When counseling clients who wish to ensure that their estate plan or wealth management structure complies with Sharia law, a wealth planner or financial advisor should pay particular attention to certain key aspects of that law. For example, Sharia law may limit the range of permissible investments that a client may wish to invest in. At the same time, the principles of Sharia succession (which may vary depending upon the school of Islam followed by the client), may significantly affect the possibility of implementing standard estate planning or wealth management structures.

While a wealth planner or financial advisor who’s not based in the Middle East may not be expected to master the subtleties of Sharia succession and property law, an awareness of its key features is an essential tool in an international estate planner’s toolbox and may present planning opportunities for a segment of high net worth individuals that may be unaware of the use of trusts as a flexible succession planning option.

There are a number of important legal considerations that wealth planners and financial advisors should keep in mind when counseling clients who abide by Sharia law, particularly with respect to the use of trusts.

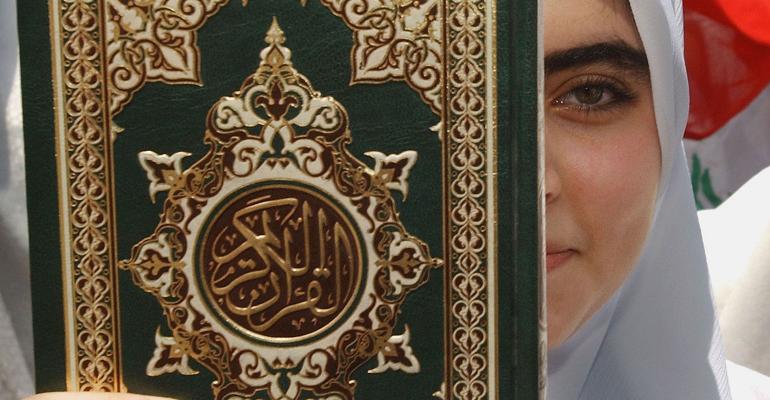

Quranic Law

First and foremost, the law of succession, family relations and property are usually heavily dependent on mandatory rules derived from Quranic law. Very generally, the sources of Quranic law include the Quran, the book of Islamic holy scripture believed by Muslims to be the words of Allah verbatim as revealed to his prophet Muhammad in the seventh century, and the Sunnah, which are rules from the prophet’s sayings (Hadiths) and actions.

As an example, the inheritance of a Muslim is administered in accordance with the principles of Sharia law, according to which (generally) each son is entitled to twice the share of a daughter, and a wife is entitled to one-eighth of the property of her husband, if the deceased husband died leaving children. A surviving husband’s Sharia inheritance will generally be double a surviving wife’s; namely, a surviving husband will receive one-quarter of the estate if the deceased spouse had children, while if the wife has no children, the husband is entitled to one-half of the estate. The foregoing is subject to variation depending on the circumstances. Furthermore, the denomination of Islam practiced by the decedent may also impact how his heirs inherit from his estate. For Sunni Muslims, a female only child is entitled to one-half of the estate, while multiple daughters in the absence of any sons are entitled to two-thirds of the estate. Paternal uncles, if any, would be eligible to inherit the other half of the estate if there’s a female only child. On the other hand, an only daughter of a Shia decedent may inherit absolutely. For both Sunni and Shia Muslims, if the husband has no children, his wife is entitled to one-fourth of the estate.

Sharia law sources provide for a complex set of additional fractional distributions of the deceased’s estate depending on which of his relatives are then living. The deceased is also entitled to freely dispose of up to one-third of his estate to non-Quranic heirs by will. Generally, unlike the civil law system, that one-third can’t be used to prefer one particular individual heir at the expense of other heirs specified under Sharia law.

Lifetime gifts aren’t subject to the Quranic rules of inheritance and may be made freely by an individual. However, if the gift was made during “sickness of death,” it may be clawed back into the decedent’s estate. Sickness of death refers to that sickness that led to one’s death.

Limited Exposure to Trusts

Second, Middle Eastern countries have generally had limited exposure to the trust as a wealth planning tool. While certain countries have introduced domestic trust provisions — the Dubai International Financial Centre Trust Law DIFC Law No. 11 of 2005 or the Bahrain Financial Trust Law of 2006 — these haven’t been fully tested by the respective tax and administrative authorities. Therefore, these trust regimes lack clarity in how they may be properly used for efficient tax planning purposes. Also, it’s useful to note that no Middle Eastern country has signed or ratified the Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition. Israel, on the other hand, has a well-established trust law based on the English common law system that permits trusts to be settled with or without Israeli resident beneficiaries. As with all other Middle Eastern jurisdictions, Israel isn’t a signatory to the Hague Convention of 1985.

