In the week just passed, the bond market continued its bullish recovery, though with far less of the fundamental impetus that followed the prior week’s litany of economic disappointments.

It was black-out week ahead of a Federal Open Market Committee meeting where nothing much was expected to happen, certainly no change in policy and, probably, no insight into the timing of balance sheet moves. We won’t even get updated dots or forecasts from this coming meeting. I mention this as an afterthought; Fed Fund futures barely budged this week.

That all makes sense, given the lack of inputs and the calendar. It also makes me a bit more circumspect about the pace and depth of further gains. The fundamental angle that helped start things holds, but no range-breaking antics just yet.

The Financial Times recently had a story, “Central bank action propels bond market crash worries.” that caught my attention. It focused on a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey of investors wherein 48 percent of respondents cited central banks as being too stimulative—the most since April 2011. Further, the biggest vote-getter for tail-risk concerns was the bond market, with 28 percent saying they “feared” a correction.

It’s the nature of surveys to find a common element and derive something from that. I write that because the second-biggest risk cited by the survey, with 27%, was a policy error by the Fed or the European Central Bank, which presumably would be a problem for risk assets, and economies more generally.

I see a conflict here. Too stimulative and bond yields surge; policy error when central banks are talking more hawkishly and, I’d guess, bond yields don’t surge.

My take is that the risk is not for a surge in bond yields, but rather that a modest rise—say, to the recent highs in the 2.60s for 10-year Treasury—will prove a bigger problem for risk assets and a buying opportunity for Treasuries. Of course, it all depends on how we get there. If it’s based on inflation—of which there is little sign of a pickup in the coming months—then I’m simply wrong. If it’s from the start of balance sheet reduction or QE reduction overseas, I think a retreat in yields will prove short lived.

What I think is in the process of slowly being discounted—and a greater threat to risk assets—is the dilution of the broad GOP/Trump economic agenda. Combine the latter with a temporary rise in rates and you’ve got a story that is supportive to the Treasury market. At the very least, it keeps longer yields in the sort of range we’ve seen since the end of last year.

