Chip Williams, an independent advisor with Raymond James Financial Services, is concerned about the insurance policies his clients are carrying. And he's always been extra careful when it comes to insurance: For the last 40 years he's been reviewing his clients' policies about every two years to make sure they're still the right fit, and on the right track. During those years, he focused primarily on the internal workings of the individual policies. These days though, he's more worried about the carriers of the policies than the policies themselves. “I think about the life insurance company and the holding company it operates under and what financial condition they're in. I think everyone should be paying attention to that now,” Williams says.

Life insurance stocks have taken a hefty beating in the last year, falling nearly 60 percent in the twelve months through April, 2009, according to data from Google finance, compared with a 40 percent drop in the S&P 500 over that period. Insurance giants, such as AIG, Prudential and The Hartford Financial Services Group, have recorded huge losses and are expected to take more. As the value of their investment portfolios drop, many of them have seen their credit ratings downgraded as well, while their regulatory capital needs are going up.

Continuing investment losses, combined with large sums in guaranteed payments due on variable annuity contracts, and substantial exposure to commercial mortgage backed securities, are lingering challenges for many companies in the industry. Suddenly, advisors are becoming a lot more cautious about which insurance companies they do business with. Buying insurance for clients used to be a pretty simple process, says Aite Group senior analyst Doug Dannemiller. “You find the right coverage for clients, you make some money and move on. That's not the case any longer. There should be much more research and effort put into [selecting] the carrier — their stability and performance,” he adds.

Vincent Gianatasio, head of Scarsdale, NY-based Investors Strategy Corporation says he's finding that his clients are asking more questions about insurance companies, too. “The financial stability of an insurance company would always be a part of our proposal, but it wasn't at the forefront of our presentation,” says the Cadaret, Grant-affiliated rep. “Now, it's the second topic clients ask about.” He's found that some clients presented with the proposals are willing to pay a higher premium for a more stable company.

None of this helps Gianatasio's existing clients, of course, who already hold insurance policies. “I got a call from a client [who owns a large number of policies from Lincoln Financial] who had read about the stability of the company. He wanted to know why I'd placed him with Lincoln because they're being clobbered. Well, we'd placed him there four years ago, and four years ago that wasn't a problem,” he says.

Portfolio Wreckage

The cascade of complications insurers face begins with their investment portfolios. Thanks to regulatory restrictions, insurance companies' portfolios — comprised of premiums they collect for life insurance policies and annuities — are typically fairly conservative. Most of the money, about 60 to 80 percent, is invested in highly rated corporate bonds. The remainder is split among treasuries, municipal bonds, real estate, equities, mortgage and other asset backed securities. Obviously, many of these instruments have been performing poorly of late, but it's the corporate bonds that are hurtng the most. “It's not even that corporate bonds have performed so poorly. It's that life insurers are overly exposed to them — they make up such a big chunk of their portfolios — that even a relatively small loss will have a bad effect,” says Alan Rambaldini, an equity analyst at Morningstar.

It could get worse. Eric Berg, a Barclays analyst in New York, says corporate bond defaults will increase “significantly” this year as the recession continues. “None of the life insurers we studied appear to be doing a particularly good job” of picking corporate bonds, Berg wrote in a research note dated Feb. 2. “Understandably, investors are concerned.”

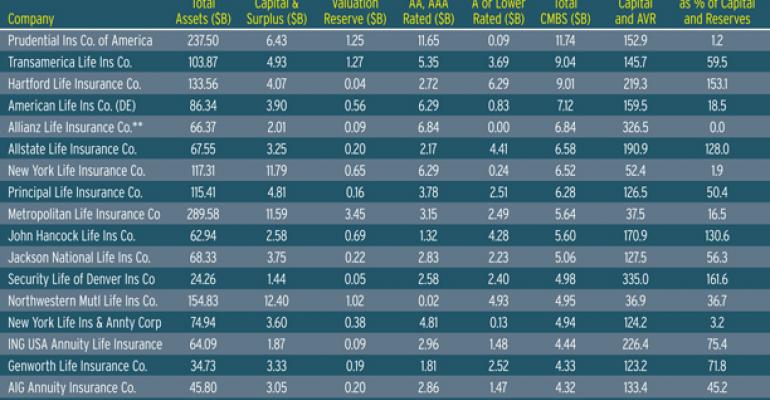

Another big threat to the life insurers' financial stability is the commercial mortgage-backed securities still on their books. Despite numerous writedowns last year, the industry was holding $214 billion in commercial mortgage-backed securities at the end of 2008, according to SNL Financial. At that time, fourteen of the largest life insurers had more commercial mortgage-backed securities than combined capital and reserves. (See chart on page 43 for life insurers with largest exposure to CMBS.) Further downgrades of the insurers' CMBS holdings by credit rating firms could force the firms to make more write-downs. And further downgrades may well be in the cards: Standard & Poor's is expected to make “large scale” ratings cuts on U.S. commercial mortgage-backed securities. At particular risk are “AAA” rated CMBS.

