By Alessandro Speciale

(Bloomberg) --The Trump trade isn’t an anomaly when you look at previous market rallies after populist politicians took power, according to research at the University of Bonn.

Moritz Schularick, an economics professor at the German institution, told a conference in Frankfurt on Tuesday that his study of 27 comparable episodes in the past century shows that stocks, and to a lesser extent, bonds, tend to benefit. His research encompasses the political ascension of Juan Peron in 1940s Argentina to the three victories of Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi, to the election of current U.S. President Donald Trump.

“There is surprising little evidence that populists are bad for markets,” Schularick told the event organized by the European Association for Banking and Financial History, and Allianz Global Investors. “The contrary seems often to be the case.”

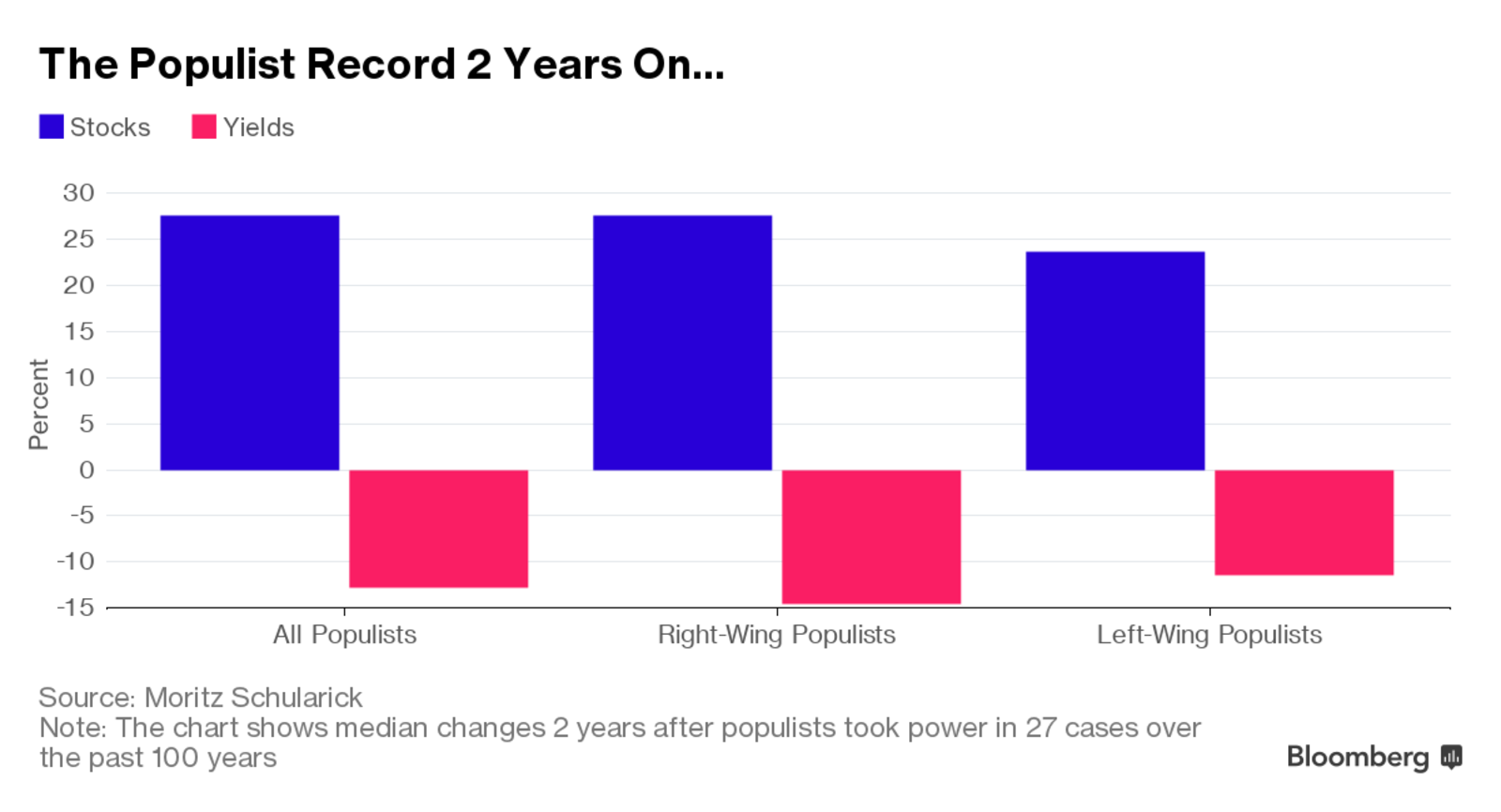

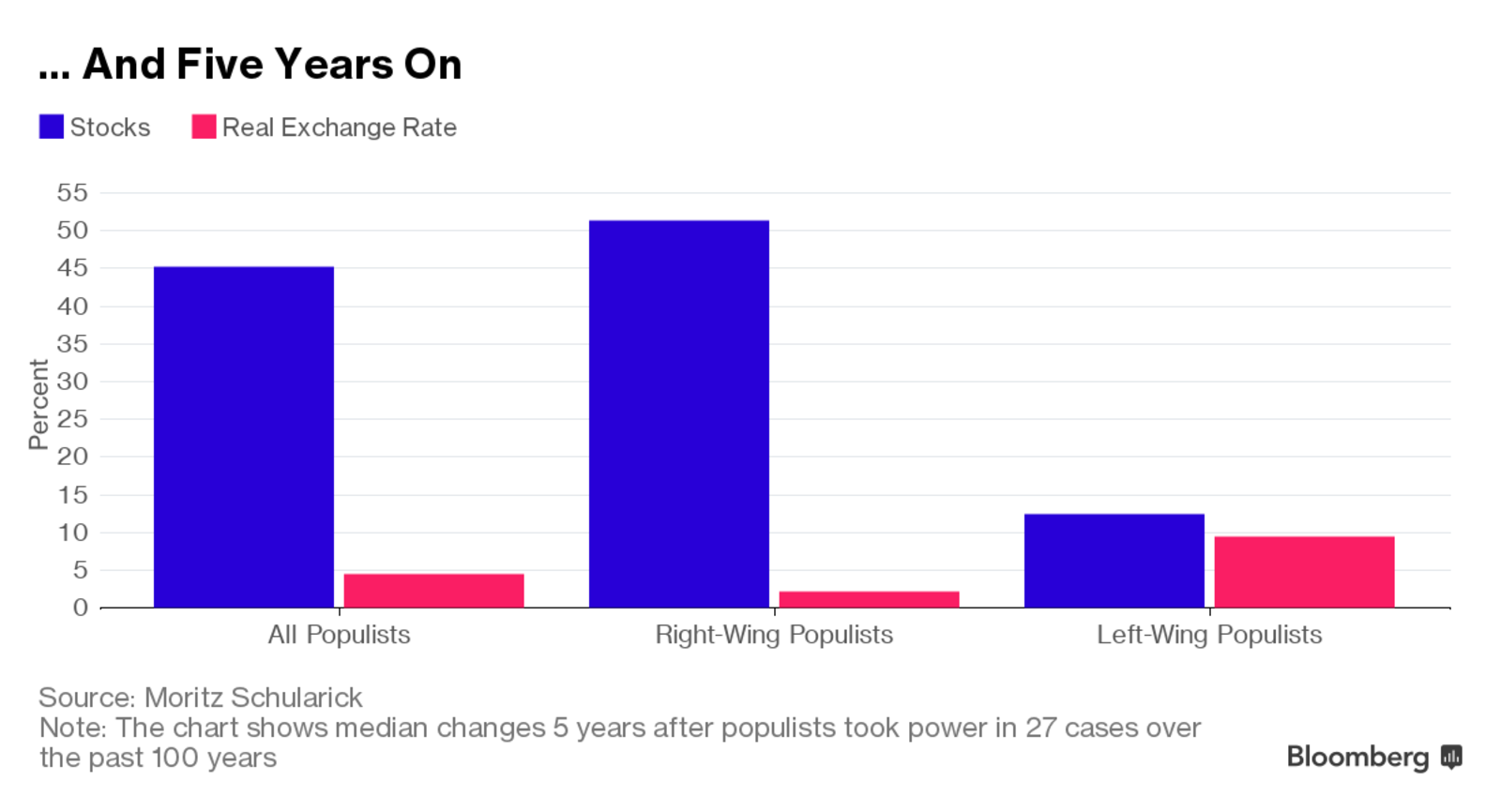

Schularick defines populists as charismatic, confrontational politicians who claim to speak for “the people” against the elites, often pursuing protectionist and nationalist policies. His study shows that bond yields fell a median of 12.7 percent 2 years after such individuals took power. Five years later, stocks gained a median of 45 percent, while sovereign ratings usually improved and currencies appreciated.

His results don’t change dramatically whether the anti-establishment leader came from the left or from the right.

“Markets seem to like right-wing populists a bit more,” Schularick said. “But left-wing populists are not a red flag for markets.”

