In the week that just passed, the drama of economic data had its intermission with the data frontage subdued and most of it decidedly second tier in nature. The focus of the interest-rate community shifted to somewhat softer (though potentially far more critical) inputs on the political front and as a result found new impetus to sustain technical gains that were otherwise already underway.

Of course I refer to the fact that the Republican health care bill was pulled from the house vote late Friday, with Trump now threatening to leave the ACA in place and move on. The "moving on" bit is about tax cuts, mostly, and presumably fiscal stimulus. The friction in Washington over all of this is tempting to extrapolate Trump’s broader economic plans in that these too may stumble, or at least retreat from the levels initially offered. Surely, the Freedom Caucus’ balking at the broader GOP effort on health care can translate to balking at a deficit expanding tax cut if unaccompanied by at least equal cuts in spending.

This is not rocket science, by the way. The hope and hype that came in the first few weeks after the election didn’t seem to meet the ready cynicism about campaign promises not translating to active policy. This is another way of saying that the equity rally that started after the election, until this most recent week, was coming on the same vague concepts, and is why this strategist has been rather skeptical. Now as political gaming comes into play, the hype faces challenges. This quite naturally has contributed to a somewhat moribund Treasury rally following what was perhaps the most discounted Fed hike in my 30-year career. In any event, the Treasury market was poised for a technical rally which may have a little bit further to go — think tactical, not strategic — and the S&P 500 poised for a correction.

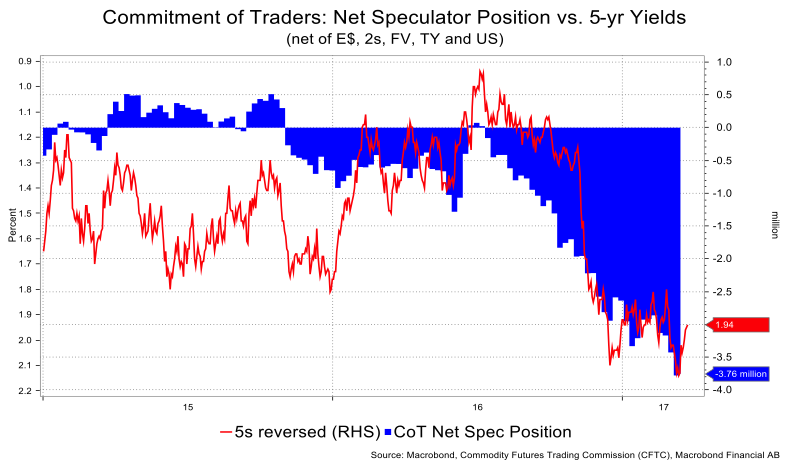

At the risk of sounding (or being made) redundant, I am keen to say that I don’t see a major Treasury rally underway, but I’m open to a challenge. As the above chart shows, the net speculator position in Treasury-related futures is very short (indeed it’s a record short) and DSIs remain in oversold territory. The daily technical charts have worked off a good deal of their bullish impetus, but the weekly have not. I would like more fundamental support for the notion of a bigger rally and wonder if events in Washington with negative repercussions for equity prices could be that.

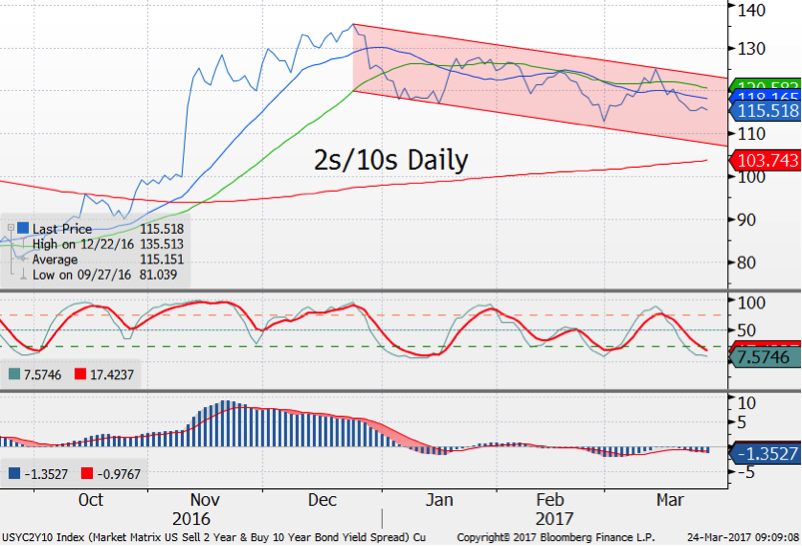

In any event, I see some chance for 10-year yields to creep up towards the 21- and 40-day moving averages, at 2.48 percent and 2.46 percent respectively, and have near resistance at about 2.32 percent (channel bottom) with a short at just over 2.26 percent or the post-election yield low. I’m pretty neutral on the curve though with supply ahead; I am inclined to favor some flattening of 2 and 5 years versus 10 and 30 years.

I’m not sure how interesting this is, but we’ve had a plethora of Fed speakers including Dudley, Evans, George, Harker, Kapan, Kashkari, Mester, Rosengren and Yellen. The amalgamation of all that didn’t reveal too much other than to reiterate generic expectations for more hikes though no great sense of urgency that things are getting out of hand. The end result was a slight dip in Fed Funds expectations for hikes with emphasis on slight. January 2018 Fed Funds slipped from 1.29+ percent at the start of the week to about 1.28+ percent at the end, and December 2017 Fed Funds came in to 1.24 percent from 1.25+ percent. (Note that Fed Fund Futures point to market expectations for the average Funds rate for the given month.)

