their debt holdings with help from options on ETFs. Exchange-traded funds have also allowed investors to bet against entire markets rather than short individual securities. The funds are typically cheaper and require less balance sheet space or collateral than buying a derivative.

All of that seems a world away from the stakes Shantz faced using ETFs in 2013. Then, his reputation was on the line; now he uses them almost casually to respond to the needs of his portfolio—instantly boosting exposure to a hot sector or ditching a clutch of unattractive bonds. “There are some people who aren’t that bright and would rather fail unconventionally than muddle along conventionally,” he says. “I guess I’m one of those.” —Evans covers ETFs for Bloomberg News in New York.

This story appears in the April/May 2017 issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine.

To contact the author of this story: Rachel Evans in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Joel Weber at [email protected] Eric Weiner