Contrary to some populists’ own rhetoric before rising to power, what is good for the markets doesn’t prove to be necessarily bad for the people either, he says. His study shows that after five years of populist government, gross domestic product rises a median 1.8 percent, and both investment and spending are up as a proportion of the economy.

These findings go against the received wisdom of economists, identified by Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards in their 1991 essay on “The Macroeconomics of Populism:” “Populist policies do ultimately fail; and when they fail it is always at a frightening cost to the very groups that were supposed to be favored.”

Schularick suggests some reasons for the unlikely success of populist policies: anti-establishment insurgents usually come to power after a crisis, and thus enjoy the fruits from an overdue upswing; protectionism, competitive devaluations and public spending often prove a boon for national companies, boosting the local stock market; and some of their policies, like public investment in a downturn, just work.

Still, some aspects of populists’ success are much more sinister. Those on the right of the political spectrum offer convenient scapegoats in times when anger against elites may otherwise have led to redistribution of capital -- and business confidence rises as a consequence, Schularick says.

“Markets often embrace what, from a citizenship perspective, is dangerous,” he said. “But mainstream politicians may want to take a second look at populist policies as far as investment and public spending is concerned.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Alessandro Speciale in Frankfurt at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at [email protected] Craig Stirling, Zoe Schneeweiss