By Stephen Gandel

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --The problem with passive investing, I promise, is worse than you think.

There has been plenty of anxiety on Wall Street about the rise of indexing and ETFs, known collectively as passive investing, with the number of indexes exceeding the number of stocks. Academics and financial pundits have posited that index investing may be pushing up consumer prices, though there are also critics who are skeptical that it kills competition. But if your concern about index investing starts and ends with the notion that some fund managers will lose their jobs, that you might have to pay slightly more for an airline seat, and that it's a small price to pay for lower fees in your 401(k), your conclusion might be incredibly wrong.

The rising stock market, and the fact that index funds have beaten every variety of their active rivals, could be blinding investors to increasing damage that indexing is already doing, and could still do, to the market and the economy. The real concern is not just that actively managed funds could disappear but that the entire market could be left for dead.

Earlier this summer, another media outlet published a popular and debated article on the complete calamity that could happen if climate change continues on its current path. So, given that these are the dog days of summer and that even a CEO-led revolt against President Donald Trump can't shake the market, we decided to give passive investing the worst-case scenario treatment.

Like climate change, the forces driving investors to passive investing may be too far along to turn back. The velocity toward index-driven dystopia appears to be increasing.

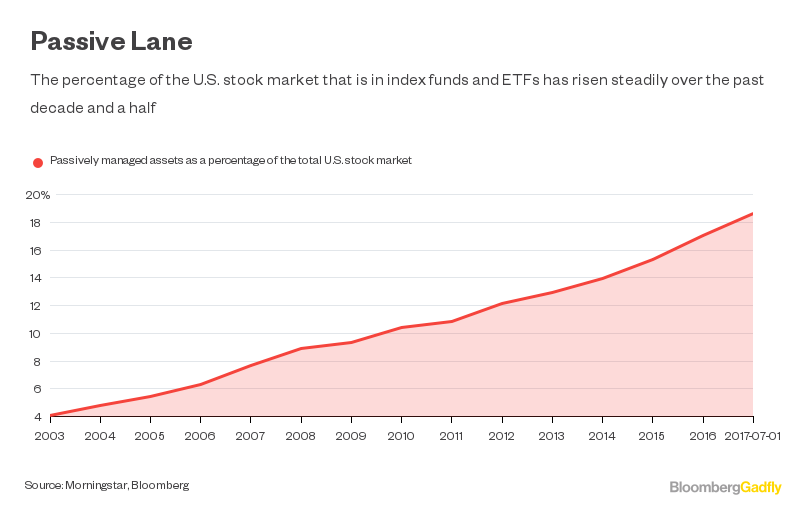

Indexing has, of course, been around awhile. Nonetheless, earlier this summer, this statistic from a Bank of America report seemed to catch many by surprise: Funds run by Vanguard, the giant index fund company, now own at least 5 percent of 490 of the S&P 500 companies, up from just 115 seven years ago. The same report said that passively managed assets as a percentage of all managed assets had risen to 37 percent. Soon afterward, a report from Deutsche Bank predicted that half of all assets would be passively managed by 2021. While the reports inflated the figures by looking at mutual fund assets instead of all assets invested in the U.S. market, what is striking is that at 19 percent -- the total amount of the U.S. stock market owned in index funds or ETFs at the end of July, according to data from Morningstar and Gadfly calculations -- the effects of passively managed funds are already being felt. Imagine when it actually gets to 37 percent, or 50 percent.