No big deal, right? Well, in the spirit of splitting hairs, making mountains out of molehills and overusing metaphors, those market levels imply a rather tame trajectory for hikes this year. With a central target now at 87.5 basis points for Fed Funds, getting to 1.27 percent in January implies no more than two hikes and even a bit less than that. Isn’t that interesting? Although the FOMC (Fed Open Mouth Committee) seems quite steady on hikes, the market isn’t buying it. Perhaps the fate of the new health care legislation will serve to temper the risk-on enthusiasm. This doesn’t make me very bullish by any means, but it does serve as temptation to envision limited backups in yields — I’m sticking with 10s being attractive at 2.75-3 percent in a strategic sense.

In addition, here are predictions from the Fed speakers that I picked at random.

Harker, voter: Economic confidence has to translate into action.

Evans, voter: Still unclear about fiscal policy; wage growth less than expected; supports two or three rate hikes this year; uncertainties still pretty high; lower capital expansion may reflect lower trend growth; labor markets strong.

Mester, not a voter: Not going to aggressively shrink balance sheet; normal interest rate lower than before; no strong evidence firms are acting on rising sentiment; built a bit more than three hikes into rate forecast.

George, not a voter: Smaller balance sheet won’t happen quickly.

Rosengren, not a voter: Commercial real estate may become a source of instability.

Williams, not a voter: Sees three or more rate increases this year; start bring balance to more normal levels at end of year; new normal for Funds is 2.5-3 percent.

Let me take some advantage of these snips to reinforce notions I’ve been offering up or, to put it another way, demonstrate that great minds think alike.

Harker talks about needing to see confidence translate into action. This is important recognition given the fact that the Fed hiked in a quarter with 1.9 percent GDP growth (Q4) and did so in a quarter when most forecasts expect another 1 percent handle on GDP (the Bloomberg consensus is at 1.9 percent).

Evans talks about lower capital expansion reflecting lower trend growth. Hmm. So the slow pace of business investment is a structural thing which, in turn, would hint at slower productivity gains. The distinct negative side is that if trend growth is slower, then inflation could come at a lower level of economic expansion and prove problematic for monetary and fiscal policy.

Mester talks about limited evidence that firms are building on confidence; so this is something to watch as we have at least two Fed officials noticing. Presumably sentiment can give way quickly if the "goods" are not delivered. Mester also talks about an unaggressive approach to balance sheet management which lacks details but at least tells you the Fed is cognizant of the risks.

Rosengren spoke about concerns with commercial real estate last summer in the context of monetary policy, something that Fischer spoke about as well. The point I like is that overvalued assets, like commercial real estate, could play into a more aggressive monetary policy if the Fed fears a bubble is forming. Note that Yellen in May 2015 said, “I would highlight that equity-market valuations at this point generally are quite high.” If my total return analysis is correct, the S&P 500 is up 17 percent since then, assuming dividends reinvested.

I inadvertently sent out the chart above last week WITHOUT the requisite update. Those represent the latest preliminary view on inflation from folks in the University of Michigan poll with the five- to 10-year view back at the absolute lows of 2.2 percent. The one-year outlook dipped to 2.4 percent, but it’s been lower. The overlay is with gas prices to give you a sense that prices at the pump do impact inflation expectations.

The relationship has broken down a lot in recent years which is another way of saying that the long-term view of inflation is far less related to gas prices than it once was. Take a view from the 40,000 altitude below, you’ll see a chart of something called Energy Intensity, or the consumption of oil and gas for each dollar of GDP. Note that it’s fallen sharply since the 1970s meaning that energy prices have less of an impact on GDP than they once did. Why? Well a variety of reasons come into play from more fuel efficiency in autos and general usage, to the biggest which is the move from being a manufacturing economy to a service economy. With that and the fact the U.S. is more of an energy producer, the takeaway is that lower energy prices are less a boon to the consumer and more of a drag (negative) for GDP.

Moving ahead, it was another week for some slowing in lending. The Year-over-year weekly figures for commercial and industrial loans show this quite clearly. If you were to take those figures on a quarterly annualized basis, the gain would be negative. This same slowing can be seen on a broader scale too, with a view of loans and leases in overall bank credit.

Why is this going on? It makes some sense that things were slow into the election due to uncertainty, but one would think that revived animal spirits would have been encouraged to borrow (or lend) more aggressively in recent weeks. So here, too, I find a disconnect between sentiment and action. In a conversation with someone who didn’t know what they were talking about (my neighbor), he suggested that this slowed because businesses are planning to bring back all overseas profits; thus, they don’t need the money. But to that argument you need to understand that 1) there are very few companies that hold the vast bulk of those assets and 2) those are large tech and pharmaceutical names that probably wouldn’t have tapped this form of bank credit. In short, this gun doesn’t smoke — and enough metaphors for this week.

The same softening can be seen in consumer-oriented lending (i.e., credit cards, residential real estate and consumer overall).

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence. For further information, please see: https://financialintelligence.informa.com/