By Heejin Kim and Tom Redmond

(Bloomberg) --As many hedge funds suffer from a prolonged bout of weak returns, one New York money manager says he’s found an antidote on the other side of the world.

For Andrew Tsai, chief investment officer of the $750 million Chalkstream Capital Group, the answer is 6,800 miles (10,900 kilometers) away in South Korea. With the cheapest stocks in major Asian markets, a legion of day traders whipping prices around, and fewer sophisticated institutional investors to take advantage, it’s like returning to the golden era for generating alpha, or benchmark-beating performance, he says.

“Quite simply, it’s an overlooked country,” Tsai, 45, said in a phone interview. “If I could go back in time to the U.S. equity markets in the late ’80s and understand all the ways that hedge funds made money and kind of do it again, I feel that Korea is that same opportunity.”

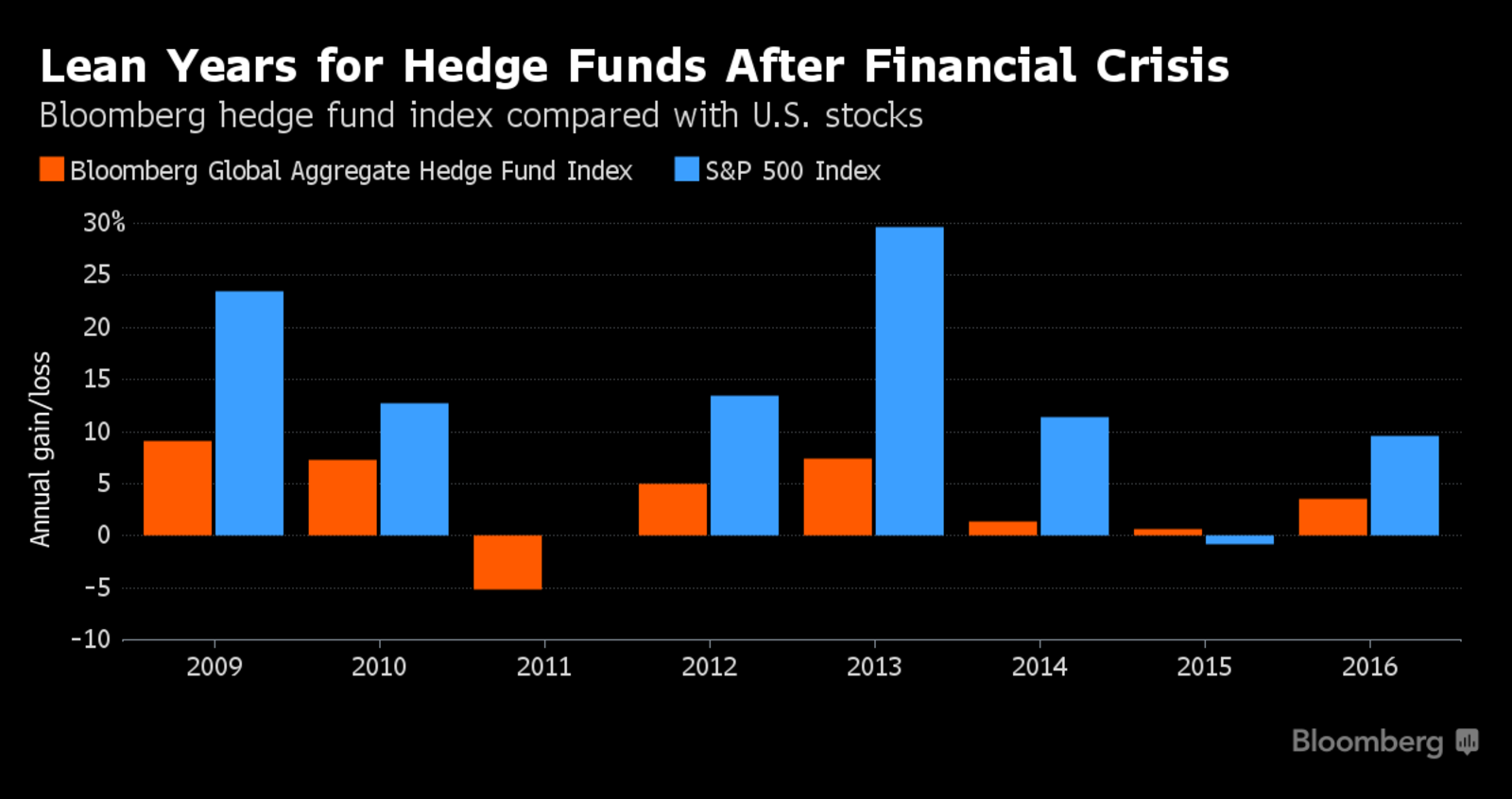

Hedge funds are seeking new ways to stand out as the $3 trillion global industry reels from poor performance and big redemptions. Last year, the average fund delivered less than half the return of the S&P 500 Index of U.S. stocks. For Tsai, that’s partly because the business has become so crowded. “If everyone has the same edge, by definition” alpha isn’t going to be there, he says.

Chalkstream started as a family office in 2003 to manage the money of co-founder Peter Muller, the mathematics whiz and singer-songwriter who runs the quantitative hedge fund PDT Partners, which spun off from Morgan Stanley. The next year, Chalkstream opened to outside investors.

As well as managing hedge funds, Chalkstream invests in private equity and real estate. While the company has holdings in companies across the world from Brazil to Israel, Tsai says South Korea, where his company works with local investment partners that he declines to identify, is tied for its largest allocation. Chalkstream also stepped up investments in Japan in 2012, just before the rally ignited by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s policies to revive the economy and spur inflation.

Tsai, who started his career as a bond trader at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in the early 1990s and also had his own hedge fund before joining Chalkstream, says his team visited Seoul more than 20 times in the past four years. He says foreigners ignore the market because of the threat of North Korea and concerns about corporate governance.

“We hosted a symposium in New York dedicated to Korean hedge fund strategies in 2015,” Tsai said. “In a room of over 100 institutional investors that travel the world actively for investments, only a few of them had traveled to South Korea for a business trip to look for opportunities.”

