When we all discuss rising deficits, the natural inclination is to worry over their bearish impact on interest rates. The logic is reasonable from several perspectives. First, there’s more to something which tends to depress its price (assuming steady demand) and anticipation of lower prices as supply is seen mounting. Second, in the case of Treasurys, presumably more debt means stimulus is coming in some form the economy might not otherwise get. True, more debt due to a revenue drop in a recession is a separate event, but a distinct one, as they typically don’t last and the deficit narrows in a recovery.

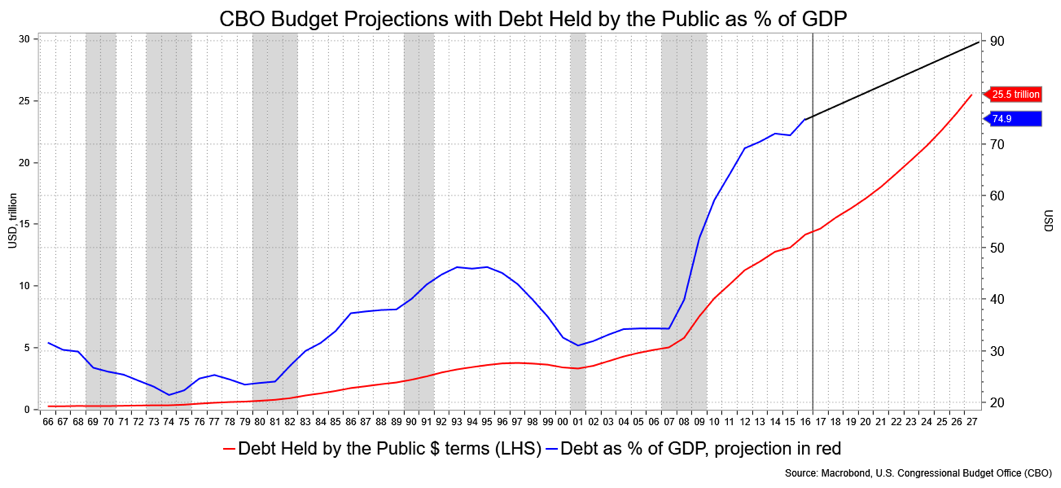

The U.S. is arguably in pretty good shape—low unemployment, a steady GDP—so that a big deficit explosion for fiscal stimulus doesn’t seem quite necessary or, many will argue, prudent. That’s especially so when the budget deficit is otherwise going to rise sharply per CBO budget projections anyway and those projections came before the current tax reform ideas were put forth.

In short, the deficit situation is looking really bearish for Treasurys. Or is it?

The chart above is for the record. It shows the current state of the budget deficit as a percent of GDP with a forecast to 2027 and the overall dollar amount. The CBO offers real GDP growth of about 1.8 percent for the next 10 years in some context and Potential Labor Force Productivity growth of about 1.3 percent. These seem reasonably conservative. Note that Debt as a percent of GDP is 74.9 percent today going to 90 percent with all things being equal, i.e., no deficit-boosting tax plan. That’s debt held by the public. The overall federal debt today is about 106 percent.

