(Bloomberg Opinion) -- During the 1920s, the city of Manhattan Beach, California, used the power of eminent domain to seize the only seafront resort in Southern California that welcomed Black beachgoers. The owners received a small fraction of the market value, and together with other Black property owners were essentially run out of town. In a ceremony last week, the deed to the land known as Bruce's Beach was finally restored to the family. What happened in between is a tale not only of racism and theft, but also of the risks that arise when government can act without scrutiny.

Bruce’s Beach was established in 1912 in Manhattan Beach; a decade and a half later, the city took the land by claiming they planned to develop it into a park. But the vaguer the limits on government power, the easier it is to wield that power for a malign purpose. And the limits of eminent domain are vague indeed.

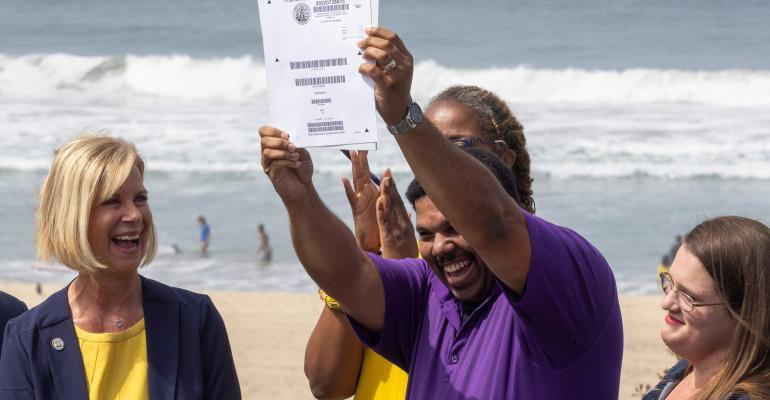

That the city had no interest in building a park quickly became clear. Nothing was done with the property until 1927, when the buildings were torn down. Then the land sat until the 1940s, when it was deeded to the state of California, which eventually returned it to Los Angeles County. Last year, the county agreed to return the property to the Bruces’ heirs, which -- with the dismissal of lawsuits challenging the transfer -- has now been accomplished.

None of this might have been necessary had the courts more closely scrutinized the condemnation proceedings in the first place. But judges didn’t do that back then and they don’t do it now. All that’s necessary is a public purpose that the court doesn’t consider a pretext.

But proving pretext is nearly impossible.

Examples abound of eminent domain takings said to be racially motivated. The historian N.D.B. Connolly tells us how in 1947 the Miami City Commission “took all of twelve hours ... to turn a fifty-year-old community of black homeowners into condemned land for a ‘whites only’ park, school, and fire station.” Or consider the case of East Arlington, Virginia, a thriving Black locality founded by fugitive slaves. During World War II the entire neighborhood was taken by eminent domain to build ... well, the Pentagon.

I’m aware that there’s considerable debate over whether the data show that eminent domain power is disproportionately exercised to the detriment of racial minorities, and I admit that I’ve long been in the camp that prefers to build policy on hard numbers rather than excitement and anecdotes. But in the particular case of eminent domain, the relative laxity of judicial scrutiny creates a space where subterfuge can easily hide.

As happened, for example, in the case of Bruce’s Beach, where the record is crystal clear.

News accounts insist the history has been recently discovered, but the theft of Bruce’s Beach has fascinated historians at least since the 1950s. In 1912, not long after Charles and Willa Bruce purchased the land, the Los Angeles Times reported that “[t]he establishment of a small summer resort for negroes” had “created great agitation among the white property owners of adjoining land.” Neighbors erected “no trespassing” signs across a convenient path from the resort to the water. The Times warned ominously: “Property owners of the Caucasian race who have property surrounding the new resort deplore the state of affairs, but will try to find a remedy, if the negroes try to stay.”

To which Mrs. Bruce replied: “I own this land and I am going to keep it.”

Encouraged by her example, other Black families began to buy land in Manhattan Beach and build summer houses. For over a decade, Black vacationers from as far away as Washington, D.C., and Honolulu flocked to the resort. But what the Black community considered a seaside frolic White residents saw as an “invasion.”

The city began condemnation proceedings on the Bruces’ property in 1924. The family hired lawyers and vowed to fight. As the litigation unfolded, there were multiple “mysterious fires” on the property of Black residents of Manhattan Beach. After the 1926 arson of a much fancier Black resort under construction in Huntington Beach, the Bruces surrendered.

Which brings us back to eminent domain. Although judges are free to consider history when deciding whether a condemnation is pretextual, recent cases make clear that tales of longstanding oppression will play at best a minor role in the judicial calculus. In 2013, a federal court in Illinois ruled that evidence of past mistreatment of Black residents was relevant only if those challenging eminent domain could show that what was happening to their community today “was motivated by the same discriminatory intent.” Just last year a federal court in Texas reached more or less the same conclusion.

Perhaps such results are inevitable, given the state of eminent domain law. And maybe race played no role in these and many other recent condemnations.

The trouble is that even when race is involved, the relatively low bar that the government must surmount in an eminent domain case makes subterfuge relatively easy. Indeed, even under today’s standards, it’s hard to see how Charles and Willa Bruce could have demonstrated in court that Manhattan Beach acted with anything but the purest of intentions.

It’s true that nearby White property owners had sworn to get rid of their resort, but that was a decade earlier. It’s true that many of those same White owners allowed White but not Black strangers onto their own beaches, but the city had no racial prohibitions at the time. (Those came later.) It’s true, as the Bruces’ lawyer pointed out, that Manhattan Beach could instead have condemned any number of nearby White-owned parcels, but the law of eminent domain does not require the government to show that there exists no less restrictive alternative.

The city, for its part, could have pointed to the fact that many other Southern California municipalities that were, around the same time, busily condemning waterfront property to create municipal parks. (Or in a couple of cases, oil terminals.)

Truth be told, under the current law of eminent domain, I doubt that the Bruces would have stood a chance.

And that’s a problem. If it takes a century to right so great a racial injustice, there’s something wrong with the law. Over the past 15 years, all but a handful of states have restricted the use of eminent domain for economic development. But those reforms wouldn’t have helped the Bruces; their land was condemned for a park.

Somehow we have to make taking private property harder. There have been lots of proposals for reform: Necessity. Least-restrictive alternative. I don’t know which adjustment would be best. All I can say for sure is that today’s hands-off attitude toward eminent domain wouldn’t have done a thing to stop the racist theft of Bruce’s Beach.

To contact the author of this story:

Stephen L. Carter at [email protected]

-

Although her name is frequently given today as “Willa,” contemporaneous reports give “Willie.”

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.