In fact, foreigners accounted for just 30 percent of trading on the benchmark Kospi index last year, and less than 6 percent for the Kosdaq index of smaller shares. Local individuals, meanwhile, are responsible for half of Kospi trading and almost 90 percent on the Kosdaq. This, along with the lack of sophisticated competitors -- Korean hedge funds manage less than $7 billion -- is good news for Tsai.

“Retail investors generally take things too far on the upside and too far on the downside,” he says. “There is quite a lot of opportunity for disciplined long and short investors.”

Then there’s price. The Kospi’s 765 companies on average trade at less than book value, the cheapest in any major Asian market by that measure. Across key developed and emerging countries in the region tracked by Bloomberg, only Mongolia is less expensive.

And there’s what’s known as stock dispersion -- investor lingo for the ability of stock prices to chart an independent course. South Korea has one of the highest levels of this in Asia, according to Lee Jung Ho, an analyst at Yuanta Securities Korea Co. Hedge fund managers see it as necessary for making winning bets.

“Last year, the Kospi was up 3 percent, but if you look underneath the surface, there were almost a third of the stocks in the index up or down over 30 percent,” Tsai says. “That’s how hedge funds made so much money in the U.S. in the early days. It’s by idiosyncratic, company-specific analysis.”

Even the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye and arrest of Samsung heir-apparent Jay Y. Lee in an influence-peddling and corruption scandal are reasons for optimism for Tsai. The turmoil last year is positive for stocks, he says.

“There is a referendum on the way things have been done in Korea, at the government level and at the corporate level,” Tsai says. “Things are changing pretty quickly,” he says. “That could spell some good things for corporate governance.”

Last year was a tough time for hedge funds globally, and in South Korea. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Hedge Fund Index rose 3.6 percent in 2016, against a 9.5 percent gain for the S&P 500. The average South Korean hedge fund added 1.2 percent.

Tsai declined to give details on Chalkstream’s returns, citing regulatory restrictions. But as the clamor grows for hedge funds to justify their fees, he has high hopes for his South Korean investments.

“Alpha doesn’t come all at once,” he said. “It is chunky. And a lot of the things that happened last year, we think, are setting up for an extremely attractive alpha environment.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Heejin Kim in Seoul at [email protected] ;Tom Redmond in Tokyo at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sree Vidya Bhaktavatsalam at [email protected] ;Divya Balji at [email protected] Tom Redmond