Back in April, Bloomberg columnist Jim Bianco decried the decline of active management, claiming many fund runners are being skunked by low-cost and passive exchange traded funds. “Active managers,” says Bianco, “cannot generate enough alpha to justify the higher fees over passive ETFs.”

That may be so, but what about active management within the ETF space? Are active managers more successful in a lower-cost environment? Just how much alpha are they producing anyway? And at what cost to the investor?

To answer these questions, we sorted the actively managed ETF universe for seasoned portfolios focused on U.S. large-cap stocks. For us, “seasoned” means funds with at least a one-year history. It’s a fairly new breed of cat, these alpha-seeking large-cap ETFs.

Before we discuss the results of our study, a clarification is in order. It’s important to make a distinction between an investment’s return and its alpha. An investment return is simple to derive and readily comprehended. Alpha requires four inputs and is derived formulaically. Alpha is comparative; it describes a fund’s excess return over (or under) that of its beta-adjusted benchmark. Beta’s, therefore, a predicate of alpha—the higher an ETF’s beta, the tougher the alpha ask. That said, a portfolio with the highest investment return may not necessarily yield the highest alpha.

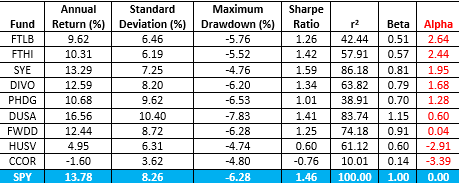

So what did we find? Well, we discovered that the past 12 months has been the year of the option overlay. Three of the top four alpha producers (see Table 1) relied on option plays to augment income or dampen market risk.

Table 1. Alpha-Seeking ETF Performance

Alpha by the Numbers

At the alpha pinnacle is the First Trust Hedged BuyWrite Income ETF (Nasdaq: FTLB), a portfolio of 150 dividend-paying stocks draped with a collar of short calls and long puts on the S&P 500. The strategy works on two levels. First, income is boosted by the receipt of call premium in excess of the put cost. Second, the option collar operates as a functional short S&P 500 position, essentially insulating the manager’s model-driven portfolio from systematic risk. The fund’s highest sector exposure is to consumer cyclicals, technology and energy. With an expense ratio of 85 basis points, FTLB isn’t cheap, but given its high alpha coefficient, it’s very efficient.

FTLB’s stablemate, the First Trust BuyWrite Income ETF (Nasdaq: FTHI) holds the same 150-stock portfolio but foregoes put purchases. Its mandate is high income. Writing out-of-the-money calls on the S&P 500 gooses the fund’s distribution yield higher but potentially limits portfolio gains during market rallies. Without the put protection, FTHI’s beta is a notch higher than FTLB’s, producing a slightly lower alpha coefficient for the same 85 basis points expense.

No options are employed by the SPDR MFS Systematic Core Equity ETF (NYSE Arca: SYE), just old-fashioned bottom-up analysis that looks for undervalued stocks with the potential to produce market-beating results. Over the past 12 months, SYE’s returns mostly kept pace with the S&P 500, but hugged the index with less volatility. Exposure to the technology, healthcare and financial sectors are strongest. With expenses running at a relatively modest 60 basis point rate, SYE is one of the most efficient alpha producers in the field.

Writing covered calls is employed by the Amplify YieldShares CWP Dividend & Option Income ETF (NYSE Arca: DIVO), but unlike that of FTHI, it’s tactical rather than strategic. DIVO’s manager selects about two dozen dividend-paying stocks from various sectors of the S&P 500, then sells calls on those stocks, aiming to produce a gross yield between 4 and 7 percent annually. Buy-writes are functionally equivalent to short puts; they can be profitable so long as the market for the stock doesn’t tank. Upside is limited because the stock can be called away in a rally, making DIVO’s strategy well-suited to a range-bound market with a slightly bullish bias. Financial, industrial and consumer cyclical exposure is highest inside this portfolio. With expenses running rich at 96 basis points, the ETF is a moderately efficient alpha producer.