An Appealing Solution?

In principle, trusts may be perceived as an appealing solution to meet the goals of clients from the Middle East.

For example, Muslims living in Western nations may use trusts to distribute their assets in accordance with the principles of Sharia law. This can be immensely useful for individuals who own property in Europe or North America to ensure that their estate planning goals are achieved. Common law and civil law inheritance rules may be quite different from those of the Sharia.

Properly structured common law trusts can protect a family’s assets from future creditors and political instability. Because the trustee will be the legal owner of the trust property, a potential creditor of the settlor will have to prove that the purpose of the trust was to hinder, delay or avoid creditors. Trusts settled by solvent individuals usually have acceptable purposes, such as providing future resources for family members. Properly structured trusts settled by parents are almost always immune from attacks by creditors of their children or grandchildren.

Revolutions or invasions may result in attempts to nationalize or confiscate property owned by nationals. Foreign trustees will rarely be personally subject to such political asset blocking orders, and if the settlor legitimately acquired the assets donated to the trust, the trustee may not be subject to asset-blocking, either in the trustee’s own jurisdiction, or in the jurisdiction where the trust fund is deposited. International diversification of a family’s legitimately acquired assets is always the first step in any plan to minimize political risk.

Trusts may also be structured so that they’re Sharia-compliant by requiring that the trustee avoid investments that are prohibited under the Quran. These include, but aren’t limited to, conventional financial services that feature transactions based on interest or speculation, certain food and beverage industry sectors (e.g., businesses that generate revenue from pork or alcoholic products), the tobacco industry, activity related to illegal drugs, gambling and certain sectors of the entertainment industry (e.g., adult entertainment).

Alternatively, Muslims living in jurisdictions subject to Sharia law may use trusts to plan for bequests that don’t follow the Quranic rules of succession. For instance, if an individual would like to provide his sons and daughters with equal shares of his estate, a trust may be used as a tool to achieve this goal. Trusts may also be used to provide an inheritance to non-Muslim family members, illegitimate children or more distant relatives such as grandchildren, who would otherwise be disinherited if the estate is governed by Sharia law.

Traps for the Unwary

The use of trusts in the Middle East, however, presents a number of potential traps for the unwary.

First, a Sharia-compliant trust may need to be reviewed by an Islamic scholar in the settlor’s home jurisdiction to ensure that it’s compliant from a Sharia law perspective. This is an additional layer of cost and complexity that may arise depending on the client’s desire for a Sharia-compliant trust and his residence.

Second, properly established trusts are created through inter vivos gifts (hiba). Similar to the conditions of successful inter vivos gift giving in the United States, often, the settlor must show his intention to make the gift while the trustees must show their acceptance of the gift. Lifetime gifts aren’t subject to Sharia after-death mandatory distributions unless the gift was made during “sickness of death.” This may raise difficulties when the trust also needs to qualify under specific requirements of a foreign jurisdiction’s tax laws. For example, for U.S. tax purposes, a foreign trust with U.S. beneficiaries is frequently structured to qualify as a foreign grantor trust under Internal Revenue Code Section 672(f)(2).1 To qualify as a foreign grantor trust, (1) the grantor must retain the power to revest absolutely in the grantor title to the trust property in himself, or (2) the trust deed must provide that the only amounts distributable from the trust (whether income or corpus) during the lifetime of the grantor are amounts distributable to the grantor or the grantor’s spouse. Depending on the terms of the trust deed, it may be possible to draft a trust that qualifies as a foreign grantor trust for U.S. tax purposes and is treated as a completed gift of the grantor for Sharia law purposes.

Third, depending on the jurisdiction, not all Middle Eastern countries will recognize the separation of legal and beneficial ownership of assets, in which case the use of a foreign trust may lead to unwarranted consequences. This usually isn’t a problem with a foreign law trust holding geographically diversified investments, but careful consultation with local counsel is necessary to ensure that this situation does not arise.

Endnote

1 This is usually done to avoid the accumulation distribution rules that may otherwise adversely impact the distributions received by a U.S. beneficiary of a foreign non-grantor trust.