My 2018 Outlook provoked a discussion with one fund manager about the nature of productivity, or rather the rate of change in productivity.

The question was whether older workers are more productive than younger, less experienced ones, and if so, is there a drag on productivity, and thus wages, as baby boomers move on?

What provoked this was I’d written that older workers’ wage gains are slower to negative because they are less productive, less upwardly mobile, less geographically mobile, less demanding on wages, and more interested in flexible hours and health benefits.

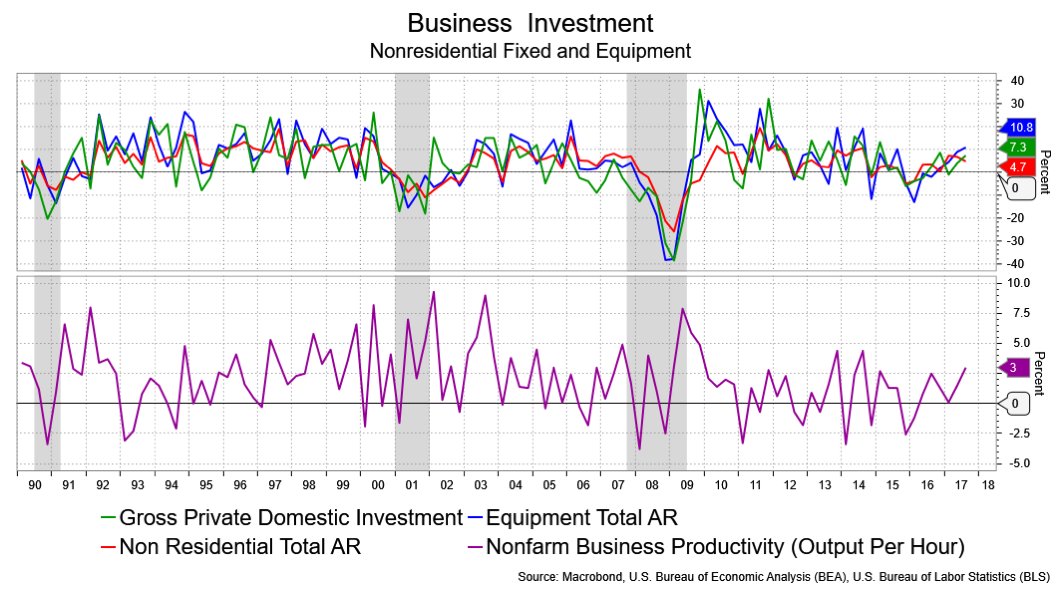

First, let me explain the productivity side of things. Productivity gains in this cycle have been pretty lame compared to other recoveries. In order to get GDP growth, we need both productivity improvement and population growth. Productivity gains have been tame, to say the least, in good part because investment has been missing. Getting back to my opening lines, there appears to be some renewed business confidence between global growth and the tax plan and so we may have the chance to see better business investment. The challenge is whether it will last.

I have my doubts given anecdotal evidence that corporations intend to pay down debt, engage in buybacks, and look to M&A with their tax windfall. But investing? Low on the totem pole. And if it does start, surely there’s the impetus for less in the way of humans (hiring and wage gains) and more to the long list of things robotic. Further, the accelerated (immediate) depreciation may not mean quite as much in a lower corporate tax rate world. Any impact may prove short-lived.

So back to my conversation with said fund manager. His take was that older workers are more productive, though their productivity growth rate diminishes (it does), while it will take younger workers, who are initially paid less, some time to move up the income scales. It’s a dilemma. The younger folks will add to productivity, but may not so much on wage improvement or widespread hiring.

Still, there has been improvement on the investment front and productivity has bumped to a two-year high. Hope springs eternal. The wage inflation aspect remains, however, somewhat elusive.

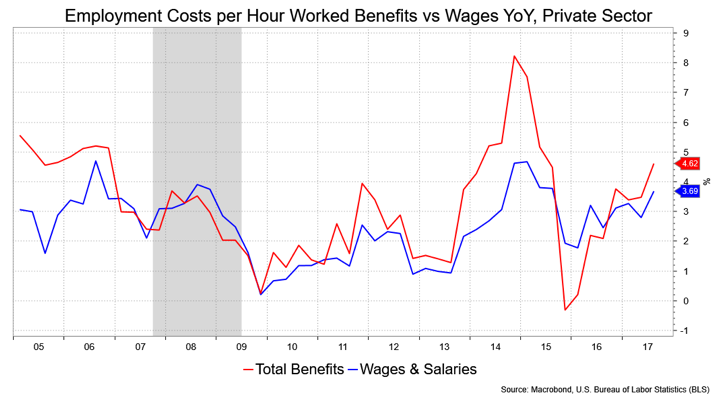

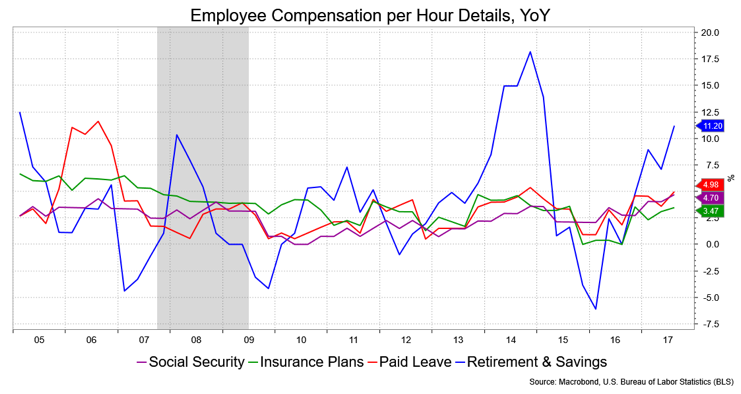

Related to all that is a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, “Vacation Perks and Retirement Benefits Are Propelling Worker Pay Packages.” The article notes that benefit costs are rising faster than wages, gaining 4.6 percent year-over-year vs. 3.7 percent. The spike in 2014-15 was about the Affordable Care Act. Benefits gains subsequently sank, but are on the rise once more; the article attributes that to an increase in paid leave and retirement benefits. Retirement benefits rose 11.2 percent YoY and paid leave gained 5 percent.

The hinted takeaway is that such benefit gains could explain the soft wages gains in recent years—benefits are gaining faster than wages. This would go a long way in explaining how low unemployment has foiled those looking to find wage inflation AND could reflect the needs and desires of an aging workforce.

This is what I alluded to in my response to that fund manager. “When I’ve looked into the productivity and age thing I find that workers reach a point where their productivity gains slow and start to diminish. I presume that’s because they’re: 1) in a role whereby they are in a routine and that’s merely steady, 2) they require extra time off for health and other things, 3) get more time off for vacations and the like, 4) are less ambitious, and 5) are less mobile so, again, in more stagnant roles, I know their incomes reflect this.”

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.