The cheapskate award goes to the Invesco S&P 500 Downside Hedged Portfolio (NYSE Arca: PHDG), a fund that dynamically allocates its portfolio to S&P 500 stocks, VIX futures and cash for just 39 basis points. While VIX futures can provide powerful protection in severe downturns, the cost of maintaining a position is positively corrosive. Despite this, PHDG capitalized on the market’s recent volatility spike to good effect alphawise.

A bottom-up approach to security analysis is employed by the manager of the Davis Select U.S. Equity ETF (Nasdaq: DUSA). Here, the fund runners focus on quality factors in the hope of finding long-term holds that will ultimately realize their intrinsic value. For 65 basis points you get strong exposure to financials, industrials and consumer cyclicals.

The AdvisorShares Madrona Forward Domestic ETF (NYSE Arca: FWDD) holds equities selected on the basis of their forward-looking P/E ratios. By culling companies with poor profit projections, exposure to financials, consumer cyclicals and industrials are amplified. FWDD’s 125 basis point annual cost makes the portfolio the most expensive ETF in our field.

Volatility forecasts determine the weightings in the First Trust Horizon Managed Volatility Domestic ETF (NYSE Arca: HUSV). The portfolio is comprised of 50 to 70 domestic stocks with the lowest expected standard deviation, yielding outsized exposure to the industrial, financial and utilities sectors.

While option overlays were used to good effect with other funds in the table, the derivative strategy was mostly a bust for the Cambria Core Equity ETF (NYSE Arca: CCOR). Starting with a portfolio of high-quality, dividend-paying stocks, CCOR’s manager, like the FTLB fund runner, layers on an index option collar—long puts and short calls—hedging the fund, to some degree, from market downdrafts. Unfortunately, the CCOR model, undermined in great part by its 105 basis point cost, fails as an alpha winner. At last look, technology, industrial and financial stocks dominated the fund’s sector exposure.

The Cost of Active Management

The alpha coefficient is a metric that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of portfolio management in outdoing the market, but it presents a conundrum. Like it or not, part of a fund’s performance reflected in its alpha can be attributed to the market itself. To gauge the true effectiveness of an active strategy, we have to isolate that part of the portfolio that’s actually idiosyncratic.

The degree to which an investment’s return can be explained by its benchmark—the market—is reflected in its r-squared (r2) coefficient. Using a technique advanced by the late SUNY-Albany professor Ross Miller, an r2 value can be mathematically manipulated to derive a portfolio’s active weight and, with further distillation, the alpha directly attributable to that segment.

As you can see in Table 2, there can be a significant variance between a portfolio’s traditional alpha and the alpha ascribed solely to its active weight. Look at the SYE Systematic Core portfolio as an example. It earned a not-too-shabby 1.95 traditional alpha coefficient but only warranted third place in Table 1. By limiting the alpha analysis to SYE’s active portion, however, the portfolio handily takes first place with a 6.82 coefficient. Only by dint of its higher expense ratio did SYE end up with a slightly lower alpha cost efficiency than the Invesco PHDG fund.

Table 2. ETF Alpha Efficiency

While SYE was most successful in leveraging its alpha efficiency, the difference between the traditional and active alpha values for the Davis DUSA portfolio is also remarkable. All the more notable is DUSA’s and SYE’s relatively small active weights. Pound-for-pound, the managers of these two funds are making the most of their small active cut-outs.

So, what do we know as the result of this exercise? Just this: Among seasoned ETFs, there’s alpha to be snagged. Most alpha-seeking portfolios, in fact, cranked out positive risk-adjusted returns over the past 12 months. There’s substantial variance, naturally, in the quality of those returns.

These results are, of course, backward looking. Whether they’re predictive of future outcomes, only time will tell. What we can say is that the active managers panned by Jim Bianco may want to peek at the playbooks used by some of the ETF managers at the top of our table.