By Justin Fox

(Bloomberg View) --In 1889, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie offered up a rousing and still-famous defense of the estate tax:

Of all forms of taxation, this seems the wisest. Men who continue hoarding great sums all their lives, the proper use of which for public ends would work good to the community, should be made to feel that the community, in the form of the state, cannot thus be deprived of its proper share. By taxing estates heavily at death the state marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire's unworthy life.

It's still possible to find very rich people espousing similar views. Third-richest-person-in-the-world Warren Buffett was espousing them on television just Tuesday morning. But with yet another Republican administration proposing yet another repeal of the tax (the last repeal was enacted in 2001, took full effect in 2010 and expired in 2011), and public sentiment seemingly in favor of such a move, it's worth considering just what has happened to change people's minds since 1889.

When Carnegie made his argument, he had the political wind at his back. Over the next 15 years, 24 states (out of 45) enacted broad inheritance taxes, and the Republican-dominated federal government temporarily used a 15 percent estate levy (it was enacted in 1898 and repealed in 1902) to finance the Spanish-American War and other military adventures. At least part of the political support for the estate tax in those days may have stemmed from a desire to stave off a federal income tax, University of California at Santa Barbara historian W. Elliot Brownlee writes in his "Federal Taxation in America: A Short History." But it's striking to see the words that a Republican president, Theodore Roosevelt, wielded in support of both estate and income taxes in 1906:

The man of great wealth owes a peculiar obligation to the State, because he derives special advantages from the mere existence of government.

The estate tax finally came to stay in 1916, after the Democratic Woodrow Wilson administration had already succeeded (in 1913) in getting a federal income tax approved. With American intervention in World War I looming, Wilson wanted money for big-time increases in military spending, and adding an estate tax was actually less controversial than expanding the income tax. And so it remained for many, many decades.

Then ... something changed. In a fascinating 2003 paper, political scientists Mayling Birney and Ian Shapiro date the beginning of the anti-estate-tax movement to a 1992 bill sponsored by prominent House Democrats Richard Gephardt and Henry Waxman that would have increased the number of families facing the tax. That brought a "strong and entirely unexpected backlash," initially led by an estate planner from Orange County, California, that within a few years had developed into a repeal movement with bipartisan backing. Public opinion turned out, when pollsters first started asking about the issue in the late 1990s, to lean against the estate tax, with poll respondents continuing to view it negatively even when informed that it affected at most the wealthiest 2 percent of the population. It was not a high priority for most voters, and when pollsters asked about estate tax reform versus repeal, most respondents favored the former. But in a time of budget surpluses (remember those?), a dedicated core of repeal proponents was able to convince majorities in the House and Senate in 2000 to do away with the tax and, after President Bill Clinton vetoed the bill, do so again in 2001 as part of a larger package of tax cuts signed into law by President George W. Bush.

Those tax cuts came with an expiration date, though, because backers didn't have the 60 votes required by the 1990 "Byrd rule" for legislation that increases deficits past a 10-year window. When the 10 years ended, with budget surpluses a distant memory and a Democrat in the White House, the repeal was allowed to expire -- although the size of estates exempted from the tax was increased and indexed to inflation, and now stands at $5.49 million, with a top rate of 40 percent.

Now, the Donald Trump administration and Republican congressional leaders want to give repeal another go. This stance continues to find support in polls: An Ipsos survey conducted earlier this year for National Public Radio found that 65 percent of respondents favored repeal of the estate tax, and 76 percent favored repeal of the "death tax" (a favorite term of estate tax opponents). There's no budget surplus this time to cushion the blow of losing the tax -- although of the $2.4 trillion that the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center estimates that the proposed Republican tax cuts would cost over 10 years, the estate tax accounts for just $239 billion.

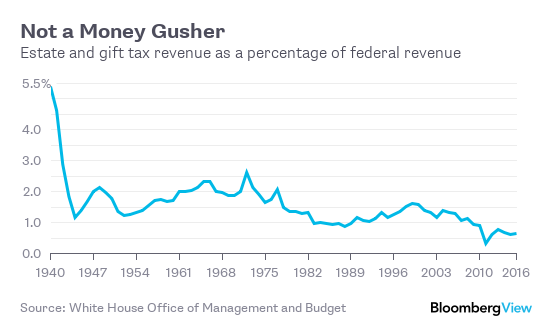

The best argument against the estate tax, really, seems to be that it brings economic distortion (as the wealthy go to great lengths to circumvent it) and family pain without delivering a whole lot of money to the federal government. The tax's importance to overall government finance has certainly declined over the decades:

Still, it's a tax that doesn't affect many Americans, with the Tax Policy Center estimating that only 5,460 estates will owe taxes in 2017. It would, however, certainly affect the family of the president -- in a back-of-the-envelope calculation last week, the New York Times figured that estate tax repeal would save Trump's heirs $1.1 billion. Which for me inevitably brings to mind the arguments of the late 1800s. Here's the great University of Wisconsin economist Richard T. Ely, co-founder of the American Economic Association, assessing the merits of an estate tax in 1888:

One of the principles which controlled the action of Jefferson and other founders of the republic, was the abolition of hereditary distinctions and privileges, and their aim was to force each one to rely on his own exertions for his own fortune, desiring to give to all as nearly as practicable an equal start in the race of life.

It has been urged by others that one of the most dangerous tendencies of our times is the increasing aggregation of wealth in a few hands. This scheme is a slight corrective, which is in harmony with the spirit of our institutions.

Is that really a tradition we want to turn our backs on?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

To contact the author of this story: Justin Fox at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view