By Dani Burger

(Bloomberg) --The smart beta exchange-traded fund you just bought may not have been the wisest idea -- at least according to an upstart quantitative investing shop with ties to the world’s biggest hedge fund.

That’s because the utility of investing exclusively based on factors like momentum, value and low volatility is exaggerated by most providers, according to Maneesh Shanbhag, who co-founded $500 million Greenline Partners LLC after five years at Bridgewater Associates LP. In fact, he says, factors only work as a way to find stocks to bet against.

“There is a tiny bit that is good, but a lot in the space where the benefits are oversold,” said Shanbhag, who runs what he calls “factor inspired” risk parity portfolios. “All of them are better at predicting losers than selecting winners. Yet most products are long only.”

This is a frightening proposition, considering how ETFs that exclusively bet on stocks rising have ballooned in popularity.

The issue comes down whether factors good at picking stocks that are primed to rise. At its core, factor investing targets shares with characteristics shown to beat the market over time. The logic has been applied to countless smart beta ETFs that, say, buy the 100 least volatile stocks in the S&P 500 Index, like the $7 billion PowerShares S&P 500 Low Volatility ETF, symbol SPLV.

In the ETF universe alone, U.S. smart beta funds have grown seven-fold over the past decade, with total assets at a record $612 billion. Yet, according to Shanbhag, this is a lousy way to find the best shares to buy. What factors are good at identifying which stocks are most likely to fall -- something that doesn’t really benefit long-only ETFs. In addition, since smart beta funds focus on just a small slice of the investing world, the funds are less diverse and therefore more volatile.

“What’s promised by some of these ETFs is a certain consistency to their returns,” Shanbhag said. “But if you’re selecting a smaller segment from the universe, you aren’t ginning the benefits from a larger segment that just eliminates the really bad ones.”

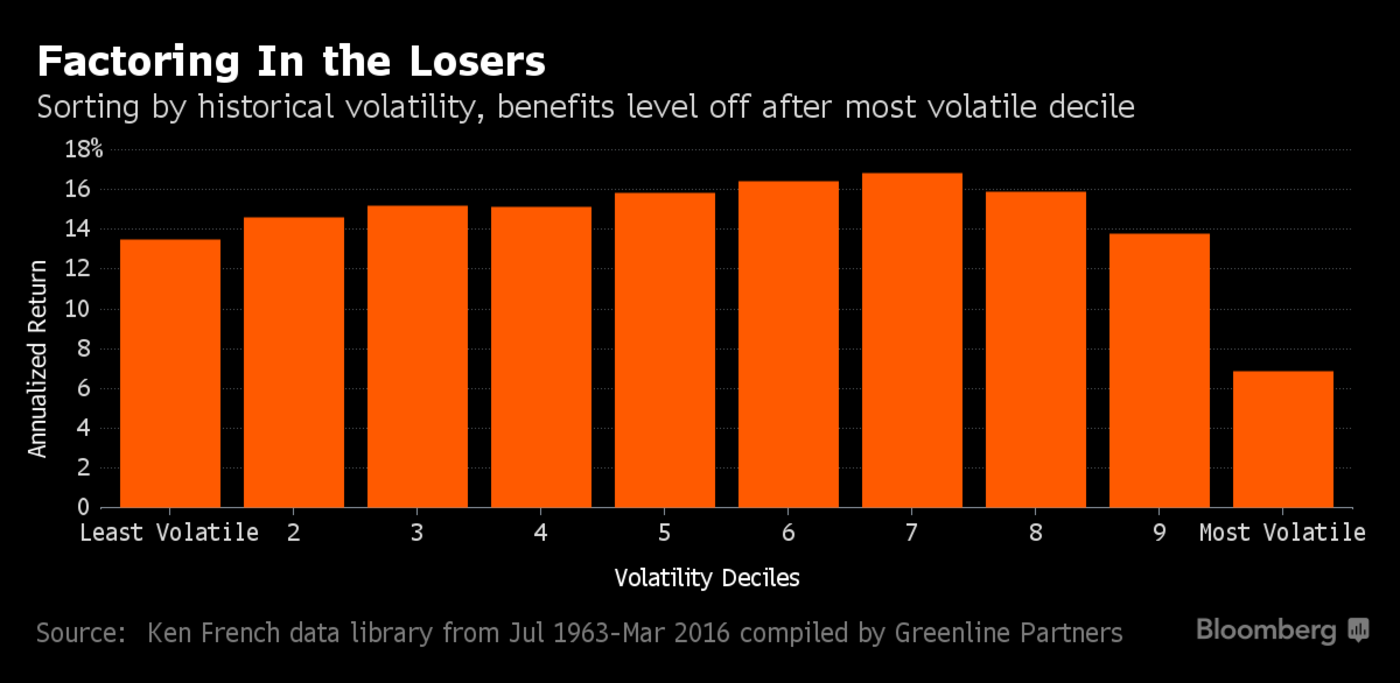

Diminishing Benefits

For example, if you sorted U.S. stocks by volatility over the past half-century, the most volatile group has the worst annualized returns, data analyzed by Greenline found. But after that, the benefits of the low-volatility factor level off, and the other groups’ returns are virtually indistinguishable from each other. In fact, the group with the lowest volatility posted annualized returns of 13 percent, compared with 16 percent for the middle group.

Representatives from PowerShares and iShares provider BlackRock Inc. declined to comment.

Through the close of trading Monday, Powershares’s SPLV had returned 82 percent since it’s inception on May 5, 2011, compared with the S&P 500’s 83 percent return. In research published late last year, Greenline found the same effect over and over. After sorting by factors many quants use -- like momentum, value, quality and size -- the worst segments underperformed, but the others showed little dispersion. Most factors are already priced into the market, especially in U.S. equities, where a large number of informed players are chasing high profits, according to Shanbhag.

Value Exception

“Very few of what’s considered a factor today are unique factors,” he said. “Most of them are largely priced in and can’t help differentiate between the winners and the middle of the pack.”

Shanbhag has been using that philosophy in the equity portion of his risk parity portfolios -- a strategy that weights asset classes based on riskiness. Instead of investing in factors, he uses them as screens to weed out the losers. The New York-based asset manager returned about 13 percent last year, compared with 11.6 percent for Bridgewater’s risk-parity All Weather fund and 9.5 percent for the S&P 500.

Much of Shanbhag’s research into factors is born from skepticism about most factor products. The exception is perhaps value, which appears to be the most robust and helpful for avoiding overpriced securities, he said.

He’s not alone in his view. Some researchers believe that factors like low volatility and quality may just be another version of value, albeit one that’s less effective for investors. Others think that gains in some factors may be due to a completely separate and unsustainable phenomena, like low-vol being overweight in defensive sectors that benefited from falling interest rates, Shanbhag said.

“If you take volatility and quality and agree there’s no premium, you’re playing a game with low odds. With that type of diversification, you’ll never be concentrated in the best,” Shanbhag said. “They’re over-promising and under-delivering.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Dani Burger in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at [email protected] Eric J. Weiner