Compounding the problem is the fact that as the value of their investment portfolios fall, and the risks to their balance sheets go up, insurers must increase the regulatory capital they have on hand to cover their obligations. State regulators mandate the level of reserves a company must maintain based on that company's liabilities and risks. “Over the course of this recession, life insurers have had write-downs on their investment portfolios and have had to shore up their reserve cushion at the same time,” says Peter Galanis, president of the National Organization of Life & Health Insurance Guaranty Associations, nolhga. “The deeper and longer the recession gets the more of a challenge it becomes for insurance companies to maintain a healthy level of [capital],” he adds. What's worse, if they don't have the capital on hand, there aren't a lot of places they can go looking for it in this environment, considering the credit squeeze, and their own declining credit ratings.

Variable Annuity Whammy

The other Achilles heel for insurance companies is their variable annuities contracts, particularly those with guaranteed minimum benefits. The decline in insurers' investment portfolios is making it harder for them to meet guaranteed payouts on the contracts. “Variable annuities are the brunt of the problem for life insurers. There's no asset class that's really avoided this market's fall. That's a huge problem for companies that sold a lot of the variable annuities because now they have fewer assets to back them up with,” says Morningstar's Rambaldini.

In the past 10 years, the annuity market has grown more than 50 percent, according to Limra International, an industry research group. But variable-annuity assets lost 13 percent in value to $1.1 trillion during the fourth quarter compared with the third quarter, according to NAVA, which is now called the Association for Insured Retirement Solutions. Analysts say many life insurers put themselves in a vulnerable position over the last few years by offering increasingly aggressive annuity guarantees to investors in order to compete with one another — regardless of how the market performed. Some variable annuities allowed for a 7 percent guaranteed annual payout. (Today, many of the variable annuity issuers are revamping their generous offers for new clients — see story on page 9.) Even as their portfolios lose value, big insurers like Lincoln and MetLife are on the hook for those payments. (See chart on page 44 for largest issuers of variable annuities.)

Now, credit ratings agencies are looking more closely at life insurers that are heavily exposed to variable annuities and whose investment portfolios have taken a big hit. Already, the sector has been the target of numerous downgrades. Hartford Financial Services Group, Lincoln National, MetLife, Protective Life and Prudential Financial are just some of the companies whose ratings have been cut this year. And in 2008, there were 31 downgrades in the life insurance sector, versus just eight upgrades.

TARP To The Rescue?

Last month, the U.S. Treasury Department said some life insurance companies were among firms considered eligible for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). The treasury said it would extend the aid to insurers that own federally chartered banks on a case by case basis. To become eligible for government funds, a number of life insurers made deals to buy savings and loans institutions. Both The Hartford and Lincoln made such acquisitions last November. Companies like MetLife and Prudential already had banking operations. It's not clear how many insurance companies have applied for TARP, but the Treasury says there are hundreds of applications under review.

So do financial advisors need to worry about life insurance companies making good on their clients' contracts? There are certainly a lot of regulatory safety nets in place. State regulators send warnings and demand back up planning as soon as a company's risk-based capital ratio falls below a certain level — 150 percent in some states. If this strategy fails, the insurance department of the state in which the company operates takes over, and that state's insurance commissioner becomes the “receiver.” If the insurer is deemed insolvent, a liquidation may be ordered by a court and state guaranty associations work with the receiver to pay covered claims. Most states provide up to $300,000 in total benefits for any one individual with policies from an insolvent insurer, according to the NAIC.

But these payments are financed by state guaranty funds, which are backed by the insurance companies themselves, and the companies don't typically kick in payments until an insolvency occurs. “If a company goes down, a fee is levied on the remaining companies in that state to shore up the fund. Right now though, there aren't a lot of life insurers in the position to put up cash,” Rambaldini says. Multiple simultaneous insolvencies would be a disaster.

Of course, nolgha says it doesn't expect a major increase in insurance insolvencies. There have been two this year, and according to a spokesperson for the group, that's normal. “Regulators have gotten much better at preventing insolvencies. They focus on warning signs so they can get in there earlier when their options for recovery are broader,” says Galanis. And anyway, if an insurer does go bust, “Policy holders have to get taken care of first. They're first in line when an insurer goes under,” says Galanis

Joseph Belth, an insurance expert and retired Indiana University professor, says the threats to the life insurance industry may be overstated. Citi's Devine agrees: “There are plenty of financial institutions fairing much worse than insurers. Life insurance companies are not in medical triage.”