The Stock Market Could Get a Lot Riskier

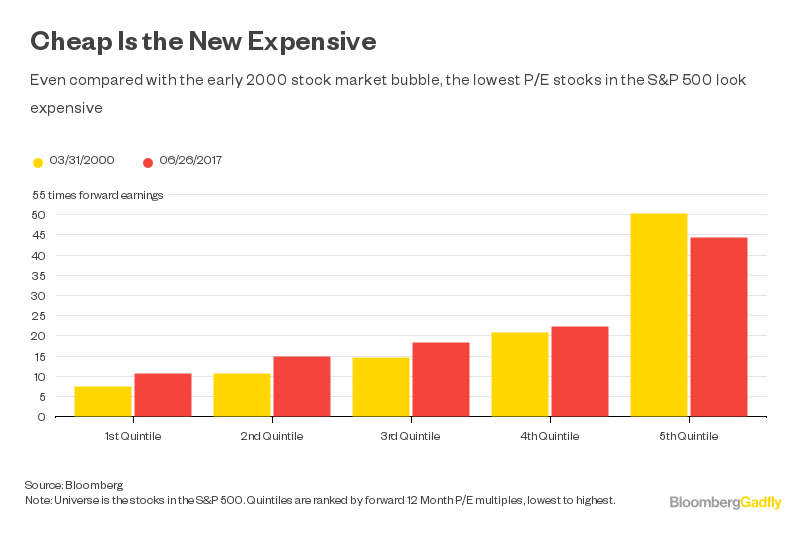

Passive investing, which was supposed to make it easier for the set-it-and-forget-it set, could make the market intolerable, especially for individuals. The idea of investing in a diversified portfolio is that you get a basket of stocks. When some are expensive, others are cheap, and that can offer protection when the stock market drops. Index funds, though, are pushing up the value of all stocks, leaving few safe havens. At the height of the dot-com bubble, for instance, when the most expensive stocks in the market, mostly tech shares, were trading at 50 times earnings, the cheapest stocks by quintile were trading at less than 8 times earnings. The market's cheapest 20 percent of stocks are now trading at nearly 11 times earnings and becoming more expensive.

But the real problem will be volatility. A few years ago, some investors used to joke that if the market was totally passive, not only would there be no volatility, there would be no stock movement, at least not for individual stocks. The market would move in lockstep when people bought or sold an index fund.

But that's not how it's playing out, or likely will. The Bank of America report on indexing last month pointed out that while the market overall seems smooth at the moment, there has been a recent spike in the volatility of stocks that are owned largely by ETFs and index funds, probably because of liquidity. With fewer shares to trade, once more are locked up in ETFs and index funds, even small trades could cause bigger price swings. In the six months ending in May, Bank of America found that the average volatility of the 100 most passively owned stocks tripled to 45 percent above the rest of the market.

The CBOE Volatility Index has averaged 20.5 over the past decade. If it were 45 percent higher, that would bring it to nearly 30, or 20 percent higher than where it was at the peak of last year's high-yield debt concerns and not much lower than where it was during much of the worries about European debt in 2012. And that would be the average level of volatility based on a market where just 20 percent of all equity is indexed. The VIX traded as high as 80 during the financial crisis, which means already at times of stress the VIX, which is called the market's fear gauge, could get up to 120, or about 10 times where it is now.

Income inequality

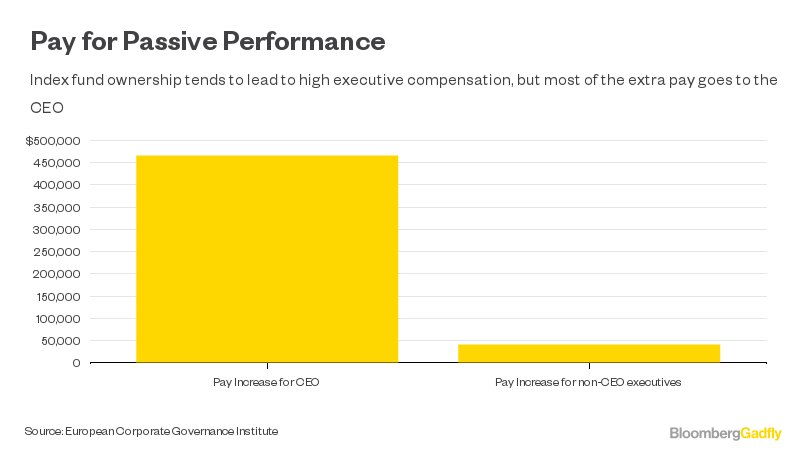

Income inequality is already a problem in America. Index funds are making it worse. A study published last year by the European Corporate Governance Institute examined the compensation of the top five highest paid executives for each company in the S&P 1,500 plus 500 other public companies. It found that executives at companies in industries with high common ownership were paid 25 percent more than executives in industries with lower levels. What's more, CEOs received most of the excess pay gains. After controlling for other factors, the study found that CEO pay tends to jump 10 times as much as the pay of the other top executives after a rise in passive ownership.

The compensation study also found that as index fund ownership of a company rose, the pay of top executives was more closely tied to the performance of the industry than that of their own company. The higher the level of passive ownership, the study found, the more a sort of reverse competition started to dominate an industry. The fallout: If the market were mostly index-owned, executives might actively work to help their rivals, at least if they wanted to see their paychecks grow.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the current ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay is 271 to 1. If index funds come to dominate the market, CEOs could soon make $338,000 for every $1,000 paid to the average employee.

-- Coming on Tuesday: Shrinking R&D and disappearing IPOs

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

To contact the author of this story: Stephen Gandel in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]