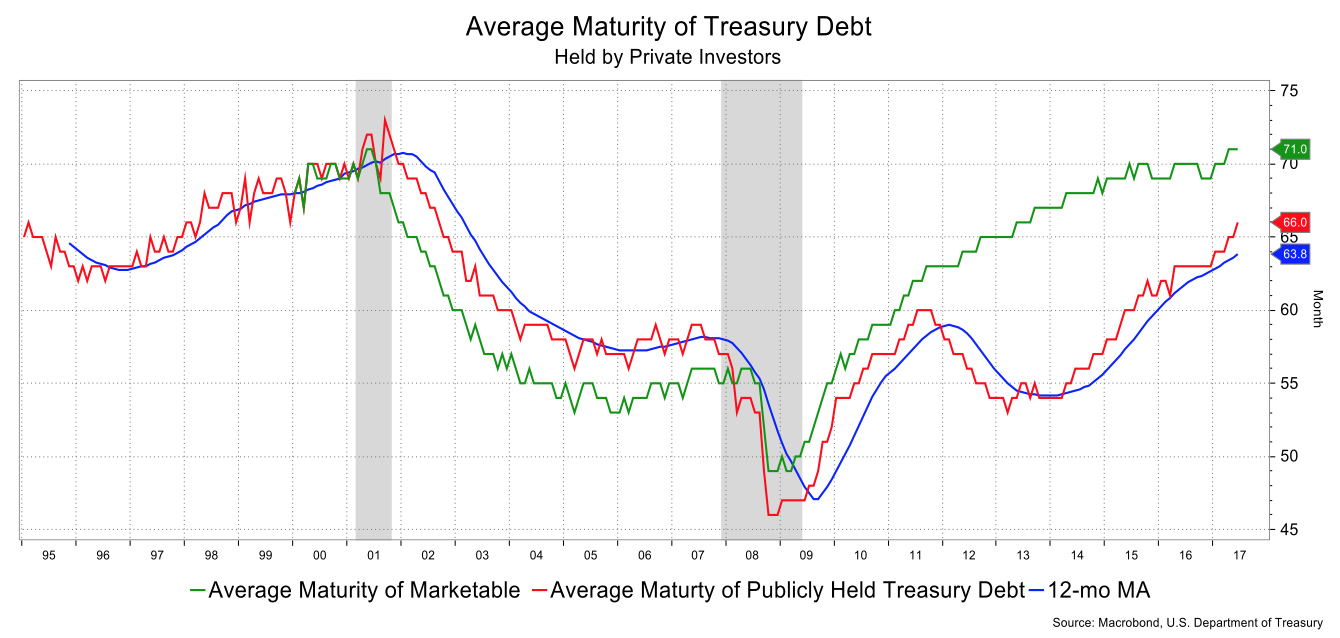

Note, too, that the Average Maturity of Treasury Debt has been rising and stands at 66 months for that held by private investors. This may not be entirely accurate; Treasury’s most recent report to TBAC has it closer to 71 months and projected to rise to near 82 months in 10 years. Assuming that the projections hold, there will also be a larger amount at the longer-end relative to today. That does not anticipate adding 40-year or longer debt which has been hinted at by this administration and, in any event, is something I anticipate if for no other reason than to keep pace with overseas pension interest and issuance in other sovereign markets. But either way, you get the picture: a lot more Treasurys and a lot more duration. See the charts at the end of this section lifted from the latest TBAC offering on the subject.

So getting back to my provocative effort above, is this really bearish for interest rates?

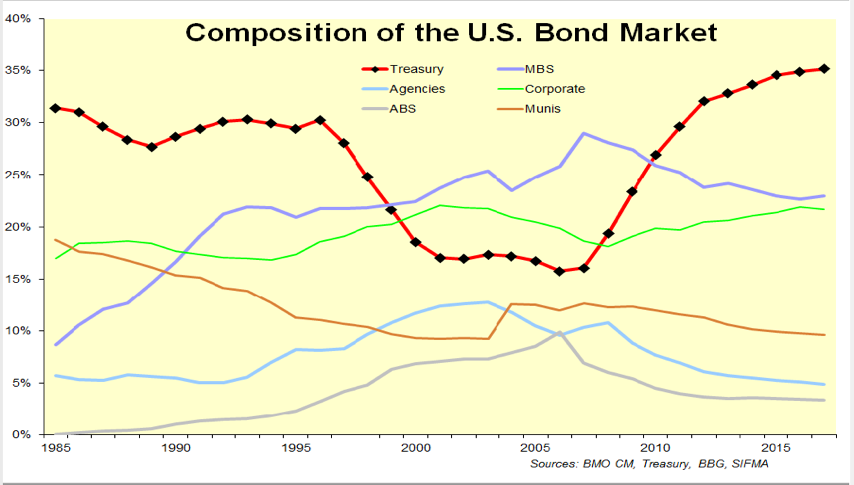

Well, simply, it relates to the structure of the market. That is, if the weighting of Treasurys as an asset class is going up relative to others, then an index investor will need to buy incrementally more Treasurys to keep pace. In other words, if the market currently has a 36 percent weighting in Treasurys and that’s rising, to say, 40 percent, in a few years investors will need to buy more Treasurys. I don’t think there will be much of an argument there. Over the last several years investors have overweighted other asset classes, especially credit, giving the low volatility, relative steady rate for the environment and incremental spread. Thus, the starting point is already underweighted as a growing asset class.

The chart below was provided by Ian Lyngen and Arun Kohli over at BMO Capital Markets. (This is something Ian and I put together conceptually when we worked together for over a decade and so I take a little credit for the idea.) What it shows is the current market structure or, in essence, a snapshot of the taxable bond market to illustrate my point. Between the rising deficit, the risk of a rising deficit with tax cuts and the Fed’s goal to balance sheet reduction, it’s a safe bet that Treasurys are going to go up in this chart.

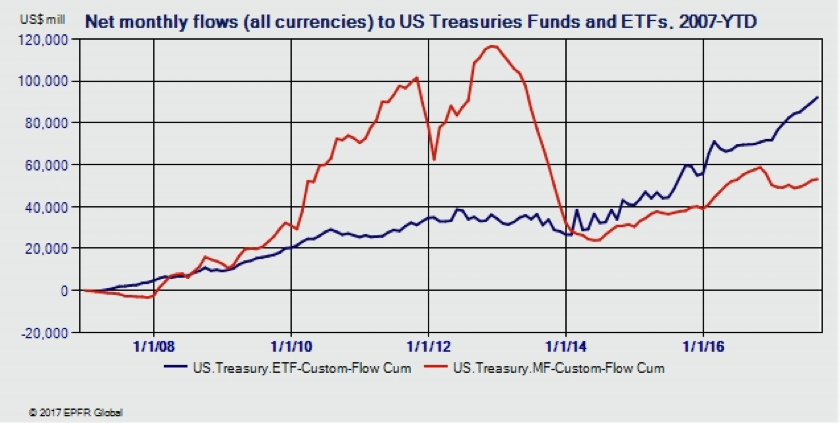

Now, add to that idea the increasing average maturity of Treasury Debt and what you have then is both MORE Treasurys and MORE duration to buy to keep pace with changes in their benchmarks. I haven’t even touched on investor moves to more passive instruments, like exchange traded funds, to encourage such moves, but there’s that angle as well. The EPFR flow data certainly confirms the heightened demand for Treasury ETFs at the expense of mutual funds.

In short, yes I worry about increased Treasury issuance and increased duration; logic dictates that. However, there is a very strong offset that might balance out those worries or, potentially force buying that keeps deficit-driven bearishness at bay and the saga of lower for longer in play for years to come.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.