By Noah Smith

(Bloomberg View) --In the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, Calvin asks his dad how engineers determine the weight limit on bridges. The dad answers that they do this by driving heavier and heavier trucks over the bridge until it breaks, then rebuild the bridge after discovering what it took to break it.

This isn’t how engineers actually figure out the safety specifications of bridges -- since they know a lot about how physics works, they can predict how much it would take to break a bridge without actually breaking it. But the same isn't true in the financial world. No one knows the basic laws that govern asset markets, so there’s a tendency to use new technologies until they fail, then start over. Calvin’s dad was effectively describing the process by which we test financial innovation.

Mortgage-backed bonds are a good example. The original idea of securitization of mortgages was diversification -- instead of lenders taking on the risk of individual houses or geographic concentration, they could effectively own a little piece of each housing market in the country. In theory, that would make it safer to lend to homebuyers, thus lowering mortgage rates. But securitization had a lot of bad effects on mortgage markets that the basic theory ignored -- it hurt the quality of mortgages, and led to banks hiding risk rather than reducing it. It took a huge crisis to teach the financial world the dangers of securitization. Other examples include portfolio insurance, which helped cause the 1987 stock market crash, and credit default swaps, which also played a role in 2008.

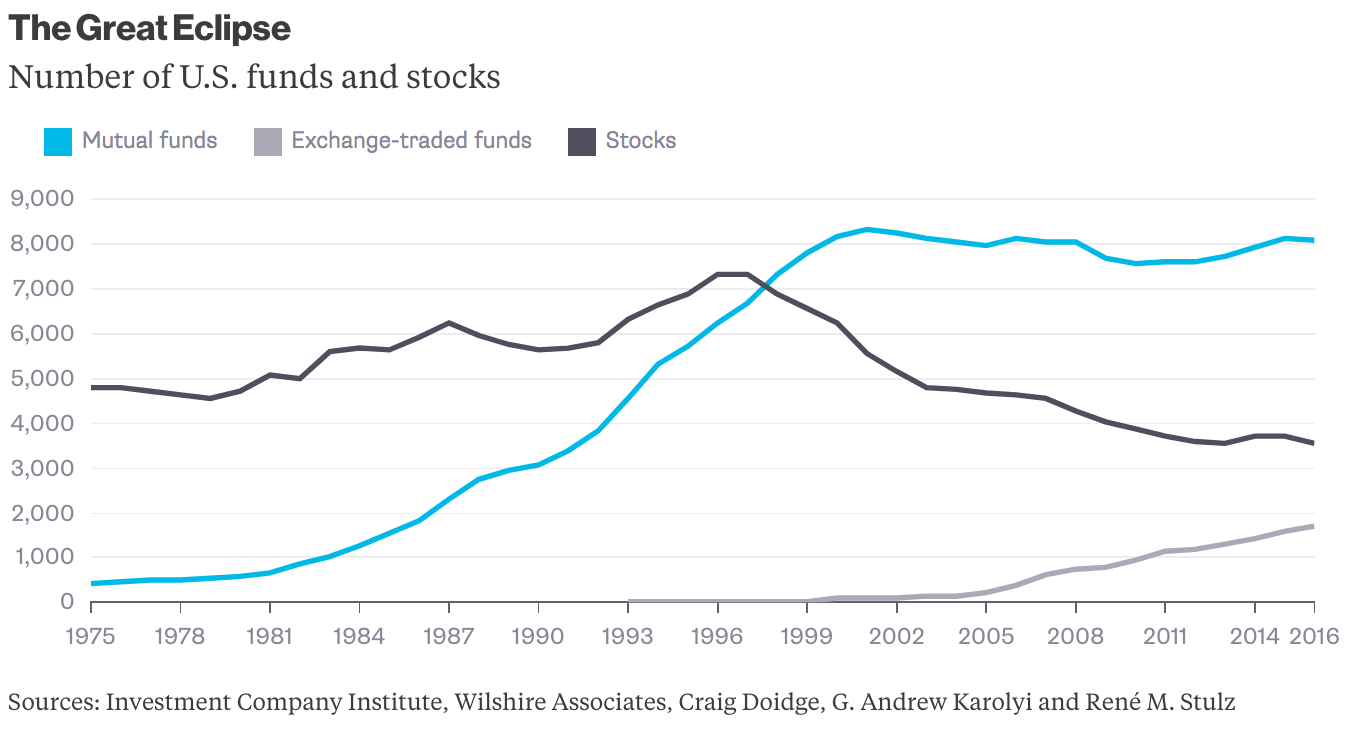

In the years since the crisis, financial markets have started to be transformed by a new innovation -- exchange-traded funds. ETFs are still only a fraction of the stock market, but that fraction is rising steadily:

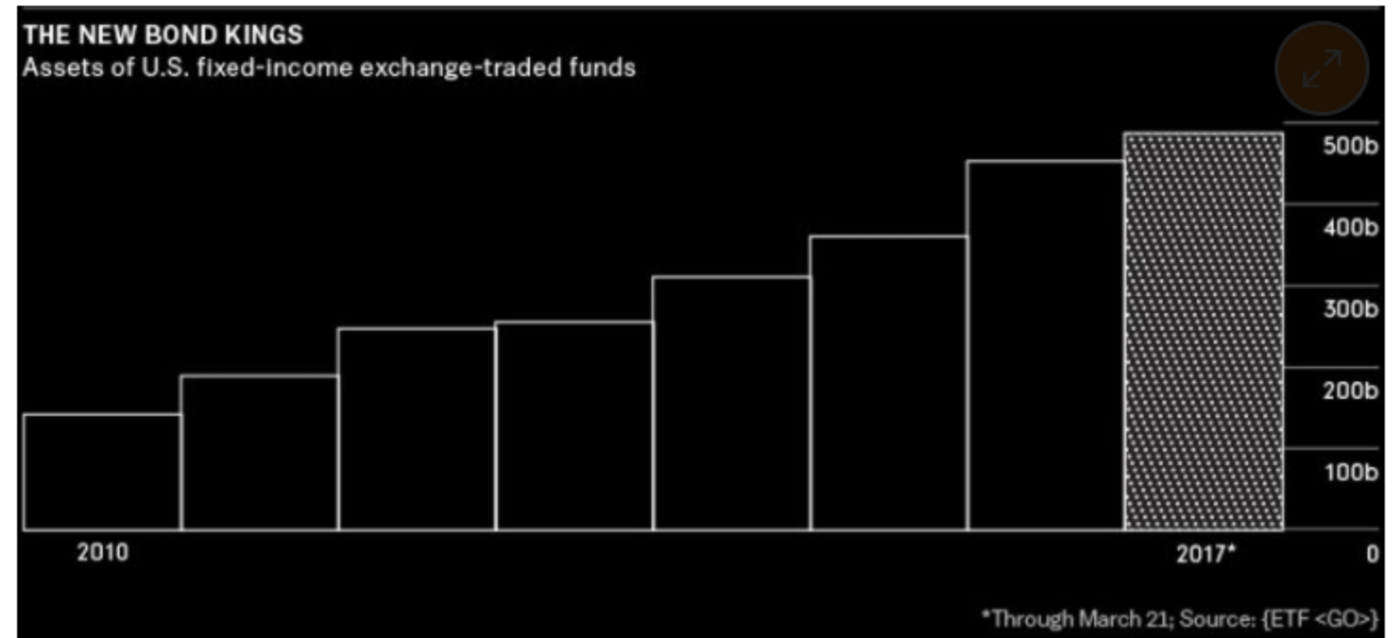

Meanwhile, ETFs are also moving into lots of markets that they don’t obviously seem suited for. Unlike stocks, bonds are not very standardized -- they have different issuers, maturities and contract terms. But more and more bonds are getting bundled together and traded on exchanges, with assets approaching $500 billion.

Many modern ETFs even include derivatives, such as futures, swaps and options.

Given the explosive history of other recent financial innovations, it makes sense to ask whether overuse or misuse of ETFs will also lead to a disaster. Fortunately, many people are already looking for ways that the ETF market might go wrong.

Some of the concerns are more about the long term. A recent study by finance researchers Doron Israeli, Charles Lee and Suhas Sridharan found that being included in an ETF often makes an asset less liquid, and reduces the correlation between its price and its fundamental value. That implies that ETFs make the market more careless -- just as securitization lulled lenders into ignoring the quality of individual mortgages, ETFs might be causing investors to ignore the fundamentals of individual assets. Other academics have focused on the ways passive investing might stifle industry competition.

But that still doesn’t tell us how ETFs might cause a financial crisis. Some asset managers have called the funds “weapons of mass destruction,” but as my Bloomberg View colleague Barry Ritholtz notes, they haven’t yet made a convincing case.

That doesn’t mean there is no such case to be made. My own biggest worry about ETFs revolves around liquidity.

There is no single unified definition of liquidity. In general it means the ease with which you can trade an asset, but that depends on conditions in the market -- mortgage-backed securities were plenty liquid before the crisis struck, but became incredibly illiquid once people started doubting the quality of their ingredients.

ETFs look very liquid, because as the name implies, you can trade them on exchanges. Take a thousand hard-to-trade bonds and pile them into an ETF, and you suddenly have one bond fund that the lowliest retail investor can buy and sell at will.

But what happens in a crisis? Suppose some bonds turn out to be a lot lower-quality than most investors believed. Without ETFs, those bonds would plunge in price, but other bonds would be fine. But now imagine that both the bad bonds and the good bonds are all bundled into ETFs. Now, when the bad bonds are discovered to be bad, investors who ignored the composition of their funds will suddenly wake up to the fact that they might contain toxic assets. Liquidity in the ETF market might suddenly dry up, as everyone tries to figure out which ETFs have lots of junk and which ones don't.

With assets like stocks, this isn’t so much of a danger -- when stocks go bust, everyone can see which ones are bad. But when the ingredients in an ETF are complex, highly heterogeneous assets, as is the case with many bonds and derivatives, one ETF might be fine while another is worthless, and yet investors may ignore the differences until it’s too late.

Another possibility, pointed out to me by a friend in asset management, is that some of the individual securities in an ETF might start to have their own liquidity problems. If banks or other big broker-dealers suddenly become unwilling to facilitate the trading of certain kinds of bonds, ETFs that include large amounts of those particular bonds might suddenly plunge in price. Investors now buying up ETF shares might not realize that danger, thus leading to general overpricing.

So the more bespoke and exotic markets ETFs expand into, the greater the worry that they could be involved in a 2008-style liquidity crunch. That could pose risks for key financial institutions that hold ETFs, and it could also spell danger for individual investors’ retirement savings.

A few people are already worrying about this possibility, which is good. The more we worry about financial innovations in advance, the less chance we’ll need a crisis to teach us the limits of those innovations.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

To contact the author of this story: Noah Smith at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view