By Rachel Evans and Carolina Wilson

(Bloomberg) --For exchange-traded funds, finding that all-important first investor is the difference between life and death. Lately, that helping hand is getting harder to come by.

ETFs, investment vehicles that have piled up more than $3 trillion in the U.S. by giving the masses a low-cost and transparent way of tracking an index, once had little difficulty locating money to get off the ground. The tsunami of investor dollars heading into passive products meant that early backers were all but assured to recoup their investment.

But hobbled by regulations and mounting costs, the market makers that used to act as initial investors are increasingly telling issuers to look elsewhere for seed capital. Issuers in turn are having to become more creative to find that first dollop of cash for their funds.

“We have to be thoughtful about how we launch products,” said Nick Cherney, head of exchange-traded products at Janus Henderson Group Plc, which has $323 million across nine funds. “You don’t get the same warm welcome that you used to get.”

Instead of leaning on its lead market maker to seed its Short Duration Income ETF, Janus obtained more than $20 million of startup capital from JPMorgan Chase & Co. That ETF, ticker VNLA, now has $151 million of assets.

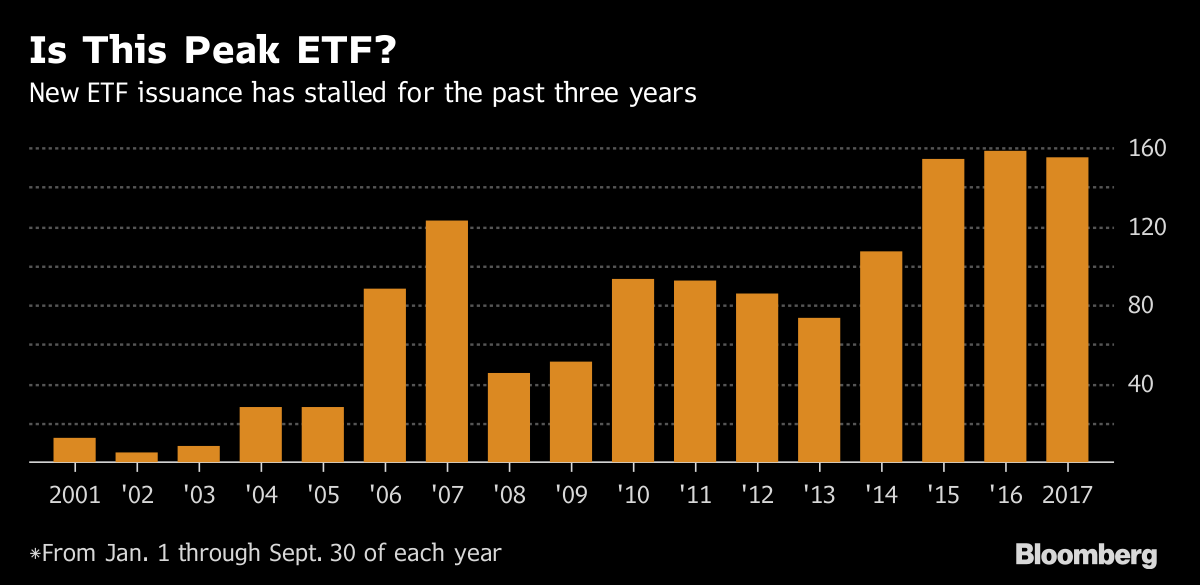

Issuers started around 150 new funds through Sept. 30 this year, roughly the same amount as in the first nine months of 2015 and 2016, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. While cut-throat competition and record low volatility are playing their part in thinning the herd, changes to how issuers obtain seed money may be doing more than either to cull the number of ETFs.

Motley Crew

Seed money matters because before an ETF can be listed on an exchange, it must acquire the securities included in the index it’s tracking, allowing traders to set the price of the fund in line with the value of its underlying assets.

The motley crew of banks, brokers and electronic traders that oversee ETF transactions -- known as lead market makers -- have traditionally provided that capital. After putting up the cash, these firms then settle into their more familiar role: ensuring that the fund trades smoothly by providing the best price at which an investor can buy or sell the ETF.

But making markets for ETFs has become less lucrative. New rules have boosted the amount of capital lenders must set aside to cover these trades, sending banks scurrying. Nimbler firms have stepped into the breach, but the increasing complexity of providing prices for over 2,000 ETFs has rendered market making more complicated and expensive.

As a result, many market makers are telling issuers to look elsewhere for their cash.

“There’s not a whole lot of willing providers,” said Damon Walvoord, co-head of the ETF group at Susquehanna International Group, which is lead market maker for around 350 funds. “More and more, we see the two being done separately. In order to relieve the burden of the ‘seed ask’ of their trading partners, they’re able to find that seed money internally somehow.”

Family Affair

Principal Global Investors LLC, for example, didn’t wander far to find the capital it needed to start some of its 11 ETFs. It tapped its parent, Principal Financial Group Inc., and an affiliate, Edge Asset Management Inc. At least $272 million invested in the firm’s $289 million U.S. Small Cap ETF, symbol PSC, came from affiliated companies as of June 30, according to regulatory filings.

The ETF issuer works with the asset allocating part of the firm to ensure that its funds meet the money manager’s goals, as well as those of external investors, according to Paul Kim, head of ETF strategy at Principal.

IndexIQ, which was acquired by New York Life Investment Management in 2015, benefited from a similar arrangement. The asset manager invested $63 million into the IQ Chaikin U.S. Small Cap ETF in its first month, helping to boost assets to more than $250 million in the span of just five months, regulatory filings show.

“As a purchaser of ETFs, we were able to help design what we would want to own that would help diversify and complete our own portfolios,” Jae Yoon, chief investment officer of New York Life Investment Management, said at an industry conference earlier this year.

Angel’s Share

Other issuers are seeking out so-called angel investors, external asset allocators that are willing to commit capital to new ETFs. Often these investors work with issuers to ensure a fund’s strategy meets a particular need.

State Street Corp., for example, created its SPDR SSGA Gender Diversity Index ETF, ticker SHE, for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System. The fund invests in U.S. companies that actively promote women to boards and senior management roles.

Employees Retirement System of Texas meanwhile worked with Deutsche Bank AG to create the Xtrackers USD High Yield Corporate Bond ETF, investing more than $100 million into the fund.

As that model becomes more common, a drop in the number of new ETFs may be just the start. If the only funds making it into the world are ones with deep-pocketed backers, ETFs could gradually become more vanilla, according to Eric Balchunas, analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. That might disappoint those who look to the products for the ‘out there’ exposures they can’t find anywhere else.

“The imagination is still there, so the spaghetti cannon still exists,” said Balchunas. “But this seed challenge adds a pretty big filter to it.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Rachel Evans in New York at [email protected] ;Carolina Wilson in New York City at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nikolaj Gammeltoft at [email protected] Yakob Peterseil, Eric J. Weiner