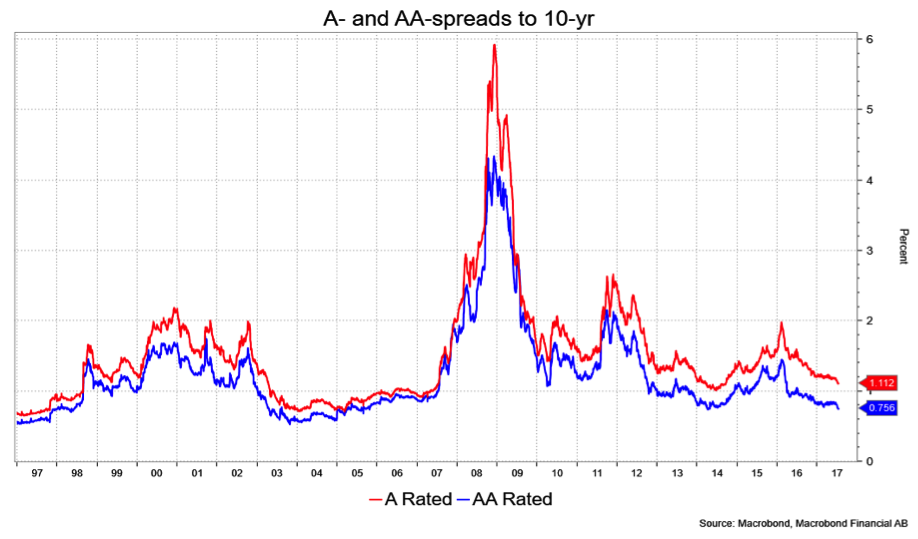

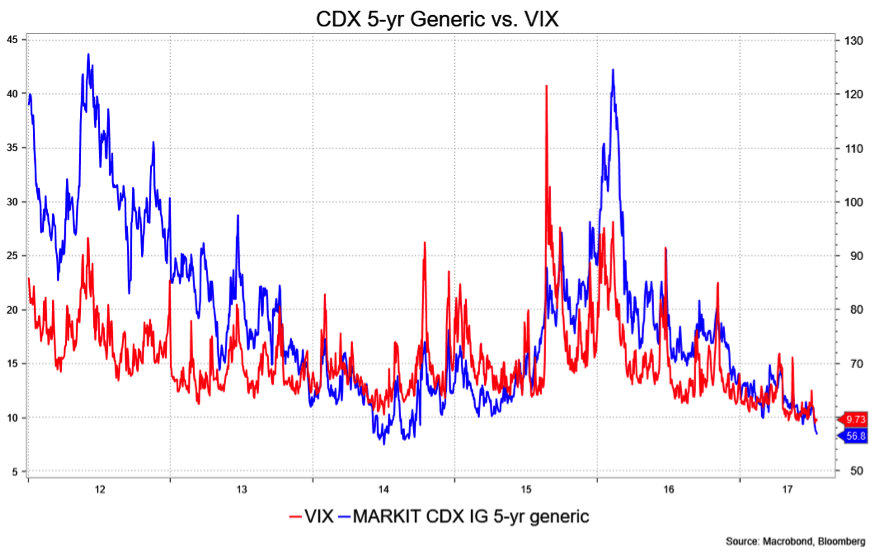

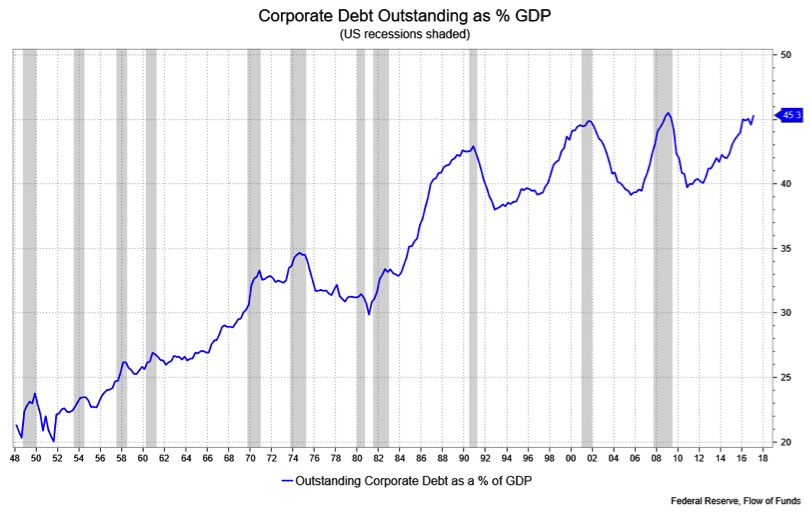

Here is a series of charts that illustrate the state of things, i.e. corporate spreads and corporate indebtedness. Keep the valuations implied by the first two charts (A- and AA-spreads and the VIX vs. CDX 5-yr IG) in mind when looking at the third chart, which shows outstanding corporate debt as a percent of GDP.

State Pension Mismatch Problems

Wilshire Consulting released a report in June stating that state pension funds’ funding ratio (the percent of assets vs. obligations) had dropped to 69 percent in fiscal year ending June 30, 2016. The same study showed that 97 percent of state retirement systems “have market values less than pension liabilities, or are underfunded.”

On average about 65 percent of assets are allocated to stocks, including real estate and private equity, 25 percent to fixed income, and the balance to a mix of non-equity assets (like hedge funds). Wilshire estimates a 10-year expected return of 6.4 percent, which is 1.1 percent less than the median liability discount rate of 7.5 percent. Hmm.

This mismatch must be a problem at some point. Is any shortfall made up by higher taxes or does it come from reduced benefits? Or, do pension managers invest in higher-returning, but riskier, assets? They certainly have been doing the latter as exposure to U.S. stocks has fallen in the last 10 years (from 42.3 percent to 27.4 percent) in favor of real estate, non-U.S. stocks and private equity.

David Ader is chief macro strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.